In doing some research on the Battle of Marathon, I was reading the late A. R. Burn’s Persia and the Greeks (1962). He gets into the nitty-gritty of topography, religion, logistics, strategy, and tactics. Over the course of 13 pages describing the lead up to the battle and its aftermath, Burn evoked numerous battles from other periods of history. These were always seemingly to help the reader have a frame of reference for a point he was making. For example, he explained the importance of establishing a beachhead was made obvious at Suvla and Anzio.

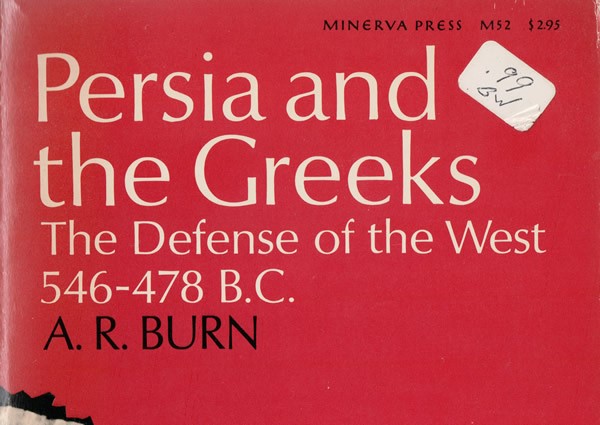

But the list of battles he evoked are numerous over the 13 pages, which was more than 1 per every 2 pages. ((A. R. Burn, Persia and the Greeks: The Defense of the West 546-478 B.C. (Minerva, 1968), 243-256.))

- Bannockburn (1314), twice!

- Morgarten (1315)

- Spanish Armada (1588)

- Ticonderoga (1777)

- Suvla (1915)

- Anzio (1944)

So in discussing an ancient Greek battle, Burn felt the need to evoke everything from the Scottish Wars of Independence to the world wars. But why? Did I really need someone to mention amphibious landings from the world wars to help me understand that beachheads are important?

Has this practice died out?

I don’t have any empirical data, but I get the impression that I see this more often in older works. For example, Tom Holland’s account of Marathon makes no mention of other wars or battles; it just covers Marathon.

In the late Alfred H. Burne’s The Crécy War (1955), he evoked the battles of Badon (516), Waterloo (1815), and Hastings (1066) twice. ((Alfred H. Burne, The Crécy War (Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1955), 169-186.)) Some may be quick to point out that this was his inherent military probability theory at work, which used 20th-century logic to solve medieval mysteries in warfare. However, Burne evoked Hastings just to make the point that it was difficult to count the size of the French army at Crécy just as it probably was at Hastings. ((Alfred H. Burne, The Crécy War, 176.)) What value does that add?

Conversely, Kelly DeVries’s Infantry Warfare (1996) dedicates an entire chapter to Crécy that only mentions battles that also involved Edward III. He does mention Courtrai (1302) too, but only to point out that some medieval chroniclers compared it to Crécy. ((Kelly DeVries, Infantry Warfare in the Early Fourteenth Century (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 1996), 155-175.))

Still, historians such as Victor Davis Hanson keep the tradition alive. In describing the Battle of Delium (424 BC), he evokes Napoleon and Wellington at Waterloo, Patton in World War II, Shiloh, Gettysburg, Somme, and Verdun to name a few in a mere 3 pages. ((Victor Davis Hanson, A War Like No Other: How the Athenians and Spartans Fought the Peloponnesian War (New York: Random House, 2005), 142-144.))

Don’t get me wrong. Comparing battles from history can add value. In a survey work such as Keegan’s A History of Warfare or Hart’s Strategy, it makes sense. These historians were trying to trace the evolution of trends and themes in warfare throughout history.

But when a historian writes a work about a specific period, what is the need to evoke battles from every other period? And what is the need to do it continuously?