With the sesquicentennial of the American Civil War quickly approaching, it is appropriate to examine how past civilizations commemorated the 150-year anniversaries of their major conflicts. One such group was the Greeks who commemorated the sesquicentennial of Xerxes’ invasion (480 BC) to the exact year (330 BC) by sanctioning Alexander the Great (r. 336-323) to invade the Persian Empire. Alexander invaded, conquered, and burned the Persian capital, Persepolis, after thoroughly looting it. The following article describes how the event came about.

Xerxes

Many westerners will be familiar with Persian King Xerxes (r. 486-465 BC) from the 300 film (2007). Although outrageously exaggerated in many ways, the movie captured the spirit of how Herodotus, Plutarch, and others wrote about the Battle of Thermopylae and the last stand of Leonidas and his Spartans. Toward the end, the movie quickly transitions from the death of the Spartan king to a year later at the Battle of Plataea (479 BC), as the Greeks charge screaming toward the faceless Persian lines. Then the credits roll.

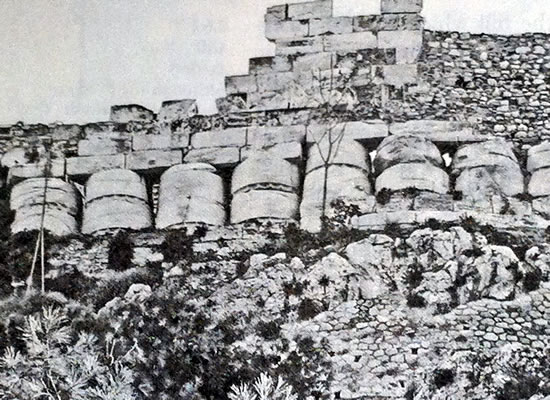

With all the excitement, it is important to remember that the Persians won the Battle of Thermopylae, creating a path for the invaders to march further into Greece. After the battle, Xerxes decapitated Leonidas and impaled his head on a stake. ((Herodotus, The Histories, 7.238.1. This translation comes from the Robert B. Strassler translation (New York: Anchor Books, 2007).)) As the Persians continued their march, numerous cities gave in to Xerxes’ demand for “earth and water,” a sign of submission to the Persian king. ((Xerxes demanded earth and water from all Greeks except for Athens and Sparta. Unlike the movie that depicts Leonidas tossing Persian ambassadors into a pit, the event occurred 10 years prior when Xerxes’ father, Darius I, invaded Greece (490 BC). Both Athens and Greece killed the ambassadors in similar fashion. Herodotus 7.32.)) As he continued his march, Xerxes burned the cities that refused. Herodotus recorded the destruction of 15 cities including a near-vacant Athens. ((Herodotus 8.32.2-8.33-34, 8.50.2, 8.53.2, 8.56.)) The latter still plagued the Greeks 150 years later. Although they defeated Xerxes and cleared Greece of the Persian army, many of the Greeks, especially the Athenians, never forgot about the destruction of the Acropolis of Athens and its sacred temples within. Today, there are still remnants of an unfinished temple that the Persians burned during Xerxes’ invasion.

The following column drums were intended for a new temple in Athens on the Acropolis before Xerxes damaged them with fire. The Athenians did not reuse them and instead kept them on display in the city. ((Photo from Robert B. Strassler, The Landmark Herodotus: The Histories (New York: Anchor Books, 2007), 622.))

A War of Revenge

Another figure with a long memory was Isocrates (436-338 BC), who wrote several works and gave numerous speeches in an attempt to unite the loose bodies of city-states into a power that could then invade the Persian Empire. When Philip II of Macedon (r. 359-336 BC), Alexander’s father, came to power and spent several decades establishing a hegemony over Greece, Isocrates saw his chance and began writing directly to the Macedonian king, calling on him to attack Persia (Worthington 2008, 169). It is not clear whether he had any influence on Philip, but the Macedonians began making strides toward invasion.

