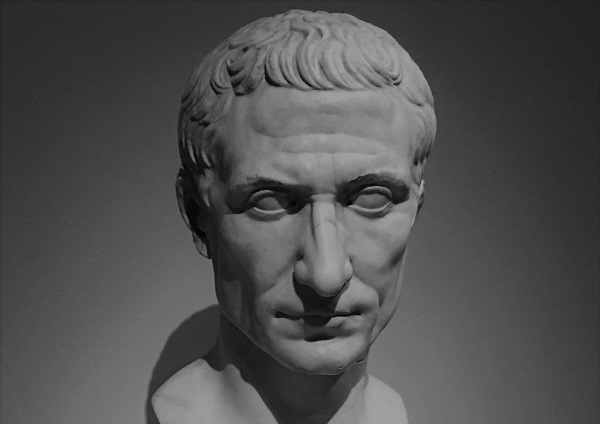

The notion that victors write history finds credence in the Battle of Pharsalus (48 BC). Julius Caesar not only wrote the sole surviving eyewitness account of the battle in his Civil War, but he also provided his own critiques of his defeated opponent, Pompey. Over the past two centuries, historians have followed suit with Caesar’s approach, taking even more liberties to praise the victor while criticizing the defeated.

And how could they not? In his account of Pharsalus, Caesar emphasized his own superior tactics, and the superior morale and courage of his men. More importantly, in a battle where Pompey had more than a 2-to-1 advantage in troop numbers (47,000 over 22,000 according to Caesar), Caesar claimed that he recognized Pompey’s tactics right before the battle started and concocted his own successful countertactics on the spot.

Prior to Pharsalus, Pompey was undefeated even against Caesar. His vanquished foes included a wide range of opponents such as Romans, Gauls, pirates, and gladiators, conquering and securing territory throughout Spain, Sicily, Africa, and the east. For his victories, he celebrated three triumphs, unprecedented at the time for a single general. With superior numbers, it is important to understand how Pompey lost at Pharsalus.

The “Genius” of Caesar

The most simplistic explanation comes from an adoration for Caesar’s mental superiority, as historians have offered plenty of declarative statements on his genius. In his monumental Battle Studies (1870), Ardant du Picq dedicated five pages to quoting Caesar’s account of the battle verbatim, and then he cited “the genius of the chief” as the deciding factor. ((Ardant du Picq, Battle Studies: Ancient and Modern, 8th ed., trans. John N. Greely and Robert C. Cotton (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1921), 70-75.)) The lazy (or rushed!) simply cite Caesar’s “brilliance as a general,” which alone brought victory at the battle. ((Matthew, Bennett ed., The Hutchinson Dictionary of Ancient & Medieval Warfare (Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1998), 52.)) Similarly, Caesar’s “personal military superiority” won the day. ((Michael Grant, The Army of the Caesars (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1974), 27.))

Theodore Ayrault Dodge believed, “From the history of the army of Julius Caesar we have seen that it was the genius of the captain … which won his splendid victories.” ((Theodore Ayrault Dodge, Caesar (Boston: Houghton, 1894), 768.)) Lawrence Keppie vaguely proclaimed that Caesar “had few equals” as a military commander, leaving the reader to assume that Pompey was not one of them. ((Lawrence Keppie, “The Roman Army of the Later Republic,” in Warfare in the Ancient World, ed. John Hackett (New York: Facts On File, 1989), 188.)) David Eggenberger declared Caesar possessed “tactical genius,” which he used to defeat the “once brilliant commander Pompey the Great.” ((David Eggenberger, An Encyclodpedia of Battles: Accounts of Over 1,560 Battles from 1479 B.C. to the Present (New York: Dover, 1985), 331.)) This of course assumes that Pompey somehow lost his brilliance, even after defeating Caesar the month prior at Dyrrhachium.

Even biographers of Pompey can’t hold back. John Leach believed “Pompey’s defeat should be attributed more to Caesar’s tactical genius than his own errors.” ((John Leach, Pompey the Great (London: Croom Helm, 1978), 207.)) In another, Nic Fields believed it was at Pharsalus “that Caesar showed his military genius. It was a genius, in the ultimate analysis, that Pompey lacked.” ((Nic Fields, Pompey (Oxford: Osprey, 2012), 48.))

Although the analyses accompanying these statements vary widely from detailed to nonexistent, each concludes Caesar’s mental superiority that won the battle. Sure, there are some descriptions of the tactics and lines of battle, but Caesar was a mastermind and Pompey was not.

Caesar’s “Genius” and “Superior” Men

Yet, aside from the seemingly throwaway statements above, there is a clear trend to couple Caesar’s genius with the quality of his men. In 1900, Hans Delbrück declared Caesar’s soldiers won “by virtue of their better quality, which the leadership of their commander knew how to utilize in the most brilliant manner.” ((Hans Delbrück, Warfare in Antiquity, trans. Walter J. Renfroe, Jr., History of the Art of War 1 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990), 541.)) In 1924, a Roman history book aimed at schoolchildren tells us that in a difficult situation such as Pharsalus, Caesar “could rely on his men and his own genius to pull him through a pitched battle.” ((E. E. Bryant, A Short History of Rome for Schools (Cambridge, 1924), 224.)) In 1940, F. E. Adcock saw “the rare combination of a general of genius and troops of the very highest skill and aggressiveness.” ((F. E. Adcock, The Roman Art of War Under the Republic (Cambridge: W. Heffer & Sons, 1940), 116.))

More recently, Jonathan P. Roth believed Caesar possessed two advantages at Pharsalus in the form of his men’s experience and “his own military genius.” ((Jonathan P. Roth, Roman Warfare (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 116.)) In her biography of Mark Antony, Eleanor Goltz Huzar credited the victory to “Caesar’s genius and Caesar’s veterans.” ((Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 61.)) Matthew Bunson believed “Caesar’s legions were the finest field army that Rome would ever possess,” which were unbeatable “in the hands of a military genius” such as Caesar. ((Matthew Bunson, Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire, rev. ed. (New York: Facts on File, 2002), 307.))

Finally, in Barry Strauss’s Masters of Command (2012), aptly subtitled “the Genius of Leadership,” his analysis of Pharsalus concludes,

The matchless professionalism of his troops allowed Caesar to take chances, but this was a move of supreme audacity, something that only an exceptional commander would have dared. ((Barry Strauss, Masters of Command: Alexander, Hannibal, Caesar, and the Genius of Leadership (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012), 137-138.))

Time for a Reassessment of Caesar’s Genius

To say that I respect these historians would be an understatement. People like F. E. Adcock, Jonathan P. Roth, and Barry Strauss have produced invaluable works on the study of ancient military history. However, when historians start to sound alike, it typically means it is time to reassess their conclusions, especially when those conclusions are based on the account of one man–the victor.

Future articles will explore the Pharsalus battlefield, Caesar’s account, and other aspects of this battle.