18 February 2026: This bibliography is up to 213 entries and growing. If you have any suggested additions, please do not hesitate to reach out.

As John Aberth pointed out, “There are more books about Arthurian films than perhaps about any other medieval film genre.” This still holds true today and the same goes for articles. This is arguably where the field of cinematic medievalism go its start. While there are some Arthurian aspects mentioned in the larger Medievalism on Screen bibliography, the following entries all focus exclusively on interpretations of Arthurian Legend.

- Introductions and Filmographies

- Pedagogy

- The Holy Grail on Screen

- The Knights of the Round Table (dir. Richard Thorpe, 1953)

- Monty Python and the Holy Grail (dir. Terry Gilliam, 1975)

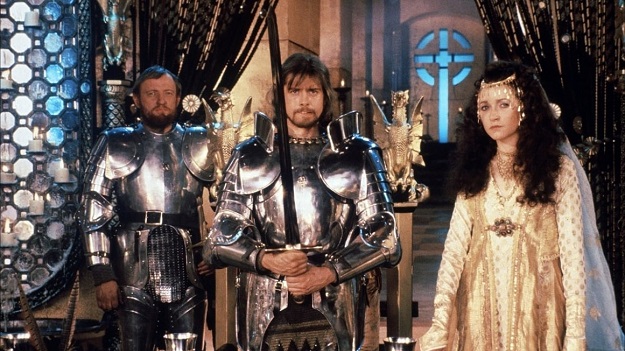

- Excalibur (dir. John Boorman, 1981)

- Parsifal (dir. Hans-Jürgen Syberberg, 1982)

- The Fisher King (dir. Terry Gilliam, 1991)

- King Arthur (dir. Antoine Fuqua, 2004)

- The Green Knight (dir. David Lowery, 2021)

- Looking for Arthur in All the Wrong Places

- Miscellaneous

Introductions and Filmographies

Harty, Kevin J. “Cinema Arthuriana.” In A History of Arthurian Scholarship. Edited by Norris J. Lacy, 252-260. Woodbridge: D. S. Brewer, 2006.

Harty, Kevin J. “Cinema Arthuriana: A Comprehensive Filmography and Bibliography.” In Cinema Arthuriana: Twenty Essays. Revised ed. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 252-301. Jefferson: McFarland, 2002.

This is an alphabetical list of Arthurian films plus alternate titles released between 1904 and 2001. Harty not only provides essential details on each film, but also includes summaries and short commentaries along with references to reviews and discussions on the films. This supersedes the entries below.

Harty, Kevin J. “Cinema Arthuriana: A Filmography.” Quondam et Futurus 7, no. 3 (1987): 5-8.

Kevin J. Harty, “Addenda: Cinema Arthuriana: A Filmography,” Quondam et Futurus 7, no. 4 (1987): 18.

Harty, Kevin J. “Cinema Arthuriana: Translations of the Arthurian Legend to the Screen.” Arthurian Interpretations 2, no. 1 (1987): 95-113.

Harty, Kevin J. “Cinema Arthuriana: A Bibliography of Selected Secondary Materials.” Arthurian Interpretations 3, no. 2 (1989): 119-37.

Harty, Kevin J. “Film Treatments of the Legend of King Arthur.” In King Arthur Through the Ages. Edited by Valerie M. Lagario and Mildred Leake Day, 2:278-290. New York: Garland, 1990.

Harty, Kevin J. “An Alphabetical Filmography.” In Cinema Arthuriana: Essays on Arthurian Film. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 245-247. New York: Garland Publishing, 1991.

Harty, Kevin J. “A Bibliography on Arthurian Film.” In Cinema Arthuriana: Essays on Arthurian Film. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 203-243. New York: Garland Publishing, 1991.

Harty, Kevin J. “Arthurian Film.” The Camelot Project, 1998. Available on the Wayback Machine.

Harty, Kevin J. “A Complete Arthurian Filmography and Selective Bibliography.” In King Arthur on Film: New Essays on Arthurian Cinema. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 233-263. Jefferson: McFarland, 1999.