Once Philip established his hegemony over most of Greece, he formed an alliance with the heads of the city-states. ((The Peloponnese including the Spartans remained outside of Philip’s hegemony. He was content to leave them isolated. Paul Cartledge, The Spartans: The World of the Warrior-Heroes of Ancient Greece, from Utopia to Crisis and Collapse (New York: Vintage Books, 2003), 232.)) The alliance had two purposes. First, the members swore to protect each other, Philip, and his heirs. ((The text on a surviving stele from Athens records part of the oath taken by the members of the alliance, the Corinthian League. The members swore by Zeus and other gods to do no harm to the other members, as well as “make war upon” those who do. More importantly, they swore allegiance to the “kingdom of Philip and his descendants” (e.g., Alexander). Phillip Harding, ed. and trans., From the End of the Peloponnesian War to the Battle of Ipsus. Translated Documents of Greece & Rome 2. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 98-99.)) Second, they planned “to make war on the Persians in the Greeks’ behalf and to punish them for the profanation of the temples.” ((Diodorus, Historical Library, 16.89.2. This translation comes from the C. Bradford Welles translation (Cambridge: Harvard University, 1963).)) The alliance sanctioned an invasion of Persia and provided troops and supplies for the effort. ((Diodorus 16.89.3.))

Although there is no indication of Philip’s long-term goals, Greek historian Ian Worthington theorizes that they could have been a combination of money, resources, personal glory, and securing Philip’s position in Greece. ((Ian Worthington, Philip II of Macedon (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 167-169.)) Worthington also believes that Philip’s aims were limited, probably never going further than Asia Minor, modern-day Turkey. ((Worthington 2008, 169.)) Still, Philip planned to invade Persia. Whether his ultimate goal was total conquest, it is impossible to know, because the night before the invasion, he was assassinated (336 BC). ((Diodorus 16.94.3.))

The Rise of Alexander

Alexander became the new king of Macedonia at age 20. He sat with the same alliance of Greeks that his father formed. They reaffirmed the mandate to extract vengeance on Persia and Alexander accepted. ((Diodorus 17.4.9.)) Regardless of Alexander’s or his father’s ultimate goals, vengeance was still the battle cry, Alexander sought “satisfaction for the offences which the Persians had committed against Greece.” ((Diodorus 17.4.9.)) He only had six years before the arrival of the sesquicentennial of Xerxes’ invasion and there was much work ahead of him.

After Alexander spent a few years solidify his dominance over his Greek hegemony, he invaded Asia Minor, the western-border of the Persian Empire (334 BC). In just four years, Alexander had secured modern-day Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, Egypt, Iraq, and the western-half of Iran. In between one of his numerous battles and sieges, Alexander wrote to Persian King Darius III (r. 336-330 BC) explaining why he had invaded Persia: “Your ancestors came to Macedonia and the rest of Greece and did us great harm, though you had suffered no harm before them. I, having been made leader of the Greeks and wishing to take revenge on the Persians, made the crossing into Asia…” ((Arrian, The Campaigns of Alexander, 2.14.5. This translation comes from the Pamela Mensch translation (New York: Anchor Books, 2010).))

The Sesquicentennial

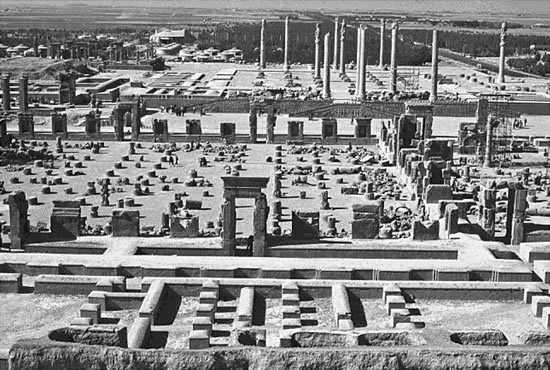

On January 31, 330 BC, Alexander arrived at Persepolis, the Persian capital. ((Date of arrival in Peter Green, Alexander of Macedon, 356-323 B.C.: A Historical Biography (Berkeley: University of California, 1991), 314.)) The city itself was older than Xerxes’ rule, as inscriptions on ruins in the city reveal that Xerxes’ father, Darius I (r. 522-486 BC), constructed and dedicated the city. ((Amélie Kurt, The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period (London: Routledge, 2010), 488-489.)) Before Alexander and his army arrived, he told his troops that it was “the most hateful of the cities of Asia” and he allowed them to plunder uncontrollably. ((Diodorus 17.20.1.)) There was plenty of loot, because they managed to arrive before the Persians could clear out the royal treasury or any other riches. The descriptions of the sack are typical from the ancient world. Alexander’s troops looted for more than a day and even fought with each over the booty. ((Diodorus 17.20.4-5.)) They killed the males and enslaved the women. One ancient historian poetically observed, “As Persepolis had exceeded all other cities in prosperity, so in the same measure it now exceeded all others in misery.” ((Diodorus 17.20.6.))

