A crusader in remarkably accurate 13th-century armor and his cherished Chinese sword have been set in stone for nearly 800 years and on display in New York City for the last century.

So it’s no wonder the medieval limestone effigy that once covered the tomb of Jean d’Alluye now dons the cover of the newly released Remembering the Crusades and Crusading (2017). It is a fitting image for the book’s theme, as editor Megan Cassidy-Welch tells us

So it’s no wonder the medieval limestone effigy that once covered the tomb of Jean d’Alluye now dons the cover of the newly released Remembering the Crusades and Crusading (2017). It is a fitting image for the book’s theme, as editor Megan Cassidy-Welch tells us

As a material object, [the effigy] was intended to bring to mind the dead crusader himself and create a lasting remembrance of him. But it was also intended to stimulate the individual viewer to remember God, a profound and self-conscious remembering that brought together subjective and social practices of memoria. ((Megan Cassidy-Welch, ed., Remembering the Crusades and Crusading (New York: Routledge, 2017), 4.))

Little is known about the life of Jean d’Alluye. After a 3-year trek to the Holy Land (1241-1244), he returned to his abbey in France, dying 4 years later (1248). His effigy portrays an armed, yet passive and pious crusader that stands upon a lion, conveying strength.

Anyone visiting The Cloisters museum can get face-to-face with this crusader. Even more impressive is how it survived this long and ended up in New York.

Jean d’Alluye’s Journey to New York City

The effigy originally covered the tomb of Jean d’Alluye in the Cistercian abbey of La Clarté-Dieu in Northern France. The abbey was destroyed shortly after the French Revolution (1789-1799), but the effigy survived and reportedly served as a footbridge, facedown across a stream for decades. It was discovered and kept for safekeeping in a nearby castle (Château d’Hodebert), at least by 1855 per surviving records. Eventually, a Parisian art dealer acquired it in 1905-1906. George Grey Barnard purchased it in 1910 along with many other medieval objects he was collecting at the time. He made it part of his ambitious Cloisters Museum in New York City, opened in 1914. Finally, John D. Rockefeller Jr. bought the museum and donated it to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1925. ((Peter Barnet and Nancy Wu, The Cloisters: Medieval Art and Architecture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 9-11, 87, figure 51; Megan Cassidy-Welch, ed., Remembering the Crusades and Crusading (New York: Routledge, 2017), 9; James J. Rorimer, Medieval Monuments at the Cloisters as They Were and as They Are, rev. ed. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1972), 60-62.))

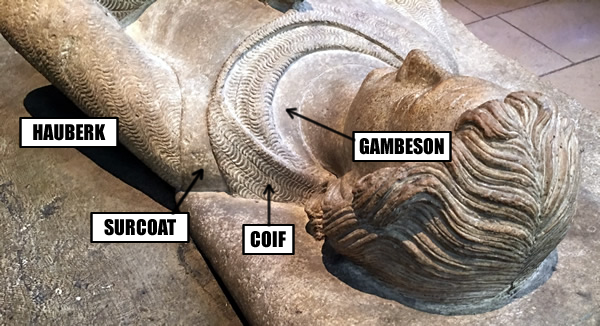

A 2014 restoration has left the effigy much brighter in the images on this page than on the cover of Remembering the Crusades and Crusading, providing us with an even clearer picture of the effigy’s armor.

Jean d’Alluye 13th-century Crusader Armor

Given what we know of crusader armor, the effigy lacks any clear anachronisms. The triangular shield matches those popular among European infantry at the time. While the kite shield had been around for several centuries, by the mid-13th-century, they sported flattened tops and were much smaller, possibly due to the prevalence of leg armor, which d’Alluye is wearing. The shield’s design became known as the “heater” shield, due to its shape matching that of an iron. ((Kelly DeVries and Robert Douglas Smith, Medieval Military Technology, 2nd. ed. (Ontario: University of Toronto Press, 2012), 70.))

The chain mail shirt, or hauberk, matches the period, as it is able to cover him from shoulder to thigh. ((Kelly DeVries and Robert Douglas Smith, Medieval Military Technology, 2nd. ed. (Ontario: University of Toronto Press, 2012), 72)) Around his neck is a coif, an extension of the chain mail that can cover his head and neck. In addition, he sports a cloth surcoat over the chain mail, which would have been sleeveless at the time. Finally, under the chain mail is a gambeson, a leather or cloth layer to protect his skin from the chain mail. ((Janetta Rebold Benton, Materials, Methods, and Masterpiece of Medieval Art (Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2009), 263-264.)) This is a seemingly small detail in the effigy, but you can see it right under his neck.