Harty, Kevin J. “Cinema Arthuriana: An Overview.” In Cinema Arthuriana: Twenty Essays. Revised ed. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 7-33. Jefferson: McFarland, 2002.

This is an updated version of Harty’s chapter “The Arthurian Legends on Film: An Overview,” originally published in Cinema Arthuriana: Essays on Arthurian Film (New York: Garland Publishing, 1991), 3-28.

Harty, Kevin J. “The Grail on Film.” In The Grail, the Quest and the World of Arthur. Edited by Norris J. Lacy, 185-206. Woodbridge: D. S. Brewer, 2008.

Harty lists 28 films in alphabetical order that have clear representations of the Holy Grail. Each entry contains cast, credits, synopsis, commentary, and references to reviews and additional discussions. Harty avoids films with “grail” in the title, yet lacking any substantial representation of the Grail.

Harty, Kevin J. “Lights! Camelot! Action!–King Arthur on Film.” In King Arthur on Film: New Essays on Arthurian Cinema. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 5-37. Jefferson: McFarland, 1999.

Olton, Bert. Arthurian Legends on Film and Television. Jefferson, NC: McFarland Publishing, 2000.

Contains over 250 entries for interpretations of Arthurian legend on screen. Entries are arranged alphabetically with basic details, synopses, and commentary.

Salda, Michael N. “Arthurian Animation.” 2nd ed. The Camelot Project, 2005.

Contains 134 cartoons featuring Arthurian characters and legend. Titles arranged by release date and include author’s commentary.

Available on the Wayback Machine.

Tarpley, Fred. “King Arthur on Film.” In The Arthurian Myth of Quest and Magic: A Festschrift in Honor of Lavon B. Fulwiler. Edited by William E. Tanner, 117-128. Dallas: Caxton’s Modern Arts Press, 1993.

The first half of this paper is walk through of Harty’s 1992 paper “Teaching Arthurian Film” (see Teaching Tool section above) with Tarpley’s added commentary on the selected films. The second-half of the paper is a filmography of 24 Arthurian films in chronological order. Most have commentary from Tarpley.

Torregrossa, Michael A. “Merlin at the Multiplex: A Filmography of Merlin in Arthurian Film, Television and Videocassette 1920-1998.” Film & History CDROM Annual, 1999.

In this filmography, Torregrossa lists every movie and television show that features or even mentions Merlin. Works are grouped and sorted by release year. More importantly, Torregrossa has annotated each entry. Although conceding the list is likely incomplete, it does include 83 works between 1923 and 1998. The work was originally part of CDROM collection, but can be accessed through the link above.

Pedagogy

Each of these entries provides anecdotes and explores how teachers have incorporated Arthurian Legend from film and television into their medieval history and medievalism courses. Many of these works are refreshingly vulnerable, as the authors describe in detail their successes and failures with students.

Beatie, Bruce A. “Arthurian Films and Arthurian Texts: Problems of Reception and Comprehension.” Arthurian Interpretations 2 (1988): 65-78.

Beatie focuses on the use of Arthruian films in a “Faces of Camelot” undergraduate course where students watched 7 films, discussed the films and relevant readings, and received traditional lectures on Arthurian romance. Beatie chose this approach because “any real understanding of Arthurian literature, especially of its medieval texts, depends on an awareness of certain literary conventions with which college students today are rarely familiar, and on background knowledge of a period and a tradition which few students command.” The author found that the films provided media-oriented students with “a more immediate and profound means of access to the sometimes difficult works of Arthurian literary tradition.” The course and paper climax in the lecture and discussion of Excalibur (1981), which “was perhaps the most exciting event in my nearly thirty years of undergraduate teaching.”

Driver, Martha W. “‘Stond and Delyver’: Teaching the Medieval Movie.” In The Medieval Hero on Screen: Representations from Beowulf to Buffy. Edited by Martha W. Driver and Sid Ray, 211-216. Jefferson: McFarland, 2004.

Driver explores specific scenes in various movies useful for the classroom. Particular attention paid to Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975).

Koster, Josephine A. “’It’s Only a Model’: The Quest for King Arthur in Film and Literature Classes.” Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Teaching 16, no. 2 (2009): 97-109.

