Editor’s Note: This article is part of a larger project detailing the death toll inflicted by Nazi Germany outside the realm of combat. To see the full body count by country click here.

Body Count: 12,250,000 ((This number is determined by taking all available estimates from various sources, averaging them, and selecting the mid-value of the low and high estimates. The low estimate is 8,678,000 and the high estimate is 19,985,000. R. J. Rummel, Democide: Nazi Genocide and Mass Murder (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1992), 131.))

Occupation Death Rate: 18.85% ((This number is determined by dividing the body count by the total USSR population controlled by Nazi Germany in 1942. Population estimate is 65,000,000, which is taken from Leonid D. Grenkevich and Josef Washington Hall, The Soviet Partisan Movement 1941-1945: A Critical Historiographical Analysis (Portland: Frank Class, 1999), 98.))

Deaths caused between 1941-1945

The non-battle deaths of USSR citizens caused by Nazi Germany is by far the highest of any nation that Germany attacked in the Second World War. With a mid-estimate of 12,250,000 killed, this is more than twice that of Poland’s body count. This is more than the entire population of most countries today such as Greece, Belgium, or the Czech Republic. ((At the time this article was written, there were 167 countries with a population less than 12,500,000 million. Greece, Belgium, and the Czech Republic were 10,737,428, 10,414,336, and 10,414,336 respectively. “Country Comparison: Population,” Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook, (22 June 2009).)) In the overall count, the people of the USSR make up over half the death toll.

To understand how this devastation came about, the evolution of Adolf Hitler’s mindset and aims toward Russia must be examined.

Hitler’s Statements in Mein Kampf, 1925

Hitler’s designs for Russian territory were made public before he was ever in power. In Mein Kampf, he referred to Russia as the “Persian empire ripe for collapse.” ((Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, trans., Ralph Menheim (Boston: Mariner Books, 1999), 655.)) The goal of the Nazis was to

. . . bring our own people to such political insight that they will not see their goal for the future in the breath-taking sensation of a new Alexander’s conquest, but in the industrious work of the German plow, to which the sword need only give soil. ((Hitler 1999, 655.))

The reason for such a conquest was to accomplish what Hitler saw as the highest aim of his foreign policy: “to secure for the German people the land and soil to which they are entitled on this earth.” ((Hitler 1999, 652.)) As Hitler saw it, Germany was not a world power until it had the adequate land mass to make it such a power. Land expansion was also necessary for survival. He believed that “only an adequately large space on this earth assures a nation of freedom of existence.” ((Hitler 1999, 643.)) Hitler was not content with the pre-World War I territory and he wanted to move away from the concept of colonization. Instead, he wanted to expand the size of the “mother country.” The land would come from the east. “If we speak of soil in Europe today, we can primary have in mind only Russia and her vassal border states.” ((Hitler 1999, 654.)) To Hitler, Russia was comprised of an “inferior race” ((Hitler 1999, 654.)) and ruled by the Jew. The combination of Jews and communism was too much for Hitler: “In Russian Bolshevism we must see the attempt undertaken by the Jews in the twentieth century to achieve world domination.” ((Hitler 1999, 661.))

As early as 1925, Hitler saw Russia as a land of subhumans that was ripe for conquest.

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

However, this objective appeared to fall to wayside when Germany and the USSR signed a non-aggression pact. In August 1939, the two countries determined to settle any disputes “exclusively through friendly exchange of opinion or, if necessary, through the establishment of arbitration commissions.” ((Article V of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Raymond James Sontag, ed. and James Stuart Beddie, ed. Nazi-Soviet Relations, 1939-1941: Documents from the Archives of the German Foreign Office (Washington D.C.: Department of State, 1948), 77.)) Ten days prior to signing the pact, the German Foreign Minister told the Soviet Union’s Ambassador that there existed “no real conflicts of interest between Germany and the U.S.S.R. The living spaces of Germany and the U.S.S.R. touch each other, but in their natural requirements they do not conflict.” ((Telegram sent from Ribbentrop to Schulenburg. Sontag 1948, 50.))

The pact was broken less than two years later.

Hitler Attacks Stalin

On July 21, 1941, the day before Germany attacked Russia, Hitler sent a letter to his principal ally, Benito Mussolini, explaining that the UK was defeated, but held onto the hope that the Soviet Union would eventually join the war. He reasoned that eliminating Russia would force the UK to give up, relieve pressure off of Japan who could then intervene in American activities, and it would also “secure a common food-supply base in the Ukraine for some time to come.” ((Letter from Hitler to Mussolini dated July 21, 1941. Sontag 1948, 349-353.)) Mussolini provided 62,000 troops for the invasion. ((Robert Kirchubel, Operation Barbarossa, 1941 (1): Army Group South (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2003), 26.))

