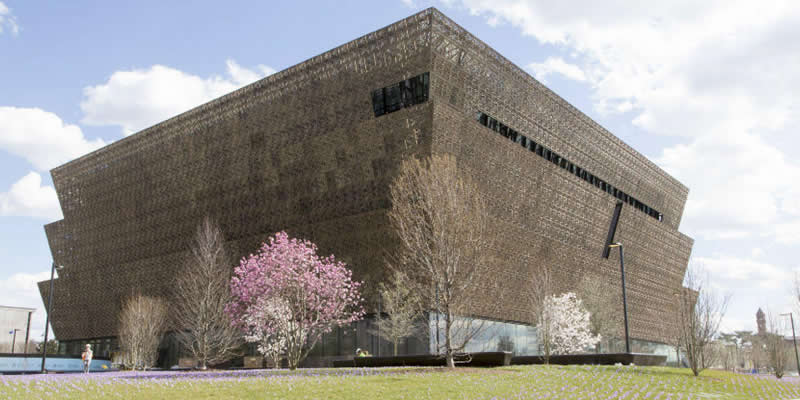

My wife and I were fortunate to get a last-minute invite to the National Museum of African American History & Culture in Washington D.C. I say fortunate, because you can’t even get tickets right now due to the high demand. Their website literally instructs you to try back in April for advanced tickets. I say this not to brag, but to rejoice that history is in such high demand and explain why I took off a Thursday from work to trek down to D.C. for this experience.

The museum is massive, often overwhelming. Coupled with the throngs of visitors and the hundreds of years of gruesome history, it is an exhausting experience. We went through all 6 floors over about 6 hours and we skimmed some sections. This is the type of place that folks will need to visit several times over the course of a lifetime to fully appreciate.

As for the structure of the museum, it is nothing short of brilliant. Starting at 1400 AD, visitors move through 3 floors of 6 centuries of history in America. There are stories, maps, statistics, and artifacts—visitors walk through a room with the ambiance of a lower deck as they view remnants of slave ships. It is dark, dank, and crowded. Once you push through the crowd, you realize you are viewing an excavated beam from a ship that crashed in 18th-century, losing its precious cargo of some 200 Africans.

The museum has taken pains to tackle the conflicting history of America head-on. White American fought for freedom from British while the British offered freedom to blacks who remained loyal. The Confederacy sought to defend and expand slavery while the Union initially fought to preserve the Union. Lincoln is no crusading saint and the museum emphasizes that he did not want to end slavery, only prevent its expansion back in 1861.

Among the artifacts from the Civil War was a diary of a soldier from the 54th Massachusetts. As I was looking closely at it, trying to decipher the handwriting, a black man in a wheelchair read the nearby panel and turned to a black teenager, “Have you seen that movie? Glory?” The kid shook his head. “We are going to watch that movie tomorrow!” I smiled because my parents made me watch it when I was kid too.

The most disturbing parts of the museum included photographs of lynchings. What struck me was not the hanging lifeless bodies, but the white males posing in the pictures, even smiling. One of my friends exclaimed, “My god, they look like they’re taking a selfie!” The museum has marked some of these images with a thick red outline to warn parents.

There were several displays about the Ku Klux Klan, including photographs, videos, and even hoods. A group of black teenagers appeared to read every panel, one saying how it gave him the chills.