Harty, Kevin J. “Teaching Arthurian Film.” In Approaches to Teaching the Arthurian Tradition. Edited by Maureen Fries and Jeanie Watson, 147-150. New York: MLA, 1992.

Harty recognizes that when undergraduate students “show up for the first day of a semester-long course in Arthurian literature, few have read–and some have never heard of–Chrétien, Wolfram, Malory, Tennyson, Twain, or White.” As such, The author renamed a 14-week course to “King Arthur in Literature and Film.” The paper provides a complete syllabus and Harty narrates each week’s objectives with anecdotes from students’ reactions.

McClain, Lee Tobin. “Introducing Medieval Romance via Popular Films: Bringing the Other Closer.” Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Teaching 5, no. 2 (1997): 59-63.

McClain (previously Tobin–see below) describes employing medieval films in a romance course, using clips from Camelot (1967), Excalibur (1981), Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), and Casablanca (1942). This article has some remarkable insights, as McClain found “students are more comfortable with medieval stories we read after viewing the familiar fight scenes in the Arthurian films.” In addition, “When I began using Casablanca to represent modern romance, however, I soon realized that for students, 1942 is almost as long ago as 1492. Most of my students quickly lumped Casablanca together with the medieval period.” Finally, “students are media experts, much more so than I am, and using media frees students to educate the educator.” McClain goes on to describe learning new things from students with every lesson using this method.

Meuwese, Martine. “The Animation of Marginal Decorations in Monty Python and the Holy Grail.” Arthuriana 14, no. 4 (2004): 45-58.

Staines, David. “The Tradition of King Arthur: The Grail in Legend and Film.” Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Teaching 4, no. 1 (1993): 3-12.

The Holy Grail on Screen

The following works focus almost exclusively on the Holy Grail on screen.

Aronstein, Susan. “The Da Vinci Code and the Myth of History.” In The Holy Grail on Film: Essays on the Cinematic Quest, ed. Kevin J. Harty, 112-127. Jefferson: McFarland, 2015.

Aronstein examines more than 100 years’ worth of textual transmission that went into the eventual release of Ron Howard’s The Da Vinci Code (2006), which includes occultist books, obscure 1970s documentaries, the successful Holy Blood, Holy Grail pop history book (1982), and of course, Dan Brown’s 2003 novel. Aronstein focuses on how these books and the movie play with facts, “alternative facts,” interpretations, and loose (forced!) connections. Particularly useful is Aronstein’s analysis of the film’s flashback technique that “constantly reminds us that we have not been granted unmediated access to the past–that we are in fact watching a version of the past, not the past.”

Baragona, Alan. “Perceval of the Avant-Garde: Rohmer, Blank and von Trier.” In The Holy Grail on Film: Essays on the Cinematic Quest, ed. Kevin J. Harty, 50-66. Jefferson: McFarland, 2015.

Brown, Christine and Lynne C. Boughton. “The Grail Quest as Illumination.” Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 9, no. 1/2 (1997): 39-62.

Brown and Boughton examine the history and development of various Grail legends, concluding they “present man’s quest for transcendence and moral and spiritual renewal.” The author’s provide a lengthy exploration of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989) in this larger context.

Davidson, Roberta. “Now You Don’t See It, Now You Do: Recognizing the Grail as the Grail.” Studies in Medievalism 18 (2009): 188-202.

Elliott, Andrew B. R. “The Grail as Symbolic Quest in Tarkovsky’s Stalker.” In The Holy Grail on Film: Essays on the Cinematic Quest, ed. Kevin J. Harty, 187-201. Jefferson: McFarland, 2015.

Finke, Laurie A. and Martin B. Shichtman. “Looking Awry at the Grail: Mourning Becomes Modernity.” In Cinematic Illuminations: The Middle Ages on Film, 245-287. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 2010.

Harty, Kevin J. “Arnold Fanck’s 1926 Film Der Heilige Berg and the Nazi Quest for the Holy Grail.” In Romance and Rhetoric: Essays in Honour of Dhira B. Mahoney. Edited by Georgiana Donavin and Anita Obermeier, 223-233. Turnhout: Brepols, 2010.

