One of the most difficult aspects of reading military history is the brutality of it all. Some accounts are so detached, so transactional that it hardly makes a blip on the humanity scale. When Arrian described Alexander’s troops massacring Greek mercenaries within the Persian army at Issus, he simply described them as “cut off” and “decimated by the phalanx.” ((Arrian, 2.11.2. This translation comes from the Pamela Mensch translation (New York: Pantheon Books, 2010).)) Sympathizing with these men requires a lot of imagination.

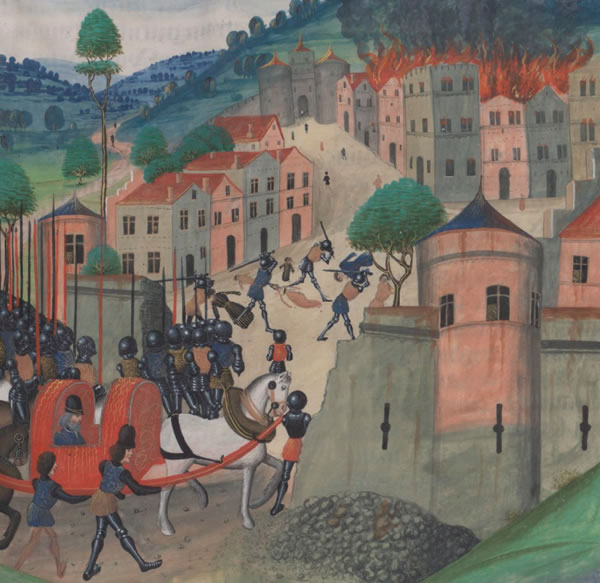

Other accounts stay with you. When the French chronicler Jean Froissart (c. 1337-1405) described the Black Prince’s siege of Limoges, he was clearly emotional in the aftermath. After a lengthy siege that only ended through an assault, the English stormed the city. The civilians tried to flee, but the pillagers were “all in a mood to wreak havoc and do murder, killing indiscriminately.” ((All quotes from Froissart come from Jean Froissart: Chronicles, translated by Geoffrey Brerton (New York: Penguin, 1978), 178.))

Why? Froissart tells us that those were their orders.

There “were pitiful scenes,” as “men, women and children flung themselves on their knees before the Prince,” crying for mercy.

Then it gets bad.

But [the Prince] was so inflamed with anger that he would not listen. Neither man nor woman was heeded, but all who could be found were put to the sword, including many were in no way to blame.

Froissart continued with the gruesome detail of how the pillagers dragged out more than 3,000 men, women, and children in order “to have their throats cut.” His editorializing strikes a chord with our modern sensibilities. He did “not understand how [the pillagers] could have failed to take pity on people who were too unimportant,” meaning they were merely civilians and not in charge of defending the city against the siege. Froissart believed that no man or even God “would not have wept bitterly at the fearful slaughter which took place.”

One of the more remarkable (or horrifying!) aspects was how neither gender nor age gave any advantage for survival among the civilians in Limoges.

Now here comes the real hard part—this was typical of medieval sieges.

As historian Jim Bradbury points out, “If one condemns the Black Prince, then one condemns virtually all medieval siege commanders.” ((Jim Bradbury, The Medieval Siege (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 1992), 161.)) Instead, Bradbury believes it was likely Froissart’s French sensibilities getting the best of him during his narrative. Not only did he editorialize, but he possibly exaggerated the brutality. ((Jim Bradbury, The Medieval Siege (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 1992), 166, 318.)) Historian David Green makes a similar point and adds that “the lack of comment from local chroniclers implies the sack was not unusually savage.” ((David Green, The Hundred Years War: A People’s History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 55.))

Still, sitting here reading Froissart’s account 646 years later, I am not weeping bitterly, but I am cringing with the thought of it all. I have read countless descriptions of sieges, but this one will stick with me.