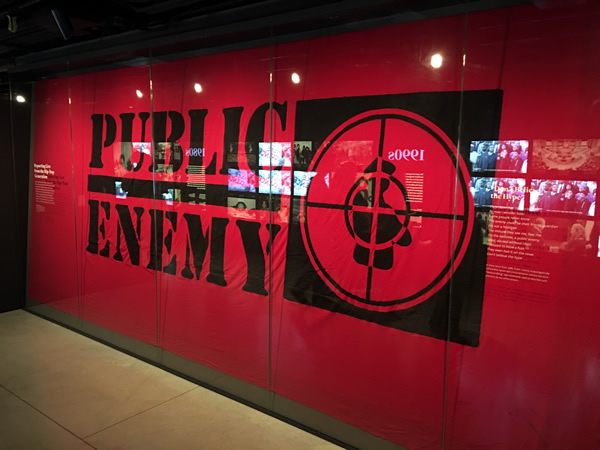

Before we entered the museum, I made an inappropriate joke that it was the 21st anniversary of the murder of Biggie Smalls and how apropo that we were visiting the museum. Initially, the conclusion of the group was that any references to him, Tupac, or other rappers would be inappropriate to the theme. Yet, when we got to the end of the chronological history of the museum, there was a massive Public Enemy display, one of my favorite raps groups. As we watched a short video with montages from the 1990s, I smiled at one of my friends when images of Biggie flashed while a Tupac song played in the background. As the montage continued, a young teenage girl reacted to an image of OJ Simpson’s Bronco racing down the highway, “Oh, why would they show that!” My friend quipped, “Because that’s part of the history.”

As for me, I couldn’t think of a better inclusion for the history section of the museum. Before I opened a history book, I learned about the Atlantic slave trade from Public Enemy’s incredible track “Can’t Truss It” (1991).

I heard several times while at the museum, from my own party and others, how recent some of these events happened, especially from the Civil Rights Era. My friend lamented how their parents likely saw some of the reporting for the lynchings, shaking his head, “That’s not that long ago!” And that was probably one of the more impactful aspects of the museum, especially with its breakdown of Jim Crow laws by state. Even Arizona had laws as late as the 1970s discrediting marriages between certain races. The message people got was, “A lot of this wasn’t even a lifetime ago.”

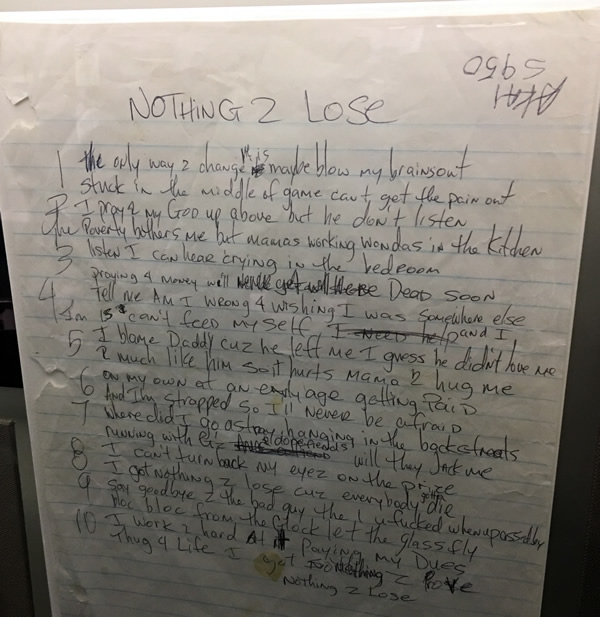

Lest I leave you with the impression that the museum focuses on only the darker aspects, the upper parts of the museum celebrate black culture and entertainment. From TV to film to music to literature, one panel described black culture as America’s greatest export. That’s hard to argue with when you’re looking at artifacts worn by Michael Jackson, Ray Charles, and Prince. They even had a handwritten poem by Tupac on display alongside Slick Rick’s eyepatch.

Looking back on my photos and notes, I realize that I wrote about the historical-related stuff, but photographed the arts. While going through the 6 centuries of black history in America, it felt awkward and even inappropriate to yank out a phone for most of the displays. There are images that many of us have seen countless times.

Think about the infamous 1863 photo of Gordon (NSFL) after a whipping in Louisiana. The image is horrifying and I have seen it at just about every Civil War museum. However, the African American Museum gave that image context with a copy of the photo carried by Civil War soldiers. Gordon’s image and pain went on to remind (inform?) Union soldiers of the horrors of slavery. That sort of context is lacking when quickly flashed in countless documentaries.

I hope that is what others can get out of this museum—context. Context for black American history–from the gruesome stuff to the art that we all enjoy.