In May of 1958, the People’s Republic of China launched The Great Leap Forward, an effort by the country’s leaders to transform China into a military superpower in just five years. The goal was to increase the country’s grain and cereal production by grouping the peasants into “thousands or even tens of thousands of families, with everything to become communical. . .” ((Stephane Courtois et al., The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999), 488.)) The peasants would work longer and harder while practicing extreme frugality. The result was a great jump backward when about “38 million people died of starvation and overwork” in the ensuing famine that followed. ((Jung Chang and Jon Halliday, Mao: The Unknown Story (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 438.)) There are many causes of such an astronomical body count, but they can be grouped into four major categories: ignorance, fear, denial, and apathy. The Communist Government is the main culprit in this mass death because it was ignorant in its lofty goal-setting for grain production, it scared the peasants and local leaders into inflating their statistics, it denied reports of starvation and missed goals, and it ultimately did not care that people would die in the process of taking a “great leap forward.”

The leader of Communist China, Chairman Mao Tse-Tung, was the brainchild of the Great Leap Forward. In 1958, the government propaganda told the people “that the goal of the Leap was for China to ‘overtake all capitalist countries in a fairly short time, and become one of the richest, most advanced and powerful countries in the world.'” ((Chang and Halliday 2005, 426.)) In order to accomplish this goal, the nation would be required to increase production in its main commodity: grain. A goal of 375 million tons of grain was set for the year 1958. ((Jonathan D. Spence, The Search for Modern China, 2nd ed. (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1999), 550.)) This was almost twice the actual production of 195 million tons in 1957. ((Courtois et al. 1999, 488.)) The problem was Mao “calculated on the basis, not of what the peasants could afford, but of what was needed for Mao’s Programme.” ((Chang and Halliday 2005, 426.)) Mao’s Programme was militaristic in nature. In 1958, Mao told a group of military officers that the “Pacific Ocean is not peaceful. It can only be peaceful when we take it over.” ((Chang and Halliday 2005, 426.))

At first, local leaders claimed they were meeting the lofty goals when in reality they weren’t even close. The actual amount of grain produced for 1958 was 215 million tons ((Spence 1999, 550.)) which was nearly 52% less than what was estimated and reported. “Cowed by the mass rural hunts for dissidents, and manipulated by their local political leaders who were often fighting their own career battles, local peasants dared not dispute even the most fanciful claims for higher agricultural yields.” ((Spence 1999, 548.)) A vicious cycle began. Local leaders continued to give false reports of meeting impossible goals and other local leaders followed suit in order to keep pace. The Communist Government appropriated grain for its needs as though the goals were met while the peasants went without food. One such need was used to produce ethyl alcohol for fuel in “missile tests, each of which consumed 10 million kilograms of grain, enough to radically deplete the food intake of 1-2 million people for a whole year.” ((Chang and Halliday 2005, 429.)) Another use was to export the grain for money and other military projects in which millions of tons were exported. ((Courtois et al. 1999, 495.))

Reports of the food situation and missed goals did trickle into the government, but they were ignored. In April of 1959, a series of reports were shown to Chairman Mao stating that “there was severe starvation in half of the country. . .” and “his response was to ask the provinces to ‘deal with it.'” ((Chang and Halliday 2005, 428.)) In July of the same year, Mao received a report from an army marshal who called into question the 375 million tons of grain reportedly produced from the previous year. The report was sent privately to Mao whose response was to circulate “it to all the senior cadres . . . and launched a personal denunciation [of the army marshal].” ((Spence 1999, 551.))

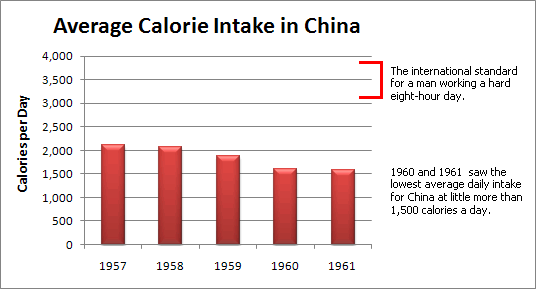

In 1960, the Communist Government estimated that the “average daily calorie intake fell to 1,534.8.” ((Chang and Halliday 2005, 437.)) This is less half the estimated 3,100-3,900 calorie/day international standard needed by a man working a hard eight-hour day. ((R. J. Rummel, China’s Bloody Century: Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1900 (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1991), 250.)) Before the Great Leap Forward began, China did not have enough food to feed the population and the Communist Government knew it. In January of 1958, a government meeting concluded that there was not enough food to eat. Mao gave the following solution: “No worse than eat less . . . Oriental style . . . It’s good for health . . . I think it is good to eat less. What’s the point of eating a lot and growing a big stomach, like the foreign capitalists in cartoons?” ((Chang and Halliday 2005, 427.)) These were the same capitalists that Mao was determined to overtake with the Great Leap Forward. A year earlier Mao stated, “We are prepared to sacrifice 300 million Chinese for the victory of the world revolution.” ((Chang and Halliday 2005, 439.))

The Great Leap Forward produced the greatest famine in human history. The Communist Government set impossible goals for grain production based off of military needs. In order to meet these goals, the people worked harder and lied about their actual production. When the reports about starvation throughout the country were received, they were ignored. The government knew from the beginning that the country was already dangerously low in food production, but proceeded with the plan anyway. Mao gambled for supremacy in the world and the cost was 38 million people, but this was only one tenth of what he was willing to sacrifice for “the victory of the world revolution.” ((Chang and Halliday 2005, 439.)) The world revolution never came, but people of China still paid the price.

Bibliography

Chang, Jung, and Jon Halliday. Mao: The Unknown Story. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005.

Courtois, Stephane et al. The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Rummel, R. J. China’s Bloody Century: Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1900. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1991.

Spence, Jonathan D. The Search for Modern China. 2nd ed. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1999.