Frank Miller’s first issue of Xerxes: The Fall of the House of Darius and the Rise of Alexander finally hit shelves this week and here is the historical hottake (see review of Xerxes #2).

We’ve been hearing about Frank Miller’s follow-up to his 300 miniseries for years. When 300: Rise of an Empire finally hit theaters in 2014, I gave up (lost interest?) in ever seeing the comic books that supposedly inspired the film. Yet, there has always been trickles of information, as we learned the series was still in the works, saw teaser art, learned it would be a prequel, then it would be titled Xerxes, and finally it would be titled Xerxes: The Fall of the House of Darius and the Rise of Alexander.

As many have pointed out, the Xerxes of 300 and Alexander’s capture of the Persian capital are 150 years apart in history. Miller knows this, so I was eager to see how he tied it all together in a 5-issue miniseries.

Ironically, the first issue does not give us Xerxes or Alexander. We barely get Darius. Instead, we get the beginning of the Ionian revolts and an interpretation of the Battle of Marathon (490 BC).

There is much more detail in Miller’s version of the battle than what we saw in the visually-stunning, first 10 minutes of 300: Rise of an Empire. For example, we finally see Miltiades, the real commanders of the Greeks at the battle, as opposed to Themistocles who Miller relegates to a mere captain in the ranks.

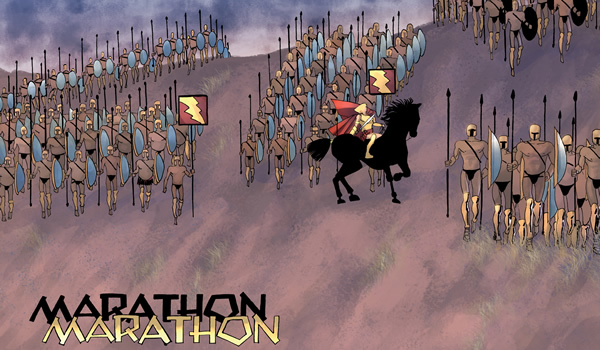

Miller portrays Miltiades as a rich commander, armored with a cape on horseback, which fits with what we know of him—an experienced, aristocratic military leader from a well-to-do family. Miller also portrays him as effeminate with golden curls, lightening earrings, eyeshadow, and pouty lips. One of the Greeks mocks Miltiades as a “fop,” an early modern phrase for what we’d call a “metrosexual”—well-dressed, superb hygiene, and not necessarily homosexual. It’s an odd word choice for a comic book in the ancient world, as it’s a post-medieval term, but certainly out of vogue nowadays.

Miller has Miltiades explain the tactics of the Greeks at Marathon, who proclaims that they must “shatter the rules of the phalanx.” By this, he explains,

Our center line will thin to four men deep. Our outer flanks will funnel the barbarian hordes between them—then snap around, crushing them like a lobster’s claws.

Herodotus was the original source for what we know of the battle and he described a similar deployment and tactics.

Their line of battle was equal in length to that of the Medes; and as a consequence it was weakest in the centre, where it was only a few ranks deep, while on the two wings it had strength in depth (Hdt. 6.111.3).

As for the battle, Herodotus gives us a single albeit graphic paragraph:

The fighting at Marathon lasted a long time. In the centre, where the Persians themselves and the Sacae were stationed, it was the Barbarians who had the better of it, smashing their way through the Athenian lines, and then pursuing those they had defeated inland. On both the flanks, however, it was the Athenians and the Plataeans who emerged triumphant. The two wings, rather than pursue the routed Barbarians, then used their victory to join forces, and fight those who had broken through the centre – with victory going to the Athenians. As the Persians turned tail, the Athenians set off after them, hacking away, until they reached the sea – at which point they called for fire, and began to grab at the ships (6.113).

Miller manages to generate roughly 15 pages’ worth of comic book spreads from this single paragraph. Although it is difficult to envision the pincer movement described by Miltiades in these pages, it is still entertaining schlock on par with the original 300.

The Spartans are mocked thoroughly for not participating in the battle, as the Greeks likely would have done back then. Miller emphasizes the Greeks at Marathon are “just a pack of potters and tailors and blacksmiths and fishermen—fighting to defend our homes.” This is clearly a juxtaposition to Leonidas’s line in 300 emphasizing the profession of his warriors compared to the potters, tailors, and blacksmiths of the rest of the Greeks. Miller neglects to mention that the Greeks at Marathon were still rich enough to buy their own equipment and honed their tactics through pitched battles among each other. Still, this effort to downplay the Spartans while propping up the rest of the Greeks will likely lead into an issue in the series featuring the Peloponnesian War—the civil war between Athens, Sparta, and their allies. Quite simply, Miller can’t effectively portray a civil war featuring the nearly unbeatable Spartans and disposable Greeks from his 300.

Miller uses the playwright Aeschylus as a quirky character who appreciates weaponry from all cultures and fights with staffs and nunchucks. It’s an interesting take, as Aeschylus’s play The Persians provides us with a unique, almost sympathetic perspective on Darius, Xerxes, and the Persians. Miller’s take is odd and entertaining.

One final image worth pointing out from the comic book is the silhouette of Miltiades standing above the Greeks marching into battle, a pose reminiscent of depictions of Alexander the Great.

Miller will likely portray Alexander just as metrosexual, or foppish as he did Miltiades.

The first issue of Xerxes ends with the Greeks gearing up to make their famous post-Marathon march to Athens. Given that this first issue covers ten years’ worth of material, my hunch is that Miller will do another issue featuring Salamis (480 BC) before moving onto the Peloponnesian War and then Alexander’s conquests.