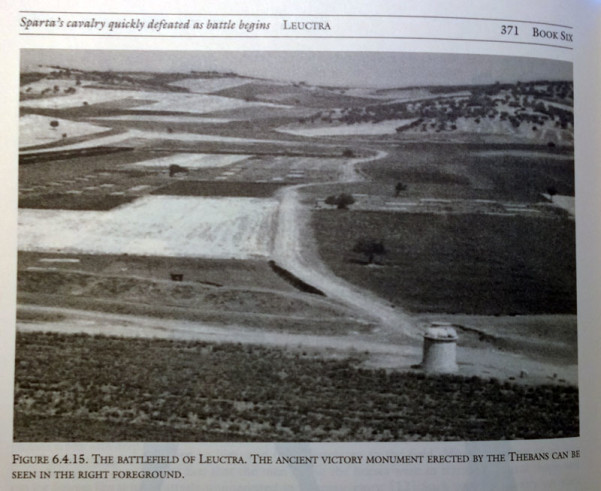

I remember the exact moment when I decided to go to Greece. I was flipping through my copy of the Landmark Xenophon when I came across a blurry black and white photo of the Leuctra Victory Monument, celebrating the Theban and Boeotian victory over the Spartans in 371 BC. This battle was important for many reasons, mainly because it marked the end of Spartan dominance in Greece and even saw the death of King Cleombrotus, the first Spartan king to die in battle since Leonidas (480 BC).

This lonely, dome-shaped monument was the dwarfed by the large, open field, yet it remained a peculiar feature of the landscape.

It fascinated me. I had to see it. I had to pay tribute.

As with most Greek monuments discovered in the 19th- and early 20th-centuries, the Greeks restored it.

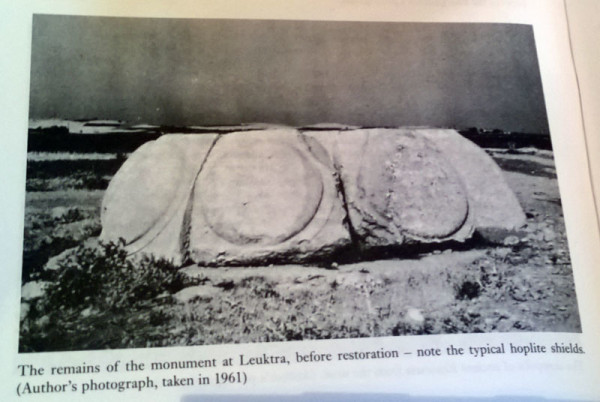

As I prepped for the trip, I learned how the monument was a modern interpretation mixed with ancient fragments, the first of which German classicist H. N. Ulrichs discovered in 1839. ((W. Kendrick Pritchett, Studies in Ancient Greek Topography, vol. 1 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1956), 51.))

Yet, it was not until the 1920s that Greek architect-turned-archeologist Anastasios Orlandos started studying the pieces in earnest, eventually restoring the monument in the 1960s. ((Jutta Stroszeck, “Greek Trophy Monuments,” in Myth and Symbol II: Symbolic Phenomena in Ancient Greek Culture, ed. Synnøve des Bouvrie (Norway: The Norwegian Institute at Athens, 2004), 307, 321.))

A photo taken during the restoration effort reveals how unimpressive it was initially. ((Photo from J. F. Lazenby, The Spartan Army (Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books, 2012), plate.)) A circular formation of nine Greek shields, each measuring 3.2 ft in diameter, created a dome-like feature. ((Diameter of shields in J. K. Anderson, Military Theory & Practice in the Age of Xenophon (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1970), 17.)) Together, the shields measured just shy of 12 ft in diameter. ((Stroszeck 2004, 307, 321.))

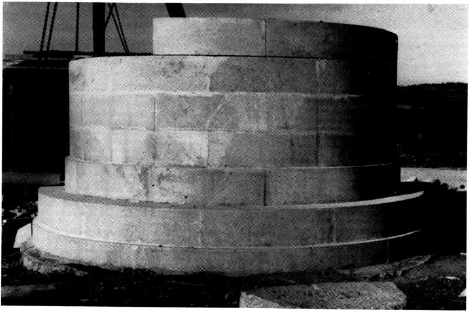

Orlandos toiled to restore the monument to its previous glory, but no one was sure what that glory looked like. The discovery of a single panel led Orlandos to believe that the dome top rested upon an elevated foundation, thus the creation of a cylinder base. ((Photo of cylinder base in progress from George Daux, “Chronique deFouilles, 1960,” Bulletin de Correspondence Hellénique 85 (1961): 743.)) He relied on the diameter to determine the appropriate height proportionately to what the builders had originally constructed. ((Stroszeck 2004, 321.))

Although Orlandos was ultimately guessing, his architectural background adds some credibility to the results, which are impressive. To the uneducated modern-eye, the monument appears to be a remarkable ancient structure. The Leuctra Victory monument, however, is a 20th-century creation, not an ancient one.

Notice the panel under the dome that looks like it was shoved in the monument. This is the original ancient panel that help Orlandos determine the height of the base.

Scott Manning for scale.

But what was on top of the monument?

Regardless of what the ancient monument looked like in all its original glory, it was not the first to commemorate the Battle of Leuctra. While Xenophon, the only contemporary historian, described the building of a trophy immediately after the battle and before the Spartans were allowed to collect their dead (Hell., 6.4.15), the trophy was most likely a makeshift one made from captured arms and armour attached to a stake. ((Hans van Wees, Greek Warfare: Myths and Realities (London: Duckworth, 2004), 136.))

The fragmented monument we see today was constructed well after the battle and it included a bronze statue on top, now lost to history. Cicero was so offended by such a permanent structure that he emphasized the temporary nature of war trophies, which were meant to be remembered “for the present” and “not remain forever” (Cic., Inv., 2.23.69). ((Translation from William C. West III, “The Trophies of the Persian Wars,” Classical Philology 64, no. 1 (1969): 10-11.))

In addition, ancient historians such as Diodorus stated explicitly that the temporary nature of battle monuments was the custom of victorious Greek armies (13.24.5).

Luckily for us, the Boeotians did not stop an offending bronze statue, as coins still exist from the region, sporting the bronze trophy of a soldier. ((Stroszeck 2004, 305, 311, 321; Andreas Jozef Janssen, Het Antike Tropaion (Brussel: Paleis der Academiën, 1957), 61.))

One such coin features the goddess Athena on the other side. More impressive, it was available on eBay last year for a mere 30 bucks.

As coins can be difficult to photograph, an outline sketch of the side bearing the soldier reveals what the trophy on top of the Leuctra monument may have looked like.

It is clear that the bronze soldier sported a helmet, shield, sword, and spear. With this bronze statue on top of the dome of the Leuctra Victory monument, it would have dominated the relatively flat landscape.

No wonder Cicero was so offended several hundred years later. In the 21st-century, the mere remnants of it sent me to Greece.