Resting on a hill above the town of Distomo, Greece, is a massive memorial and ossuary. It contains the names and skulls of victims from a 1944 German massacre in this town where 218 men, women, and children were slaughtered. ((Stephanie Bird, et. al., eds., Reverberations of Nazi Violence in Germany and Beyond: Disturbing Pasts (London: Bloomsbury, 2016), 1.))

How we even know the details of June 10, 1944 is remarkable. In response to an ambush that happened several miles outside Distomo, a Waffen-SS unit, knowing full well the perpetrators were not in the town, entered Distomo and massacred its citizens. Survivors later testified to rape, pillaging, and wild shooting at everyone. ((Mark Mazower, Inside Hitler’s Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941-44 (New Haven: Yale University, 1995), 212-215.))

There is at least one surviving photo of German troops standing by while the town burned.

We are so sure of this account, because the Germans investigated the incident after reviewing conflicting reports—one from the Waffen-SS commander who described mortars and machine gun fire coming from Distomo and another from a German police agent who described otherwise. During the inquiry, the Waffen-SS commander admitted to fudging his official report. He explained that

mindful of those killed and wounded in my company I consciously made the decision to follow the spirit rather than the letter of the orders governing reprisals. I was aware that my orders could be construed as formal insubordination, but expected that they would be retrospectively approved on soldierly and humane principles. ((Mark Mazower, Inside Hitler’s Greece, 212.))

The commander further argued that the people of Distomo surely knew of the ambush and would likely contribute to another. His attack on the town was therefore necessary. The tribunal concluded as much, even going so far to proclaim that “non-use of arms would have led to proceedings for negligent release of prisoners.” ((Mark Mazower, Inside Hitler’s Greece, 212, 214.))

The testimonies, documents, and bodies left plenty for the Greeks to remember after World War II. They eventually built this monument in the 1980s, which is overwhelming in its size and imagery. When you finally get on the platform atop the hill, the monument has an open design, which makes it feel even larger.

There are images of forced marches, women crying, and even one German troop makes an appearance in a surreal display. On one panel, an old woman is resigned while a mother clutches her baby. The man of the family is standing up in a lost cause to prevent the inevitable.

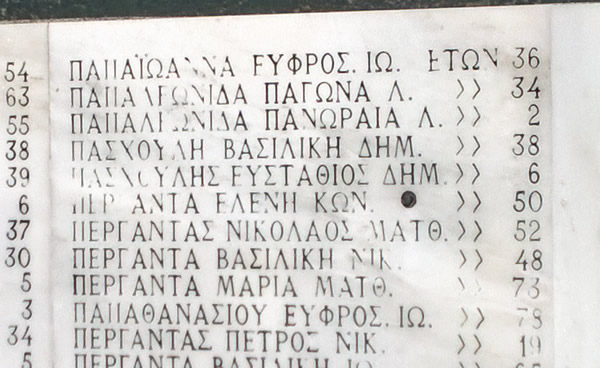

Also overwhelming are the names and ages of the victims from the massacre in alphabetical order.

Even if you can’t read Greek, you can recognize the numbers next to each name, covering a wide range—36, 34, 2, 38, 6, 50, 52, 48, 73, 78, 19, and so on. The victims cover every age bracket.

Then there was the chapel and ossuary containing skulls of some of the victims.

We did not have the opportunity to visit inside the chapel or the ossuary, but perhaps it was best we let these Greeks rest in peace.

The Greeks hold commemorations here every June 10.