On June 22, Hitler gave his proclamation to the German people concerning the invasion. He listed a host of reasons for attacking Russia. Ultimately, he fell back on his anti-Jewish and anti-Bolshevik views that he listed in Mein Kampf. He concluded that “the hour has come in which it has become necessary to oppose this conspiracy of the Jewish-Anglo-Saxon warmongers and likewise the Jewish ruling powers in the Bolshevik control station at Moscow.” ((The speech was given in Berlin on June 22, 1941. Max Domarus, The Complete Hitler: A Digital Desktop Reference to His Speeches and Proclamations, 1932-1945 (Wauconda: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 2007), 2451.)) He went on to say that the mission of the eastern front was “no longer protection of individual countries, but the securing of Europe and, hence, salvation of all.” ((Domarus 2007, 2451.))

The result was a four-year struggle that generated death tolls never seen in war. Outside of the confines of battle deaths and civilians caught in the cross-fire, Nazi Germany inflicted the following deaths.

- 6,500,000 people died through imposed famine and resulting diseases.

- 3,000,000 POWs were killed.

- 1,224,000 people were killed through executions, massacres, or bombing of civilian populations.

- 876,000 Jews were targeted and killed.

- 650,000 people died through forced labor.

Hitler’s Justification

To grasp how so many people could be killed in such horrendous ways, one must remember that Hitler viewed the people of Russia as an “inferior race” ruled by Jews who were bent on world domination. By 1941, Hitler no longer saw them as humans, but as “beasts.” ((In an appeal on September 12, 1941 for funds to fuel the Eastern campaign, Hitler said that the German soldier is fighting “against an enemy who is not human, but consists of beasts.” Domarus 2007, 2478.)) After the war, one general told of an order Hitler gave to his commanders.

Before the attack on Russia, the Fuhrer summoned all commanders in chief and all persons connected to the high command to a conference on the pending attack on Russia. In this conference, he said that weapons different from those used against the west were to be employed against the Russians. He said that the war between Russia and Germany was a war between races. He said that the Russians were not a party to the Geneva Convention and hence Russian prisoners of war need not be treated in accordance with the stipulations of the Geneva Convention. ((Testimony given by General Franz Halder during Nuremberg Trials. Domarus 2007, 3133.))

This rationalization gave Hitler his justification to bomb civilians, kill POWs, impose famine, and force labor on the people of Russia.

A captured Soviet soldier being searched by German soldiers early in the conflict. ((John Erickson and Ljubica Erickson, Hitler Versus Stalin: The Second World War on the Eastern Front in Photographs (London: SevenOaks, 2007), 26.))

Sieges, Starvation, and Bombing of Civilian Populations

Hitler’s armies surrounded cities, starved them, and bombed them. One such besieged city was Leningrad. Here was a city that Hitler believed must “disappear utterly from the earth’s surface.” ((Statement made by Hitler on August 6, 1942 at a dinner with his generals. H. R. Trevor-Roper, ed., Hitler’s Table Talk, 1941-1944: His Private Conversations (New York: Enigma Books, 2008), 466.)) After the first few months of the siege, Hitler professed to have a policy of encircling and starving the city instead of moving in troops so as not to “sacrifice one more [German] than is absolutely necessary.” ((The speech was given in Berlin on November 8, 1941. Domarus 2007, 2507.)) As the war raged on, so did the death toll. Leningrad was sieged from 1941 through 1944. From starvation alone, an estimated 641,803 civilians died in the city. ((Official Soviet government statistic. Rummel 1992, 130.)) At the height of the bombing, an estimated 4,000 civilians were dying a day. ((John Keegan, The Second World War (New York: Viking, 1990), 198.))

Citizens of Leningrad killed from German bombing in October, 1941. ((Erickson 2007, 49.))

Forced Labor

Captured prisoners of war as well as civilians in the east were often used by Nazi Germany to perform labor. When a railway was needed in 1941, Hitler ordered that it should be built “by the ruthless employment of Russian prisoners of war.” ((Hitler’s War Directive No. 36 issued on September 22, 1941. H. R. Trevor-Roper, ed., Hitler’s War Directives, 1939-1945 (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2004), 157.)) Later that year when the Russian winter set in, Hitler began making defensive plans. Instead of putting German laborers through the harsh conditions, he ordered that “Young workers classified as essential will be released from their employment on a large scale and will be replaced by prisoners and Russian civilian workers, employed in groups.” ((Hitler’s War Directive No. 39 issued on December 8, 1941. Trevor-Roper 2004, 170.)) German workers were replaced by those of the “inferior race” or the “beasts.”

