A friend shared this with me, because I am a historian or something.

In history, there is what happened and then there is how cultures interpreted what happened. The former tends to be straightforward, but the latter is murky.

In terms of our interpretation, we struggle with the availability of information and popular belief. Again, the former is easy to grasp, but the latter is difficult.

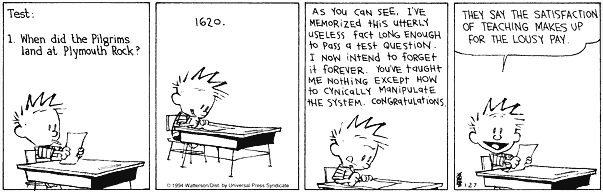

However, history should be much more than just memorizing dates. Knowing what happened and when is one thing, but examining how people have remembered that history takes us fascinating new heights.

For example, if we examine the War of 1812, we can determine the United States aggressively started the war, poorly executed it, and was lucky to exit it. However, the people of America were more prone to believe that they somehow “won” the war via a victory at New Orleans after the war was over. The implications of this collectively accepted lie led to many trends in the country including the aggressive pursuit of Manifest Destiny and the election of a president based on populism.

In another example, the Egyptian Sultan Saladin (r. 1174-1193) successfully set back crusaders in the Middle East, yet he remained a relatively obscure figure among Muslims until the German Kaiser visited the region in 1898. While there, he made a pilgrimage to Saladin’s tomb to pay homage to the medieval sultan. By doing so, the Kaiser brought Saladin to the forefront of Islamic memory (See Jonathan Riley-Smith’s The Crusades, Christianity, and Islam). Today, I cannot find a Muslim in my office who is not familiar with Saladin.

Again, all of this was possible because of how people remembered history as opposed to what actually happened in history.