Harty explores the 1926 German silent film Der Heilige Berg (The Holy Mountain) and “its association with the Nazi version of the legend of the Holy Grail.”

Harty, Kevin J., ed. The Holy Grail on Film: Essays on the Cinematic Quest. Jefferson: McFarland, 2015.

Harty, Kevin J. “Holy Grail, Silent Grail.” In The Holy Grail on Film: Essays on the Cinematic Quest, ed. Kevin J. Harty, 7-20. Jefferson: McFarland, 2015.

Harty surveys the production and reception of silent films featuring the Holy Grail–Parsifal (1904), Sir Galahad of Twilight (1914), The Grail (1915), The Knights of the Square Table (1917), The Light in the Dark (1922), and finally, Der Heilige Berg (1926). Harty provides detailed plot synopses for several of these films, as they are now rare and obscure. Given the breadth of films covered, the intentions vary from promoting the Boy Scouts to (un)wittingly promoting ideals of National Socialism. Thus, Harty’s conclusion is apt–“The silent cinematic Quest for the Holy Grail then offers a rich and varied legacy with an unintended, and more than unfortunate frame: the seeds and eventual imprint of the National Socialist agenda.”

See Harty’s “The Knights of the Square Table” (1994) and “Arnold Fanck’s 1926 Film Der Heilige Berg” (2010) for more detailed analysis of individual films.

Marshall, David W. “Holy Grail, Schlocky Grail.” In The Holy Grail on Film: Essays on the Cinematic Quest, ed. Kevin J. Harty, 215-231. Jefferson: McFarland, 2015.

Jesson, James. “Percival in Cooperstown: Arthurian Legend, Basebal Mythology and the Mediated Quest in Barry Levinson’s The Natural.” In The Holy Grail on Film: Essays on the Cinematic Quest, ed. Kevin J. Harty, 128-142. Jefferson: McFarland, 2015.

Miyares, J. Rubén Valdés. “The Cinematic Sign of the Grail.” Studies in Medievalism 21 (2012): 145-160.

Miyares explores the different ways in which films have represented the grail including an actual cup, a sword, or an intangible truth. In the end, Miyares believes that even when a film is blunt about its meaning of a grail depiction, it is impossible for the viewer to avoid finding different meanings.

Neufeld, Christine M. “‘Lovely Filth’: Monty Python and the Matter of the Holy Grail.” In The Holy Grail on Film: Essays on the Cinematic Quest, ed. Kevin J. Harty, 81-97. Jefferson: McFarland, 2015.

Schichtman, Martin B. “Whom Does the Grail Serve? Wagner, Spielberg, and the Issue of Jewish Appropriation.” In The Arthurian Revival: Essays on Form, Tradition, and Transformation. Edited by Debra N. Mancoff, 283-297. New York: Garland, 1992.

Staines, David. “The Tradition of King Arthur: The Grail in Legend and Film.” Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Teaching 1, no. 2 (1990): 3-12.

Sullivan, Joseph M. “A Son, His Father, Some Nazis and the Grail: Lucas and Spielberg’s Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.” In The Holy Grail on Film: Essays on the Cinematic Quest, ed. Kevin J. Harty, 158-172. Jefferson: McFarland, 2015.

Whetter, K. S. “The Silver Chalice: The Once and Future Grail.” In The Holy Grail on Film: Essays on the Cinematic Quest, ed. Kevin J. Harty, 21-36. Jefferson: McFarland, 2015.

Williams, Linda. “Eric Rohmer and the Holy Grail.” Literature/Film Quarterly 11, no. 2 (April 1983): 71-82.

Williams explores the uniqueness of Eric Rohmer’s Perceval le Gallois (1978). The film is based on Chrétien de Troyes’s 12th-century Perceval: The Story of the Grail, a work that Rohmer translated into modern-French. Williams starts with a review of medieval text followed by lengthy, almost shot-by-shot analysis of Rohmer’s interpretation.

The Knights of the Round Table (dir. Richard Thorpe, 1953)

The following works focus almost exclusively on The Knights of the Round Table (1953).

