Justin Kelly and Mike Brennan have produced a convincing monograph on the need to reign in the influence of operational art in American war planning and execution (Alien: How Operational Art Devoured Strategy). In it, they trace the evolution of the term from the industrial period, as it gained prominence in the Soviet and German armies after World War I. Today, it has become a barrier in between strategy and tactics, especially in American wars.

Most interesting was how the term and its current meaning came into the English-speaking world during the 1980s. I had thought the concept was older than that, but never gave it much thought until now. When I started my degree in military history, one of the first tenants I learned was that there are three distinct levels of war—strategy, operational art, and tactics. Strategy, the highest level, represents the political goals of the state orchestrated by the leaders. Operational art sits below strategy and focuses on executing tactics in order to achieve the political goals. Finally, tactics are the battles, the fighting. In many of my courses, teachers have stressed the need to identify which of the three levels I was operating in when analyzing any battle or war.

Yet, until the past few hundred years, there was not a strong need for anything resembling operational art. In ancient Greece, political leaders were often synonymous with generals. In the medieval world, state leaders often campaigned with their armies. Consider English King Edward I (r. 1239-1307), as he conquered Wales and Scotland, or Genghis Khan (r. 1206-1227), as he conquered China. In modern warfare, Kelly and Brennan use the examples of Prussian King Frederick the Great (r. 1740-1786) and Emperor Napoleon (r. 1804-1815) campaigning with their armies (p. 11). Thus, a state’s leader could determine on the field if a campaign or battle was worth the cost to achieve his political objectives. These leaders could give input to or even direct the tactics firsthand. Yet, as armies and battlefields became bigger and the roles of political leader and military leader separated, there arose a stronger need to translate strategy—the political objectives—to the battlefield.

So what is the big deal? I already used the term “barrier” to describe operational art. Kelly and Brennan’s source of contention comes from the definition from an army manual, which defines operational art as “the employment of military forces to attain strategic goals in a theater through the design, organization, and conduct of campaigns and major operations” (pp. 61-62). The use of the word “design” gives this middle tier direct control over campaigning and tactics. The result is operational art has morphed into an ambiguous role, as it often overtakes strategy in campaign planning, excluding politicians once they have determined their high-level objectives. Abstractly, many Americans would support the concept of a president defining a warpath and letting the generals loose to accomplish the mission as they see fit, but this is explicitly what Kelly and Brennan argue against (p. 94). History is ripe with examples (recent ones!) where this approach—politicians setting strategy and remaining disconnected from operational art and tactics—yielded poor results for a state.

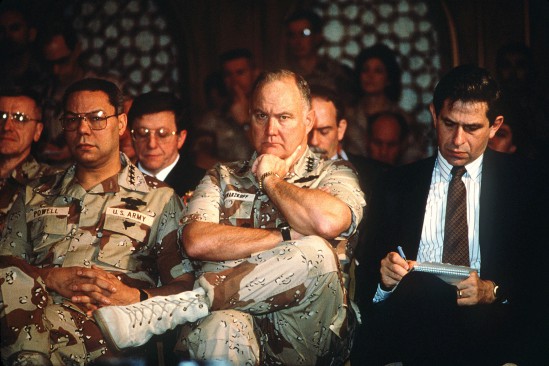

The easiest example, which the authors’ mention briefly, is the Persian Gulf War (1990-1991). President George H. W. Bush set his political objectives and allowed his generals to do all the campaign planning. However, the political leaders did not incorporate politics into the campaign or tactics sufficiently to achieve a true end to the war. As Kelly and Brennan point out, “the operation supplanted the campaign which, in turn, became the strategy” (p. 69). After the hostilities ended, President Bush relied on General Norman Schwarzkopf to finalize the details of the ceasefire, which allowed Saddam Hussein to regain control of rebelling regions. The President stated on several occasions that he wanted to see Saddam removed from power, but he was not willing (or able) to incorporate this political objective into the campaigns and tactics of the war. Ultimately, the war with Iraq continued throughout the 1990s, as the U.S. and other allies bombed the country and defended no-fly zones. The war erupted in earnest again in 2003.

Next, we will look at how President Barack Obama has reigned in operational art.