As his men plundered, Alexander walked through the city and passed a toppled statue of Xerxes. He stopped and stared at for a moment. Plutarch theorized that Alexander considered setting it upright, but eventually continued walking. ((Plutarch, Alexander, 37.5. This translation comes from the Robert Waterfield translation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).)) He moved onto the royal palaces and secured the loot within to fund further his conquests. ((Diodorus 17.21.2.)) After the dust settled, Alexander and his men wintered in the city for about four months.

In May, Alexander decided to complete the mandate his father originally secured. He ordered the city burned. One of his men reasoned “it was ignoble to destroy what was now his own property.” He worried that the people of Persia would see him as merely a conqueror and not one who truly wanted to govern. ((Arrian 3.18.11.)) Alexander would not listen. His intention was revenge. He restated the grievances from 150 years prior once more, about how the Persians invaded Greece and burned Athens and its temples. ((Arrian 3.18.12.)) The city burned.

The following is an aerial view of Persepolis. ((Photo from James Romm, ed., The Landmark Arrian: The Campaigns of Alexander (New York: Anchor Books, 2010), 130.))

Some of the ancient historians believe that Alexander burned the city while heavily intoxicated after the suggestion of an Athenian woman who was one of his general’s mistresses. ((Plutarch, Alexander, 38.1-6; Diodorus 17.22.2-3; Quintus Curtius Rufus, The History of Alexander 5.7.3-5. This translation comes from the John Yardley translation (London: Penguin, 2004).)) However, most modern-day historians dismiss this as legend. ((Green 1991, 319-320; N. G. L. Hammond, Alexander the Great: King, Commander and Statesman, 3rd ed. (London: Bristol Classical Press 2001), 170.)) These types of stories exist to explain why Alexander, a 25-year-old conqueror, could be so reckless at times. Archeological evidence indicates that the act was not spontaneous. Excavations of the city reveal that all the rooms were clear of any contents before the fire started. ((Hammond 2001, 17.)) If Alexander suddenly set the city aflame, there would be remnants of burnt items. Instead, only stone remains. Excavations could not find a single gold or copper piece. In addition, all statues and art were defaced in some form or fashion. Cracks in the stones indicate that the stones were heated and then intentionally splashed with water in order to cause such cracking. ((Eugene N. Borza, “Alexander at Persepolis,” in The Landmark Alexander, ed. James Romm, 367-370 (New York: Anchor Books 2010), 368.))

Alexander would conquer the remnants of the Persian Empire and establish his own on top of it. Did the Greeks feel avenged? We do not know for sure, but the remnants of Xerxes’ destruction are still visible in Athens. Did the Persians regret the actions of Xerxes? Again, we do not know. One ancient historian believed that Alexander “was not acting sensibly,” because there could not “be any punishment for Persians of a bygone era.” ((Arrian 3.18.12.)) Regardless, invasion, conquest, and destruction are how the Greeks commemorated the sesquicentennial of Xerxes’ invasion of Greece.

Bibliography

Arrian. The Campaigns of Alexander. In The Landmark Arrian: The Campaigns of Alexander, translated by Pamela Mensch and edited by James Romm, 1-315. New York: Anchor Books, 2010.

Borza, Eugene N. “Alexander at Persepolis.” In The Landmark Arrian: The Campaigns of Alexander, edited by James Romm, 367-370. New York: Anchor Books, 2010.

Cartledge, Paul. The Spartans: The World of the Warrior-Heroes of Ancient Greece, from Utopia to Crisis and Collapse. New York: Vintage Books, 2003.

Diodorus. Historical Library XVI. 66-95 and XVII. Diodorus of Sicily in Twelve Volumes 8. Translated by C. Bradford Welles. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1963.

Hammond, N. G. L. Alexander the Great: King, Commander and Statesman. 3rd ed. London: Bristol Classical Press, 2001.

Harding, Phillip, ed. and trans. From the End of the Peloponnesian War to the Battle of Ipsus. Translated Documents of Greece & Rome 2. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Herodotus. The Histories. In The Landmark Herodotus, edited by Robert B. Strassler and translated by Andrea L. Purvis, 1-722. New York: Anchor Books, 2007.