Throughout the war, forced labor would be employed. The laborers endured rough weather, lack of food, and dehydration. People were literally worked to death.

Exterminations, Massacres, and Jews

Traveling behind the German army’s advance were the Einsatzgruppen, ((German for “Special Operation Units”.)) mobile units tasked with eliminating various groups such as communists, political leaders, and Jews. These men carried out executions themselves, but also helped the German army in executions. Germany adopted a policy of killing 50-100 hostages for every German soldier killed. ((Erickson 2007, 64.))

One such act of vengeance occurred after the German headquarters in Soviet Kiev was bombed. A notice was put out that all Jews were to be relocated from the city. Nearly 34,000 Jews showed up. They were taken outside the city, stripped naked, and shot. The official report from the Einsatzgruppen said they killed 33,771 Jews over a two-day period in September, 1941. ((Operation Situation Report No. 101 published on October 2, 1941 reported on the massacres of September 29 and 30. Martin Gilbert, The Second World War: A Complete History, Revised Ed. (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1991), 239.)) Before the end of the year, these men would officially report killing half a million people. ((Ian Kershaw, Hitler 1936-1945: Nemesis (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001), 468.))

After 1941, the Einsatzgruppen were replaced with concentration camps designed for mass extermination on a cheaper scale.

German soldiers performing executions. ((Erickson 2007, 67.))

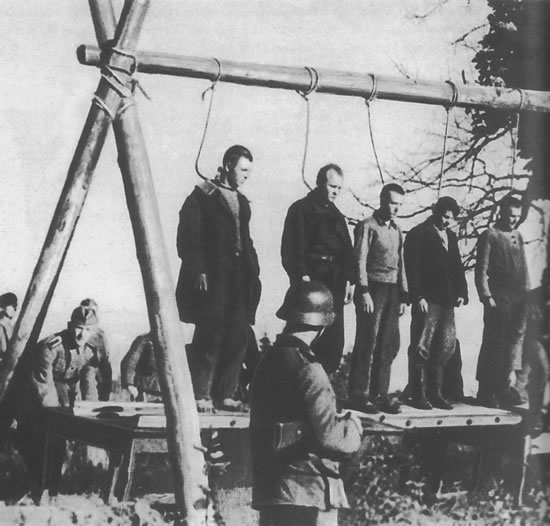

Hanging of Soviets in the Moscow region. ((Erickson 2007, 64.))

The people of the Soviet Union by far suffered in greater numbers than any other population that was attacked by Nazi Germany. In less than four years, 12,500,000 civilians died at the hands of Germany. This does not include the estimated 7,500,000 to 13,600,000 civilians and troops that were killed by Germans in combat. ((Michael Clodfelter, Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures, 1618-1991, vol. 2 (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 1992), 955-956.))

References

Clodfelter, Michael. Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures, 1618-1991, vol. 2. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 1992.

“Country Comparison: Population.” Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook. (22 June 2009).

Domarus, Max. The Complete Hitler: A Digital Desktop Reference to His Speeches and Proclamations, 1932-1945. Wauconda: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 2007.

Erickson, John and Ljubica Erickson. Hitler Versus Stalin: The Second World War on the Eastern Front in Photographs. London: SevenOaks, 2007.

Gilbert, Martin. The Second World War: A Complete History, Revised Ed. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1991.

Grenkevich, Leonid D. and Josef Washington Hall. The Soviet partisan movement 1941-1945: A Critical Historiographical Analysis. Portland: Frank Class, 1999.

Keegan, John. The Second World War. New York: Viking, 1990.

Kershaw, Ian. Hitler 1936-1945: Nemesis. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001.

Kirchubel, Robert. Operation Barbarossa, 1941 (1): Army Group South. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2003.

Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. trans. Ralph Menheim. Boston: Mariner Books, 1999.

Rummel, R. J. Democide: Nazi Genocide and Mass Murder. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1992.

Sontag, Raymond James, ed. and James Stuart Beddie, ed. Nazi-Soviet Relations, 1939-1941: Documents from the Archives of the German Foreign Office. Washington D.C.: Department of State, 1948.

Trevor-Roper, H. R., ed. Hitler’s Table Talk, 1941-1944: His Private Conversations. New York: Enigma Books, 2008.

——, ed. Hitler’s War Directives, 1939-1945. Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2004.