Sun Tzu tells us that if we put our troops “in the most desperate straits, they will have no fear,” and having “nowhere else to turn, they will stand firm” (9.37). Some interpretations indicate this means putting one’s back to a river, an unorthodox and typically disastrous move for armies throughout history. However, for the Red Stick Indians in March 1814, it had been a successful tactic, especially against American troops and their Creek Indian allies. ((The Battle of Holy Ground (December 23, 1813) saw a similar disposition. Ove Jensen, “Horseshoe Bend: A Living Memorial,” in Tohopeka: Rethinking the Creek War and the War of 1812, ed., Kathryn E. Holland Braund (Pebble Hill, 2012), 147.))

This is crucial in understanding why, on March 27, 1814, the Red Stick Indians had established a formidable position on a peninsula behind a thick barricade that even the opposing commander, Colonel Andrew Jackson, admired. However, their tactic of fighting surrounded with a river to their backs would meet disaster in what became known as the Battle of Horseshoe Bend during the Creek War (1813-1814) in present-day Alabama.

Here is what you can expect if you visited the Horseshoe Bend battlefield today.

Horseshoe Bend requires both walking on foot and viewing a map to appreciate it fully. The Tallapoosa River wraps around, creating a horseshoe shape, which is a natural defense.

The Red Stick Indians surely had this in mind when consolidating their 1,000 warriors here. Toward the southern part of the peninsula, they established a village where roughly 350 women and children took shelter. The warriors focused on building and occupying a barricade of trees at the neck of the peninsula, which connected to the river on both sides, represented in white below.

Jackson was impressed with the defensive position of the Red Sticks.

This bend, which resembles in its curvature that of a horse-shoe includes I conjecture, eighty or a hundred acres. The river immediately around it, is deep, and somewhat upwards of 100 yards wide. As a situation for defense it was selected with judgment, and improved with great industry and art. ((Andrew Jackson to Governor Willie Blount, April 5, 1814. Quoted in Jensen, “Horseshoe Bend: A Living Memorial,” 148-149.))

Based on American accounts, we know that on March 27 Jackson began marching toward Horseshoe Bend at 6:30 AM, arriving at 10:00 AM. Jackson’s plan was to bring 2,000 troops and artillery down the peninsula while surrounding the river with another 1,300 men, nearly half of which were Cherokee and other Indian allies. Jackson placed his artillery on a hill indicated by the blue marker below.

The main obstacle for Jackson was of course the barricade and unfortunately, there is not a contemporary detailed description of it. On the battlefield today, there are only white posts that mark where the barricade stood.

Here is the same view Jackson would have had of the barricade, facing to the south.

At around 10:30 AM, Jackson’s artillery bombarded the barricade for two hours with little effect. His artillery was small with only a 6-pounder and a 3-pounder. Today, there is a replica with a monument on what is now known as “Gun Hill.”

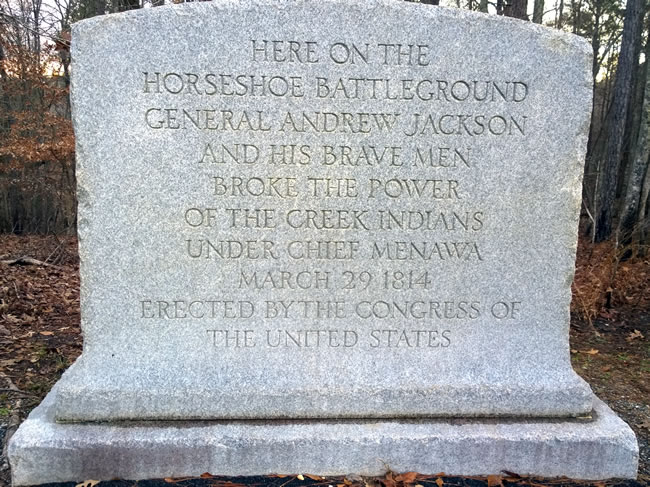

Erected in 1918, the monument has a typo, as the date of the battle if off by two days.

Facing south from the hill, you can see the white posts in the distance just above the left wheel. This was the view of Jackson’s artillery, as they bombarded the barricade.

At 12:30 PM, the battle changed dramatically, when Cherokees from the south, crossed the river and attacked the village. This is a view of the river, facing south from the peninsula.

This is a view from the southern tip of the peninsula facing north. There is where the Red Stick village stood.

When the village was endangered, the 1,000 warriors at the barricade faltered and some moved south to protect it. As the ranks thinned at the barricade, Jackson sent in his 2,000 infantry from the north, assaulting the barricade. Jackson’s forces took the barricade and continued push south.

Here is another view of the village location from the north, facing south. This would have been the same view as Jackson’s men who captured the barricade and continued south.

The results for the Red Stick warriors were devastating. There were 557 dead on the peninsula with another 250 to 300 shot along the Tallapoosa River. The final tally was 807 to 857 Red Stick warriors killed out of 1,000, plus 350 women and children captured. Jackson’s forces suffered 49 killed and 154 wounded. ((Jensen, “Horseshoe Bend: A Living Memorial,” 153.))

Aside from the battlefield, the museum is small, but well worth perusing. Along with telling the story of the battle and the Creek War, it has some original artifacts, such as these projectiles found on the battlefield.

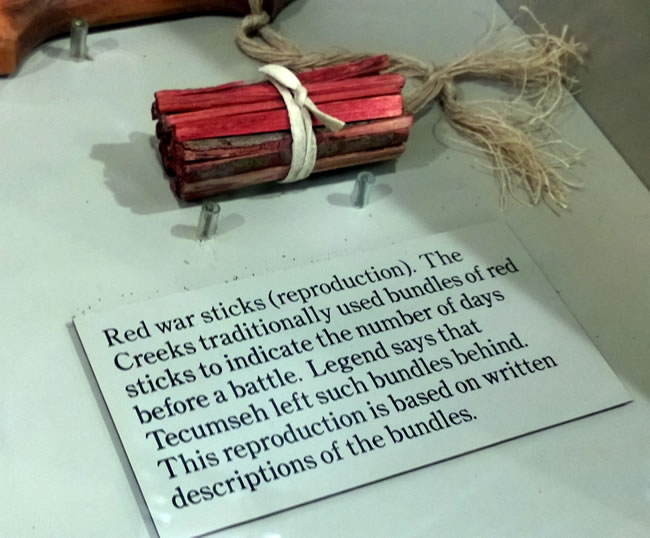

There are also some great recreations, such as these Red War Sticks, which apparently Indians used to countdown to battle.

Horseshoe Bend was the climax of the Creek War, which ultimately led to a large territory grab by the US of what was predominately present-day Alabama. It remains a lesser known battle in America’s history, but if visitors take the time to explore the battlefield, there is a rich story to gleam from the experience.

Further Reading

The best book I have come across that cover Horseshoe Bend is Tohopeka: Rethinking the Creek War and the War of 1812 (2012), which contains a series of essays from scholars and park rangers.

For a work that focuses on the battlefield itself, see The Ghosts of Horseshoe Bend (2014).