Kurt, Amélie. The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period. London: Routledge, 2010.

Plutarch. Greek Lives: A Selection of Nine Greek Lives. Translated by Robin Waterfield. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Rufus, Quintus Curtius. The History of Alexander. Translated by John Yardley. London: Penguin Books, 2004.

Worthington, Ian. Philip II of Macedonia. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

With the sesquicentennial of the American Civil War quickly approaching, it is appropriate to examine how past civilizations commemorated the 150-year anniversaries of their major conflicts. One such group was the Greeks who commemorated the sesquicentennial of Xerxes’ invasion (480 BC) to the exact year (330 BC) by sanctioning Alexander the Great (r. 336-323) to invade the Persian Empire. Alexander invaded, conquered, and burned the Persian capital, Persepolis, after thoroughly looting it. The following article describes how the event came about.

Many westerners will be familiar with Persian King Xerxes (r. 486-465 BC) from the 300 film (2007). Although outrageously exaggerated in many ways, the movie captured the spirit of how Herodotus, Plutarch, and others wrote about the Battle of Thermopylae and the last stand of Leonidas his Spartans. Toward the end, the movie quickly transitions from the death of the Spartan king to a year later at the Battle of Plataea (479 BC), as the Greeks charge screaming toward the faceless Persian lines. Then the credits roll.

With all the excitement, it is important to remember that the Persians won the Battle of Thermopylae, creating a path for the invaders to march further into Greece. After the battle, Xerxes decapitated Leonidas and impaled his head on a stake (Herodotus 7.238.1). As the Persians continued their march, numerous cities gave in to Xerxes’ demand for “earth and water,” a sign of submission to the Persian king. As he continued his march, Xerxes burned the cities that refused. Herodotus records the destruction of 15 cities including a near-vacant Athens (Herodotus 8.32.2-8.33-34, 8.50.2, 8.53.2, 8.56). The latter still plagued the Greeks 150 years later. Although they eventually defeated Xerxes and cleared Greece of the Persian army, many of the Greeks, especially the Athenians, never forgot about the destruction of the Acropolis of Athens and its sacred temples within. Today, there are still remnants of an unfinished temple that the Persians burned during Xerxes’ invasion.

A War of Revenge

Another figure with a long memory was Isocrates (436-338 BC), who wrote several works in an attempt to unite the loose bodies of city-states into a power that could then invade the Persian Empire. When Philip II of Macedon (r. 359-336 BC), Alexander’s father, came to power and spent several decades establishing a hegemony over Greece, Isocrates saw his chance and began writing directly to the Macedonian king, calling on him to invade Persia (Worthington 2008, 169). It is not clear whether he had any influence on Philip, but the Macedonians began making strides toward invasion.

Once Philip established his hegemony over most of Greece, he formed an alliance with the heads of the city-states. The alliance had two purposes. First, the members swore to protect each other, Philip, and his heirs. Second, they planned “to make war on the Persians in the Greeks’ behalf and to punish them for the profanation of the temples” (Diodorus 16.89.2). The alliance sanctioned an invasion of Persia and provided troops and supplies for the effort (Diodorus 16.89.3).

Although there is no indication of Philip’s long-term goals, Greek historian Ian Worthington theorizes that they could have been a combination of money, resources, personal glory, and securing Philip’s position in Greece (Worthington 2008, 167-169). Worthington also believes that Philip’s aims were limited, probably never going further than Asia Minor, modern-day Turkey (Worthington 2008, 169). Still, Philip planned to invade Persia. Whether his ultimate goal was total conquest, it is impossible to know, because the night before the invasion, he was assassinated (336 BC) (Diodorus 16.94.3).

Enter Alexander

Alexander became the new king of Macedonia at age 20. He sat with the same alliance of Greeks that his father formed. They reaffirmed the mandate to extract vengeance on Persia and Alexander accepted (Diodorus 17.4.9). Regardless of Alexander’s or his father’s ultimate goals, vengeance was still the battle cry, Alexander sought “satisfaction for the offences which the Persians had committed against Greece” (Diodorus 17.4.9). He only had six years before the arrival of the sesquicentennial of Xerxes’ invasion and there was much work ahead of him.