Kelly, Kathleen Coyne. “Hollywood Simulacrum: The Knights of the Round Table (1953).” Exemplaria 19, no. 2 (2007): 270-289.

Stubbs, Jonathan. “Hollywood’s Middle Ages: The Development of Knights of the Round Table and Ivanhoe, 1935–53.” Exemplaria 21, no. 4 (2009): 398-417.

Sullivan, Joseph M. “MGM’s 1953 Knights of the Round Table in its Manuscript Context.” Arthiriana 14, no. 3 (2004): 53-68.

Monty Python and the Holy Grail (dir. Terry Gilliam, 1975)

Each of these entries focuses almost exclusively on Terry Gilliam’s Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), but the movie comes up often in scholarship on Arthurian film.

Bartlett, Robert. “Now for Something Completely Different: Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975).” In The Middle Ages and the Movies: Eight Key Films, 77-104. London: Reaktion Books, 2022.

Burde, Mark. “Monty Python’s Medieval Masterpiece.” In Arthurian Yearbook. Volume 3. Edited by Keith Busy, 3-20. New York: Garland, 1993.

Burns, E. Jane. “Nostalgia Isn’t What It Used To Be: The Middle Ages in Literature and Film.” In Shadows of the Magic Lamp: Fantasy and Science Fiction in Film. Edited by George Slusser and Eric S. Rabkin, 86-97. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1985.

Burns explores the seemingly fresh return to nostalgia in filmmakers’ obsession with the Middle Ages during the 1970s and 1980s, focusing predominately on Arthurian films. Throughout the article, Burns turns to John Milton’s concern over “false romanticism” found in what has survived of King Arthur’s history. Burns believes Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975) “casts a dark shadow over any attempt, filmic or literary, to glorify the brutal merciless of people in the Middle Ages.” In addition, “it is difficult for anyone to read Tennyson’s Idylls of the King with unrestrained rapture, or to plunge headlong into the fanciful world of Malory’s Morte.” Because of Monty Python, “nostalgia isn’t what it used to be.”

Cleese, John. Graham Chapman, Terry Gilliam, Eric Idle, Terry Jones, and Michael Palin. Monty Python and the Holy Grail: Screenplay. 1977; York: Methuen, 2002.

Day, David D. “Monty Python and the Medieval Other.” In Cinema Arthuriana: Essays on Arthurian Film. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 83-92. New York: Garland Publishing, 1991.

Day, David D. “Monty Python and the Holy Grail: Madness with a Definite Method.” In Cinema Arthuriana: Twenty Essays. Revised ed. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 127-135. Jefferson: McFarland, 2002.

Hoffman, Donald L. “Not Dead Yet: Monty Python and the Holy Grail in the Twenty-first Century.” In Cinema Arthuriana: Twenty Essays. Revised ed. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 136-148. Jefferson: McFarland, 2002.

Holte, Jim. “’And Now for Something Completely Different’: Pythonic Arthuriana and the Matter of Britain.” In The Cinema of Terry Gilliam: It’s a Mad World. Edited by Jeff Birkenstein, Anna Froula, and Karen Randell, 42-53. London: Wallflower Press, 2013.

Housel, Rebecca. “Monty Python and the Holy Grail: Philosophy, Gender, and Society.” In Monty Python and Philosophy: Nudge Nudge, Think Think! Edited by Gary L. Hardcastle and George A. Reisch, 83-92. Chicago: Open Court, 2006.

Koster, Josephine A. “‘It’s Only a Model’: The Quest for King Arthur in Film and Literature Classes,” Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Teaching 16.2 (2009): 97-109.

Larsen, Darl. A Book about the Film Monty Python and the Holy Grail. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015.

Levy, Brian and Lesley Coote. “The Subversion of Medievalism in Lancelot du lac and Monty Python and the Holy Grail.” Studies in Medievalism 13 (2005): 99-126.

Excalibur (dir. John Boorman, 1981)

Each of these entries focuses almost exclusively on John Boorman’s Excalibur (1981), but the movie comes up often in scholarship on Arthurian film.

