The deathbed image of English King Edward I (r. 1272-1307) refusing to show mercy to William Wallace is a modern one, but also completely false.

Edward had Wallace executed nearly 2 years before he himself died. The king was far from his deathbed at that point. Thanks, Braveheart.

Remarkably, this is not the most fantastical depiction of Edward on his deathbed and the medieval world left us with 2 amazing versions.

Edward wanted his bones sent to war against the Scots

The first depiction and more apropos to the theme in Braveheart was Edward instructed his knights to carry his bones with them to war against the Scots. As French Chronicler Jean Froissart (c. 1337-1405) describes it

When [Edward] perceived he could not recover, he called to him his eldest son, who was afterward king, and made him swear, in presence of all his barons, by the Saints, that as soon as he should be dead, he would have his body boiled in a large cauldron until the flesh should be separated from the bones; that he would have the flesh buried and the bones preserved; that every time the Scots should rebel against him, he would summon his people, and carry with him the bones of his father. ((This translation comes from Sir John Froissart’s Chronicles of England, France and the Adjoining Countries, trans. Thomas Johnes, vol. 1 (Hafod Press, 1803), 50. However, I did replace the long s (ʃ) characters with s characters, for sanity’s sake.))

Yes, Wallace was captured and executed, but Robert the Bruce continued the struggle for Scottish independence. Froissart tells us that Edward “believed most firmly, that, as long as his bones should be carried against the Scots, they would never be victorious.” ((Froissart, Chronicles, 50.)) This fits in with the notion as to why Wallace was victorious at Stirling Bridge, but not at Falkirk where Edward was present and victorious.

Pope Boniface VIII’s bull against dismembering bodies notwithstanding, what better way to demonstrate Edward’s determination to subdue the Scots? The makers of Braveheart could have included this tale in addition to the one they portrayed in the film.

The story does have its problems though. Jean Froissart wrote it nearly 200 years after Edward’s death. Although Froissart is explicit in his desire to write true history, his focus was on contemporary events during the Hundred Years War, not England’s wars with Scotland. In addition, there is zero contemporary evidence that records such a story. Historian Michael Prestwich theorizes “it reflects Edward’s later reputation, rather than recording a genuine deathbed scene.” ((Michael Prestwich, Edward I (New Haven: Yale University Press), 557.))

Edward wanted his heart carried on crusade

The second but no less fanciful story of Edward on his deathbed has him requesting that 140 knights take his heart on crusade to the Holy Land. The evidence is flimsy at best, coming from an old poem that quotes Edward saying

I bequeath my heart rightly

that it be written at my devise

over the sea that it be sent

with fourscore knights all of repute

in war that are wary and wise

against the heathen for to fight

to win the cross which lies low

myself I would [go] if I could. ((Peter Cross, Thomas Wright’s Political Songs of England: From the Reign of John to that of Edward II (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 247.))

The Old English poem itself was a translation from a French poem dating back to the same year as Edward’s death (1307). ((Walter W. Skeat, “’Elegy on the Death of King Edward I,’ The Modern Language Review 7, no. 2 (1912): 149.)) This puts the origin of the story very close to the event and there is at least one modern historian who seemingly evokes the story as fact. ((“Edward I (d.1307), himself a former crusader, ordered that his heart should be carried to the Holy Land by 140 knights.” Agostino Paravincini Bagliani, “The Corpse in the Middle Ages: The Problem of the Division of the Body,” in The Medieval World, eds. Peter Linehan and Janet L. Nelson, (New York: Routledge, 2001), 329.))

At age 29, Edward became a crusader who spent a lot money and energy, but accomplished little. Over the course of 4 years, his crusade took him through France, North Africa, Cyprus, Sicily, and finally Acre. There, he conducted a few raids and several failed sieges. Toward the end, he survived an assassination attempt, a story that preceded him upon his return. ((A good overview in Prestwich, Edward I, 66-85.)) Thus, the crusade did more to further Edward’s reputation than it did toward the Christian cause in the Holy Land.

Still, there is no contemporary evidence supporting the poem that claims Edward wanted his heart taken to war. ((Elizabeth A. R. Brown, “Death and the Human Body in the Later Middle Ages: The Legislation of Boniface VIII on the Division of the Corpse,” Viator 12 (1981): 230n33; Prestwich, Edward I, 557.)) The tale is similar to that of Robert the Bruce and his heart, of which there is substantial evidence.

So what did Edward want on his deathbed?

In reality, Edward likely asked his nobles to look after his son, Edward II. ((English translation of the episode in The Brut or the Chronicles of England, vol. 1, ed. Friedrich W. D. Brie (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., 1906), 203-204.)) At age 23, the latter was a decade younger than when his father received the crown. In addition, Edward I had experience fighting in a civil war and a crusade before he came to rule.

This is the story that comes from The Brut, a chronicle composed in Anglo-Norman after 1272 and extended to cover history through 1333. After its English translation in 1400, it was further amended to include history through 1419.

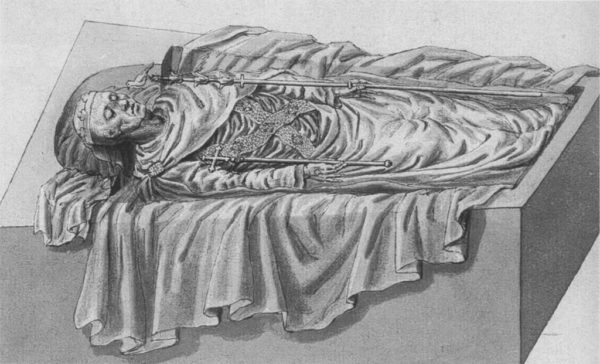

While not nearly as exciting, this story does match with the fact that Edward’s entire body was never boiled or dismembered, and instead interred at Westminster Abbey. There, it remained undisturbed until 1774 when the dean and a group of history enthusiasts opened the tomb and examined the body. It was remarkably complete. ((Prestwich, Edward I, 566-577.))

The poet and artist William Blake even made a sketch.

The stories of Edward wanting his heart and bones appear to have been simply medieval lore. The story of Edward relishing the death of Wallace while on his own deathbed is pure Hollywood.