After Alexander spent a few years solidify his dominance over his Greek hegemony, Alexander invaded Asia Minor, the western-border of the Persian Empire (334 BC). In just four years, Alexander had secured modern-day Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, Egypt, Iraq, and the western-half of Iran. In between one of his numerous battles and sieges, Alexander wrote to Persian King Darius III (r. 336-330 BC) explaining why he had invaded Persia: “Your ancestors came to Macedonia and the rest of Greece and did us great harm, though you had suffered no harm before them. I, having been made leader of the Greeks and wishing to take revenge on the Persians, made the crossing into Asia…” (Arrian 2.14.5).

The Sesquicentennial

On January 31, 330 BC, Alexander arrived at Persepolis, the Persian capital (Green 1991, 314). The city itself was older than Xerxes’ rule, as inscriptions on the ruins of the city reveal that Xerxes’ father, Darius I (r. 522-486 BC), constructed and dedicated the city (Kurt 2010, 488-489). As Alexander and his army approached the city, he told his troops that it was “the most hateful of the cities of Asia” and he allowed them to plunder the city (Diodorus 17.20.1). The descriptions of the sack are typical from the ancient world. Alexander’s troops looted for more than a day and even fought with each over the booty (Diodorus 17.20.4-5). They killed the males and enslaved the women. One ancient historian poetically observed, “As Persepolis had exceeded all other cities in prosperity, so in the same measure it now exceeded all others in misery” (Diodorus 17.20.6).

As his men plundered, Alexander walked through the city and passed a toppled statue of Xerxes. He stopped and stared at for a moment. Plutarch theorized that he considered setting it upright, but eventually continued walking (Plutarch, Alexander, 37.5). Alexander moved onto the royal palaces and secured the loot within to fund further his conquests (Diodorus 17.21.2). After the dust settled, Alexander and his men wintered in the city. He eventually went out on a raiding party in April, returning in May.

Alexander then decided to complete the mandate his father originally secured. He ordered the city burned. One of his men reasoned “it was ignoble to destroy what was now his own property.” He worried that the people of Persia would see him as merely a conqueror and not one who truly wanted to govern (Arrian 3.18.11). Alexander would not listen. His intention was revenge. He restated the grievances from 150 years prior once more, about how the Persians invaded Greece and burned Athens and its temples (Arrian 3.18.12). The city burned.

Some of the ancient historians believe that Alexander burned the city while intoxicated after the suggestion of an Athenian woman (Plutarch, Alexander, 38.1-6; Quintus 5.7.3-5; Diodorus 17.22.2-3). However, most modern-day historians dismiss this as legend (Green 1991, 319-320; Hammond 2001, 170). Archeological evidence indicates that the act was not spontaneous. Excavations of the city reveal that all the rooms were clear of any contents before the fire started (Hammond 2001, 17). If Alexander suddenly set the city aflame, there would be remnants of burnt items. Instead, only stone remains. Excavations could not find a single gold or copper piece. In addition, all statues and art were defaced in some form or fashion. Cracks in the stones indicate that the stones were heated and then splashed with water (Borza 2010, 368).

That is how the Greeks commemorated the sesquicentennial of Xerxes’ invasion of Greece. Alexander would eventually clean up the remnants of the Persian Empire and establish his own on top of it. Did the Greeks feel avenged? We do not know for sure, but the remnants of their temples remained visible in Athens. Did the Persian regret the actions of Xerxes? One ancient historian believed that Alexander “was not acting sensibly,” because there could not “be any punishment for Persians of a bygone era” (Arrian 3.18.12).Bibliography

Arrian. The Campaigns of Alexander. In The Landmark Arrian: The Campaigns of Alexander

Borza, Eugene N. “Alexander at Persepolis.” In The Landmark Arrian, edited by James Romm, 367-370. New York: Anchor Books, 2010.

Cartledge, Paul. The Spartans: The World of the Warrior-Heroes of Ancient Greece, from Utopia to Crisis and Collapse. New York: Vintage Books, 2003.

Herodotus. The Histories. In The Landmark Herodotus, edited by Robert B. Strassler and translated by Andrea L. Purvis, 1-722. New York: Anchor Books, 2007.

Kurt, Amélie. The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period. London: Routledge, 2010.

Rufus, Quintus Curtius. The History of Alexander. Translated by John Yardley. London: Penguin Books, 2004.

Worthington, Ian. Philip II of Macedonia. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.