Chai-Elsholz, Raeleen and Jean-Marc Elsholz. “John Boorman’s Excalibur and the Irrigating Light of the Grail.” In The Holy Grail on Film: Essays on the Cinematic Quest, ed. Kevin J. Harty, 98-111. Jefferson: McFarland, 2015.

Clegg, Cyndia. “The Problem of Realizing Medieval Romance in Film: John Boorman’s Excalibur.” In Shadows of the Magic Lamp: Fantasy and Science Fiction in Film. Edited by George Slusser and Eric S. Rabkin, 98-111. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1985.

Clegg questions whether Excalibur (1981) “affords the audience an imaginative experience consistent with that of reading medieval romance.” Clegg states plainly on the second page that “the power of words creates possibilities which exist only in words.” Thus, you can see where the author is going with this piece. Still, Clegg examines “the power of reality in the image” and finds Excalibur wanting, but this also exposes “the difficult problem of presenting medieval romance in film.” The article includes detailed analysis of multiple scenes in the film.

Lacy, Norris J. “Mythopeia in Excalibur.” In Cinema Arthuriana: Twenty Essays. Revised ed. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 34-43. Jefferson: McFarland, 2002.

This is an updated version of the chapter “Mythopeia in Excalibur,” originally published in Cinema Arthuriana: Essays on Arthurian Film (New York: Garland Publishing, 1991), 121-134.

Lifshitz, Felice. “Destructive Dominae: Women and Vengeance in Medievalist Films.” Studies in Medievalism 21 (2012): 161-190.

Lifshitz provides a deep analysis of “violently destructive, vengeful dominae (ruling women, or female lords/domini)” in Die Nibelungen (1924) and Excalibur (1981). The two films use source material that experienced similar dissemination over the centuries. More to the point, the films are also “examples of anti-feminist work that emerged in reaction to specific feminist movements in twentieth-century Europe.” Lifshitz explores this history and the medievalism of the films in detail.

Purdon, Liam O., and Robert Blanch. “Hollywood’s Myopic Medievalism: Excalibur and Malory’s Morte d’Arthur.” In Popular Medievalism: Traditions. Edited by Sally K. Slocum, 156-161. Bowling Green: Bowling Green State University Press, 1992.

Shichtman, Martin B. “Hollywood’s Weston: The Grail Myth in Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now and John Boorman’s Excalibur.” In The Grail: A Casebook. Edited by Chira B. Mahoney, 561-573. New York: Garland Publishing, 2000.

Wakeman, Ray. “Excalibur: Film Reception and Political Distance.” In Politics in German Literature: Essays in Memory of Frank G. Ryder. Edited by Beth Bjorklund and Mark E. Cory, 166-176. Columbia: Camden House, 1998.

Whitaker, Muriel. “Fire, Water, Rock: Elements of Setting in John Boorman’s Excalibur and Steve Barron’s Merlin.” In Cinema Arthuriana: Twenty Essays. Revised ed. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 44-53. Jefferson: McFarland, 2002.

This is an updated version of the chapter “Fire, Water, Rock: Elements of Setting in Excalibur,” originally published in Cinema Arthuriana: Essays on Arthurian Film (New York: Garland Publishing, 1991), 135-143.

Parsifal (dir. Hans-Jürgen Syberberg, 1982)

Kleis, John Christopher. “The Arthurian Dilemma: Faith and Works in Syberberg’s Parsifal.” In King Arthur on Film: New Essays on Arthurian Cinema. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 109-122. Jefferson: McFarland, 1999.

Müller, Ulrich. “Blank, Syberberg, and the German Arthurian Tradition.” Translated by Julie Giffin. In Cinema Arthuriana: Twenty Essays. Revised ed. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 177-184. Jefferson: McFarland, 2002.

This chapter is also available in Cinema Arthuriana: Essays on Arthurian Film (New York: Garland Publishing, 1991), 157-168.

Sherman, Jon. “Hans-Jürgen Syberberg’s Parsifal: Remystifying Kundry.” In The Holy Grail on Film: Essays on the Cinematic Quest, ed. Kevin J. Harty, 67-80. Jefferson: McFarland, 2015.

