In addition to the Dying Gaul being a remarkable piece from antiquity, the restorations of it have become part of its rich history. Originally excavated around 1620, it saw several restorations immediately afterward. While the piece seems complete now, it was missing its right arm, left knee, toes, left thumb, nose, penis, and portions of the base including the sword. All of that was restored over a 5-year period, along with several polishes that removed any ancient coating, forever changing the original state of the piece.

Yet the restoration is so old now that it is itself historic. Consider that this 1800-year-old Roman copy of a 2200-year-old Hellenistic original came to its current state through “restorations” from nearly 400 years ago.

Here is a closer look at those restorations.

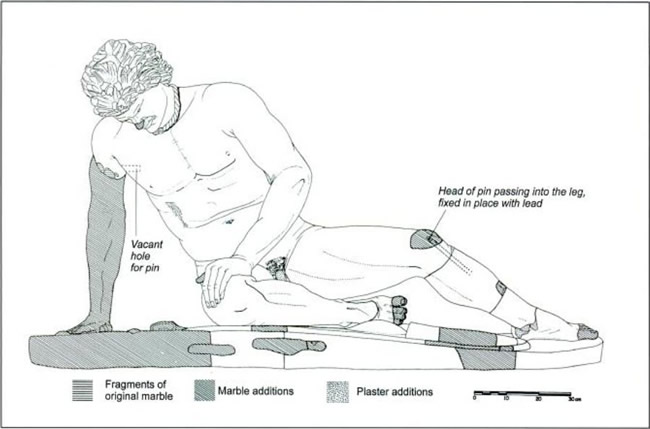

On first glance, most viewers will miss the restorations. For example, I viewed the piece with two others and we had no clue. Yet if you know what to look for, then the restorations are very apparent. ((This sketch comes from Giovanna Martellotti, “Reconstructive Restorations of Roman Sculptures,” in History of Restoration of Ancient Stone Sculptures, eds. Janet Burnett Grossman, Jerry Podany, and Marion True (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2003), 180.))

First, consider the right arm, which was completely replaced. You can see a clear line above the bicep and triceps where the added arm connects.

Likewise, the left knee was added and conceals a rod that runs through the lower half of the leg to hold together four larger pieces.

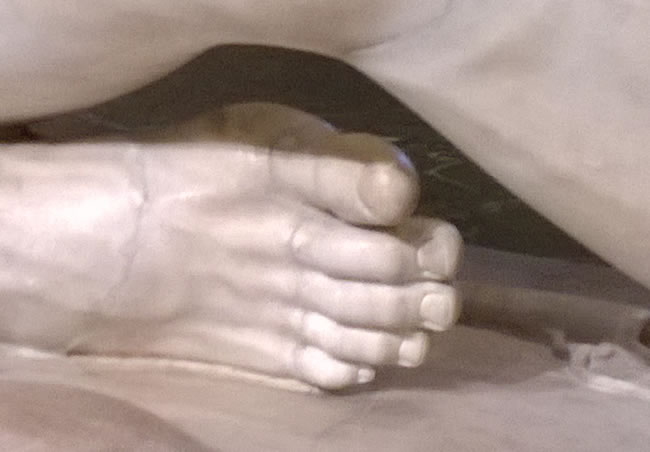

All of the toes were missing as well.

As was the left thumb.

The base where the Gaul rests his right arm was added during restoration as well, including the sword.

You can see where the restorer pieced the original base to its addition.

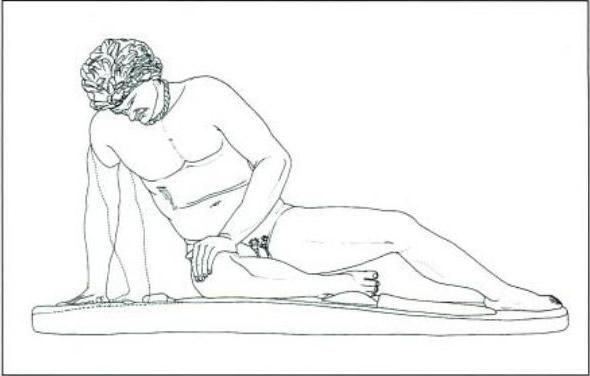

Again, unless someone points it out to you, you would likely never catch the restorations. It is not flawless though. The added right arm is 3-5 cm shorter than the left arm. ((Martellotti, 181)) Giovanna Martellotti believes this changes the interpretation, as the restored arm gives the impression that the Gaul is resisting death whereas a shorter arm angled more closely to the body would have resembled more of an action scene, of a man falling from a wound (see below). ((Martellotti, 182))

While there are plenty of horror stories of restorations gone wrong, they are not all bad. In the case of the Dying Gaul, the piece appears more complete, likely attracting more spectators. In addition, the restorations are now themselves historic, older than any monument in the United States. By understanding what was restored, we can appreciate both the Roman and Renaissance interpretations of the Dying Gaul.

If you are interested in learning more about restorations to the Dying Gaul and other ancient sculpture, then History of Restoration of Ancient Stone Sculptures is worth checking out.