Today is Armistice Day. In America, we refer to it as Veteran’s Day and honor the living. We have since 1954. After World War II (1939-1945) and the Korean War (1950-1953), it was difficult for Americans to honor veterans only from one war. However, many in Europe still continue with their flavor of Armistice Day that began with the armistice of World War I (1914-1918).

Regardless, this marks the 93rd anniversary of the day Europe ceased fire during the Great War. In a conflict that claimed nearly 15 million soldiers killed in action and civilians caught in the crossfire, it is impossible for a region to forget its impact. In America, it is a different story. There are no more living veterans. That leaves its designated day of remembrance for Memorial Day, which has stiff competition from “deadlier” wars and recent conflicts. As such, this story seeks to bring back some remembrance to World War I, a war that claimed more than 120,000 American lives.

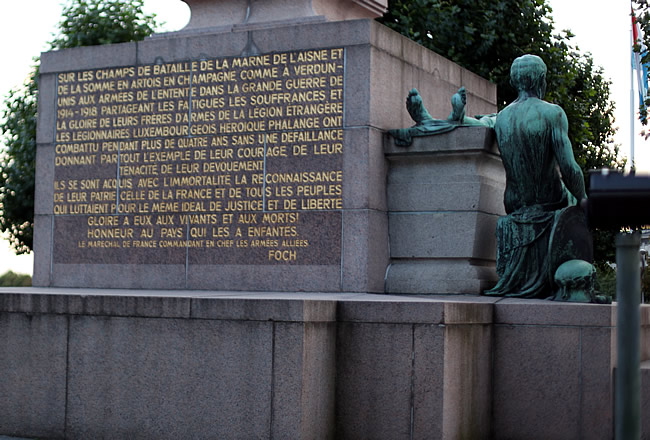

Luxembourg’s World War I Monument

Luxembourg is a fascinating place. Not only is it the last Grand Duchy in the world, ruled by a grand duke, but the area is several hundred square miles smaller than Rhode Island. Like Belgium, its northern neighbor, it acts as a buffer between northern France and Germany, albeit a small one. As such, the small duchy was in the path of invading Germans in both world wars. Twice, the Luxembourgish were neutral until war was upon their doorstep.

When I visited Luxembourg this past summer on business, I was hot off the trail of the Scottish Highlands where I saw countless World War I monuments. Anxious to see how other European countries commemorated the war, I kept my eyes open among the statues and older buildings. While in a busy street market, I saw an old postcard, which featured a black and white photo of a female statue holding a wreath, sporting the title “Monument de Souvenir.” I showed the postcard to a coworker and said, “Take me here!” I was not positive that it was a World War I monument, but I had a good feeling about it.

As we approached, I saw a large block of French text, which I could not translate at first glance. However, it was signed by Foch. With that name, Marshal Ferdinand Foch, the general who led the French army in the final year of the war, I knew we had found it.

With a rough translation from French, the monument mentions the “Luxembourgish heroic phalanx” that fought in several battles including the Marne, Somme, Champagne, and Verdun. They fought for over four years to give all and provided an example with their courage, tenacity, and dedication. France recognized their struggle for justice and freedom. Glory to those alive and dead. Then the monument attributes the quote to the Marshal of France, Commander in Chief of the Allied Forces, Foch.

The mention of the phalanx matches the base of the monument, which features a Spartan warrior mourning a fallen soldier.

Luxembourg originally erected the monument in 1923 to commemorate World War I. After the Germans invaded again in May 1940, the occupiers tore it down in October. The Germans saw the monument as a symbol of resistance and by tearing it down, they transformed that fear into reality. When the Luxembourgish re-erected the monument in 1950s, they expanded its meaning to include those who fought in World War II and the Korean War.

On the left side of the monument is a 1945 quote from Grand Duchess Charlotte (r. 1919-1964). Roughly translated, the Duchess says she is proud of the Luxembourgish who followed the example of their elders and joined the Allied Army to defend the cause of their country. She bows to the victims and heroes of the country and the mourning of their families. Their blood had not been in vain. By their death, there is a real homeland of Luxembourg.

Then, of course, there is the breathtaking Golden Lady at the top.

Although a small duchy, Luxembourg is but a slice of Europe, a region that suffered terribly during the world wars. Monuments like these are overwhelmingly powerful to visitors like me who cannot help but take notice of the Spartan warriors, Foch’s name, and the Golden Lady high above the ground. The monument is also successful, as it has me talking about World War I, nearly 90 years after it was built.