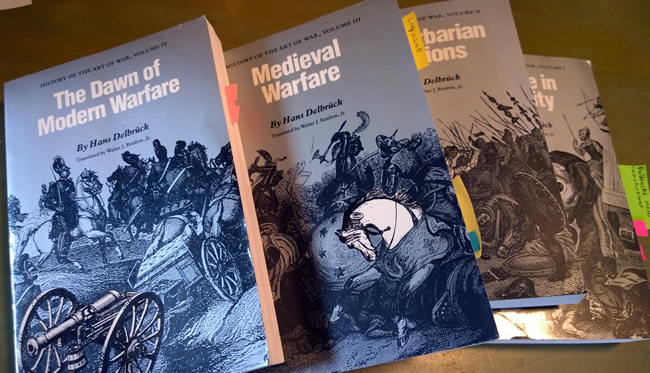

In a previous article, I covered how military historians have stumbled over themselves to heap praise upon Hans Delbrück. Now I will demonstrate why that praise is warranted. In a future article, I will demonstrate why it is not.

The overarching question for these articles is why military historians should care about Hans Delbrück. Quite simply, Delbrück has left us with timeless principles that are still prevalent 85 years after his death.

Here are two tangible examples.

Troop Estimates

The most commonly invoked principle by historians was Delbrück’s critical eye toward troop estimates from ancient and medieval accounts. It is easy to find a classicist that believes “Delbrück first enshrined the vital concept that military historians must assess ancient figures concerning size, casualties, and expenditures with scientific, geographical, and demographic parameters.” ((Victor Davis Hanson, “The Modern Historiography of Ancient Warfare,” in The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Warfare, vol. 1, eds., Philip Sabin, Hans Van Wees, and Michael Whitby (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 8.)) Likewise, even the most critical of medievalists will agree that because of Delbrück, medieval “scholars have come to reject as basically unreliable the figures found in narrative sources and even to regard with great suspicion the numbers found in a great variety of documentary sources.” ((Bernard S. Bachrach, “Early Military Demography: So Observations on the Methods of Hans Delbrück,” in The Circle of War in the Middle Ages, eds. Donald J. Kagay and L. J. Andrew Villalon (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 1999), 3.))

Any historiographical analysis of Delbrück will mention how he debunked Herodotus’s estimates of 4,200,000 Persians invading Greece under Xerxes. ((Hans Delbrück, History of the Art of War, 4 vols., trans. Walter J. Renfroe, Jr. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990), 1:35.)) Others may go further to include how he debunked the Herodotus’s estimates of Mardonius’s 300,000 troops and 110,000 Greeks at Plateau, or Caesar’s estimate of 368,000 Helvetians. ((Ibid., 1:35-36, 37, 470.)) His methods for challenging the estimates included calculating lengths of columns, tallying necessary draft animals for supplies, and comparing the numbers with recent battles and campaigns to test the reasonability of the recorded estimates and speed of armies.

All of this played into Delbrück’s overarching belief that “a military-historical study does best to start with the army strengths.” More dramatically, “without a definite concept of the size of the armies, therefore, a critical treatment of the historical accounts, as of the events themselves, is impossible.” ((Ibid., 1:33.))

Topography

Another lasting principle in the field of military history came from Delbrück’s focus on topography, deconstructing terrain to interpret events on battlefields. He believed “if we are familiar with the armament and the combat methods of the opposing armies, then the terrain is such an important and eloquent witness to the nature of a battle that we may risk reconstructing the course of the battle in its general outline, since, after all, there is no doubt as to the outcome.” ((Ibid., 2:77.))

When one reads his chapter on the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest (9 AD), one is predominately reading a topographical study. Delbrück evaluated all possible locations, available archeological evidence, and existing theories about how the battle transpired on these grounds. ((Ibid., 2:69-96.)) Delbrück believed it was important to determine the location of the battle and then become intimately familiar with that location.