Another aspect of Jean d’Alluye’s equipment is the dangling chain mail mittens, or “mufflers” as they have been called. This 1248 depiction fits perfectly with what we know of the evolution of European chain mail, as the 12th-century saw the lengthening of the sleeves until they completely covered the back of the hands by the 13th-century. The mittens would have left palms exposed. ((Kelly DeVries and Robert Douglas Smith, Medieval Military Technology, 2nd. ed. (Ontario: University of Toronto Press, 2012), 68.))

Possibly the most remarkable aspect of this 1248 depiction of a crusader from France is it matches almost everything in a c. 1250 depiction of another crusader from the Westminster Psalter in England. In this separate image (below), we can see the armored legs, houberk from shoulder to thigh, chain mail mittens, the surcoat, the gambeson barely visible under his right thigh, and the coif covering his head and neck. ((David Nicolle, Arms & Armour of the Crusading Era, 1050-1350: Western Europe and the Crusader States (London: Greenhill Books, 1999), 75-76, figure 190, 394.)) All that is missing is heater shield.

That of course leaves us with d’Alluy’s curious sword, which does not match the Westminster Psalter sword whatsoever.

A Chinese sword?

Much of the historical commentary on Jean d’Alluye’s effigy up until 1991 covered its survival and journey. That year, museum curator Helmut Nickel aggressively questioned the origin of d’Alluye’s sword, which was unlike any other sword from the period or regions, both European and Middle Eastern.

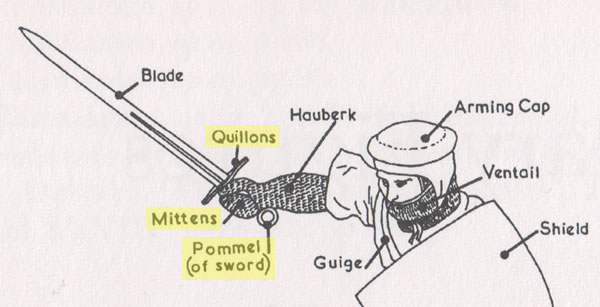

With the sword sheathed, we can only see the pommel, grip, and quillons (or cross-guard), but this was enough for Nickel to perform his analysis.

The pommels of 13th-century European swords were either circular or a pointed oval and Islamic swords were small buttons or acorn shapes, whereas d’Alluye’s sword has a flower-like appearance. This is the same style of pommel that rose to prominence in 12th-century China, represented today by surviving art.

More importantly, there are no examples of European or Islamic quillons curved in this fashion from the 13th-century or earlier, which instead tended to be straight bars (see Westminster Psalter image above). The style of d’Alluye’s quillons matched those found in China as far back as the Bronze Age. ((Helmut Nickel, “A Crusader’s Sword: Concerning the Effigy of Jean d’Alluye,” Metropolitan Museum Journal 26 (1991): 123-128.))

Nickel theorized the sword could have been “traded peacefully along the Silk Road, or was carried by a raider in the conquering hordes of the Mongols,” which then could have found its way to d’Alluye via “the bazaar of some Levantine port” or as “booty on a Syrian battlefield.” ((Helmut Nickel, “A Crusader’s Sword: Concerning the Effigy of Jean d’Alluye,” Metropolitan Museum Journal 26 (1991): 128.))

Megan Cassidy-Welch believes it “was probably purchased in Syria,” but she too is convinced of its Chinese origin. More importantly, she sees it as d’Alluye’s “own souvenir of a military adventure and a reminder of the great cultural and spatial distances he traveled.” ((Megan Cassidy-Welch, ed., Remembering the Crusades and Crusading (New York: Routledge, 2017), 9.))

Without any records, there is some conjecture and thus, not all historians are prepared to declare this a Chinese sword. David Nicole, prior to Nickel’s research, described it as a “somewhat fanciful sword” that “may reflect Crusading aristocracy of France.” ((David Nicolle, Arms & Armour of the Crusading Era, 1050-1350: Western Europe and the Crusader States (London: Greenhill Books, 1999), 33, 372, figure 39.)) Later, he described it simply as a “relatively light sword” and a “fine Spanish sword.” ((David Nicolle, French Medieval Armies 1000-1300 (London: Osprey, 1991), 33, 45-46.)) This is curious as there is no sword matching this style from 13th-century Spain among the thousands of European and Islamic images in Nicolle’s multi-volume Arms & Armour of the Crusading Era.

Unfortunately, in Janetta Rebold Benton’s Materials, Methods, and Masterpiece of Medieval Art (2009), she talks in detail about the historical accuracy of every piece on the effigy including the scabbard holding sword, but never mentions the sword. ((Janetta Rebold Benton, Materials, Methods, and Masterpiece of Medieval Art (Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2009), 262-264.))

With historians such as Megan Cassidy-Welch accepting Nickel’s analysis, the case against the sword’s Chinese origins has become weak. Nickel’s analysis is convincing and it is clear a crusader returning from the Holy Land brought back a Chinese souvenir that impressed him, as well as the local community that carved it along with his image in limestone nearly 800 years ago.