The Franklin Institute in Philadelphia has a Genghis Khan exhibit through the rest of 2015. Here is what you can expect.

The exhibit focuses on the rise, dissemination, and fall of the Mongolian empire, paying particular attention to the amalgamation of cultures—Mongolian, Chinese, Japanese, Persian, and European. For example, there is one fourteenth-century sword sporting elements from all of the above.

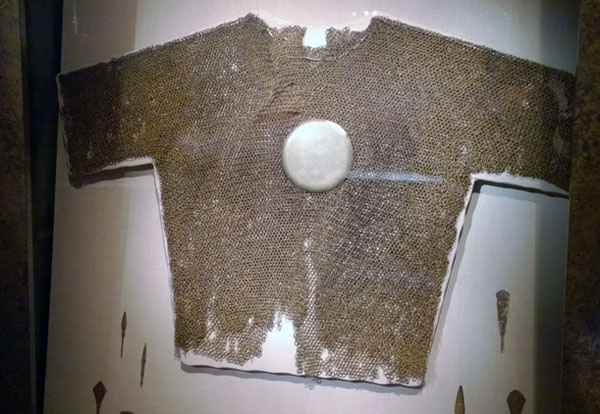

In terms of artifacts, there are far more than I envisioned. The exhibit boasts a restored recurve bow, arrowheads, chainmail, helmets, a chair, and numerous swords. In addition, there are plenty of artifacts related to the regions the Mongolians conquered. These are the best part of the exhibit, as few westerners will find themselves this close to artifacts from the Mongolian Empire.

The most impressive artifact was an imperial passport from an ambassador of Kublai Khan. Being one of two remaining in the world (c. 1240 AD), it states “I am the emissary of the Khan. If you defy me, you die.”

The next most impressive artifact is a Mongolian firearm. The inscription gives us the date of its creation (1328 AD), which translates roughly to “the last year of the reign of Yesün Temür.” The great-grandson of Kublai Khan, Yesün Temür was emperor of the Yuan Dyanasty for five years (1323-1328).

There are also reproductions of some thirteenth-century Mongolian monuments, as well as a triple crossbow and a traction trebuchet, the first I’ve seen in person.

There are also numerous wooden busts of some of Genghis’s descendants including Chagatai Khan and Kaidu. The latter warred with his uncle Kublai, founder of the Yuan Dynasty in China.

The Mongolians are proud of their country’s “hero,” as stated in one of the numerous videos strewn throughout the exhibit. In fact, these videos, though informative, are the most annoying aspect. The first room, which is not big, has three competing televisions talking about Genghis Khan, horse riding, and life on the Steppe. All of them are blaring and distracting to the point you can hear all three of them audibly regardless of where you stand.

The hero- and philosopher-status of Genghis is emphasized throughout the exhibit with little mention of the millions dead and enslaved. Women simply become “wives” instead of raped captives, the more accurate term. Genghis incorporates (not enslaves) Chinese siege engineers into this army, his meritocracy that the exhibit emphasizes squashed age-old squabbles.

Regions are simply conquered with no mention of the razing of cities, mass enslavement, or massacres. For example, Muslim chronicles tell us how in 1221, the Mongols razed the city of Merv, killing around 700,000 occupants. That same year, they captured Gurganj, enslaving 100,000 women, children, and artisans while killing the remaining occupants. To destroy Gurganj, the Mongols destroyed a nearby dam, flooding the city and ensuring the Oxus River flowed into the Caspian Sea for the next 300 years. ((See J. J. Saunders, The History of the Mongol Conquests (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1971), 59-60.))

There are many more stories like this, but the exhibit never goes into this kind of gruesome detail.

Some artifacts lack context. On several occasions, I found myself pondering questions like who used this thousand-year-old comb.

These criticisms aside, the exhibit is worth viewing if you have any interest whatsoever in Genghis Khan or the Mongolians. We caught the night-showing for $20/ticket, which is a fair price for what we saw.