Adaptors of Delbrück’s Principles

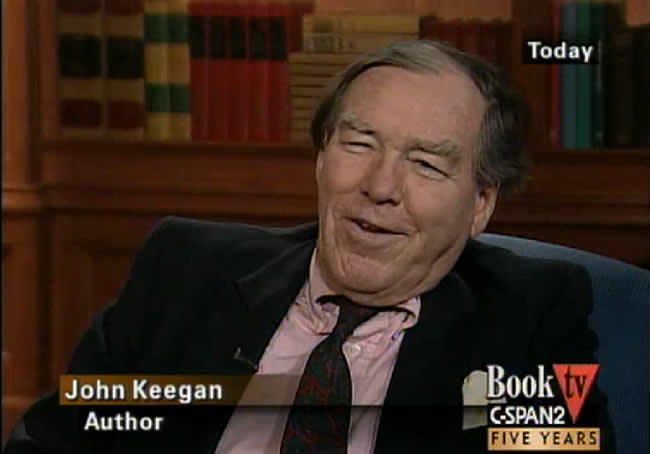

With the heavy emphasis on topography, the influence becomes more apparent as John Keegan placed Delbrück squarely in the middle of his historiographical treatment of military history in his seminal work, The Face of Battle (1978). Keegan emphasized that every historian “ought also to get away from papers and walk about his subject wherever he can find traces of it on the ground.” He credited Delbrück with demonstrating “that it was possible to prove many traditional accounts of military operations pure nonsense by mere intelligent inspection of the terrain.” ((John Keegan, The Face of Battle (New York: Penguin, 1978), 32.))

Interpreting battlefields has become a staple in military history, as military historians continuously emphasize its importance. For example, Michael Rayner, a founder of the UK-based “The Battlefields Trust,” believes that “many would hesitate if not always refrain from writing about a battle without visiting its site,” because “the battlefield is a historical source demanding attention, interpretation like any written or other account. To understand a battle, one has to understand the battlefield.” ((Michael Rayner, ed., Battlefields: Exploring the Arenas of War, 1805-1945 (London: Struik, 2006), 8.))

Philip Preston puts it more succinctly, “Just as military commanders consider the selection of a battle ground of primary importance, so military historians who follow place equal importance on these choices in their interpretation and analysis of warfare.” ((Philip Preston, “The Traditional Battlefield of Crécy,” in The Battle of Crécy, 1346, eds., Andrew Ayton and Philip Preston (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2005), 111.))

Similarly, when describing how to do military history, Stephen Morillo believes “Nothing beats walking around a battlefield, castle, or fortification for getting an idea of the parameters of physical reality in warfare.” ((Stephen Morillo and Michael F. Pavkovic, What is Military History?, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Polity, 2013), 113.))

Then there are the unpublished comments. Among prolific authors, bloggers, and licensed battlefield guides at places such as Gettysburg and Antietam, I have heard how they really feel about prominent historians who supposedly rarely trek the fields where Americans fought and died. There is clear disdain and dismissiveness for any historian who does all the necessary archival research, but spends little time on the battlefield. Walking that ground has become the fieldwork of the military historian. Doing it earns you respect. Neglecting it regulates you to spectator status.

Yet in judging the lasting influence of Delbrück’s principles, the most tangible example comes from a 2003 interview of John Keegan on C-SPAN.

Here, Keegan is not writing, but speaking off the cuff, answering a slew of questions from the host and random callers. When asked by one such caller to describe his methodology in writing military history, Keegan first addressed topography, “I analyze the events in terms of, always, quite material factors. One of these is geography, the location, what the terrain was like, how the terrain would have influenced the [sic] on each side.” Keegan then moved onto troop estimates.

Another is, which I think is absolutely fundamental and I spend a great deal of time with, is what is called the order of battle. And that’s to say making an exact list of who was involved…I always say that unless you’ve got an exact order of battle and you know, for example, how many at Waterloo, how many French units there were and how many British and allied units there were on each side, and know exactly their strength and position and who commanded them, that you can’t do the account of the battle. Literally, the account in both senses—you can do the story of the battle and you can’t do the bill correctly.

He believed “it’s only after I’ve done those things that I begin to think of the more imaginative, less material aspects.” ((John Keegan, interview by Brian Lamb, In Depth, C-SPAN2, November 2, 2003.))

Keegan’s unscripted answer is roughly the same that any military historian would give today when asked how to write about a battle or campaign, and we have Delbrück to thank for that.

In the next article, we will examine some of Delbrück’s outmoded principles and his critics.

Even More Principles

Delbrück’s lasting influence is by no means limited to these two topics. Other historians have emphasized how he brought the concept of wars of annihilation and attrition to the forefront of military thought, further solidified the connection of war and politics in the Clausewitzian vein, fought the German military over the civilian right to criticize strategy, and produced the first scientific analysis of war throughout the ages. However, my goal here was to provide two tangible examples of Delbrück’s influence that any military historian—young or old—was most likely to have encountered, as well as evidence of their prevalence not already considered.