The Fisher King (dir. Terry Gilliam, 1991)

Each of these entries focuses almost exclusively on Terry Gilliam’s The Fisher King (1991).

Blanch, Robert J. “The Fisher King in Gotham: New Age Spiritualism Meets the Grail Legend.” In King Arthur on Film: New Essays on Arthurian Cinema. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 123-139. Jefferson: McFarland, 1999.

Furby, Jacqueline. “The Fissure King: Terry Gilliam’s Psychotic Fantasy Worlds.” In The Cinema of Terry Gilliam: It’s a Mad World. Edited by Jeff Birkenstein, Anna Froula, and Karen Randell, 79-91. London: Wallflower Press, 2013.

LaGravenese, Richard. The Fisher King: The Book of the Film. New York: Applause, 1991.

Osberg, Richard H. “Pages Torn from the Book: Narrative Disintegration in Gilliam’s The Fisher King.” Studies in Medievalism 7 (1995): 194-224.

Rushton, Cory James. “Terry Gilliam’s The Fisher King.” In The Holy Grail on Film: Essays on the Cinematic Quest, ed. Kevin J. Harty, 143-157. Jefferson: McFarland, 2015.

Stenberg, Doug. “Tom’s a-cold: Transformation and Redemption in King Lear and The Fisher King.” Literature/Film Quarterly 22, no. 3 (1994): 160-169.

Stukator, Angela. “‘Soft Males,’ ‘Flying Boys,’ and ‘White Knights’: New Masculinity in The Fisher King.” Literature/Film Quarterly 25, no. 3 (1997): 214-212.

King Arthur (dir. Antoine Fuqua, 2004)

Each of these entries focuses almost exclusively on Antoine Fuqua’s King Arthur (2004). Some scholars refer to it as “Jerry Bruckheimer’s King Arthur,” the producer.

Blanton, Virginia. “‘Don’t Worry, I Won’t Let Them Rape You’: Guinevere’s Agency in Jerry Bruckheimer’s King Arthur.” Arthuriana 15, no. 3 (2005): 91–111.

Blanton analyzes the depiction and promotion of Guinevere in King Arthur (2004) against the backdrop of American culture that increasingly wanted to see women featured prominently in action movies. Blanton describes the depiction as “a complicated hybrid of femininity and masculinity, one that illustrates contemporary anxieties about strong women, women in warfare, women who want to be equal to men on all playing fields.”

Houswitschka, Cristoph. “A Postcolonial View on King Arthur (2004) and Nomad (2005).” Studia Litteraria Universitatis Iagellonicae Cracoviensis 10 (2015): 107-120.

Houswitschka compares and contrasts King Arthur (2004) and the Kazakhstani film Nomad (2005), finding similarities between characters, themes, and plot points. Each film serves “ambiguous ideological purposes by defining a hostile other.” The author points out that many medieval films “convey hidden or silent assumptions about the politics” based on when the film was made, not the period it was about. Thus, “this is what makes many films about the Middles Ages difficult to watch after a few decades,” as the original ideology of the characters are lost. In the case of King Arthur, the film “‘modernises’ the Middle Ages by constructing a transcultural nation that embraces hybridity and cosmopolitanism.”

Jewers, Caroline. “Mission Historical, or ‘[T]here Were a Hell of a Lot of Knights’: Ethnicity and Alterity in Jerry Bruckheimer’s King Arthur.” In Race, Class and Gender in “Medieval” Cinema. Edited by Lynn T. Ramey and Tison Pugh, 91-106. New York: Palgrave, 2007.

Matthews, John. “A Knightly Endeavor: The Making of Jerry Bruckheimer’s King Arthur.” Arthuriana 14, no. 3 (2004): 112-115.

Matthews candidly recounts the making of the film.

Matthews, John. “An Interview with David Franzoni.” Arthuriana 14, no. 3 (2004): 115-120.

Matthews interviews David Franzoni, screenwriter for Gladiator, Amista, and King Arthur. They focus on Arthurian legend and Franzoni’s method for writing the screenplay. As Matthews puts it, “Here was an opportunity for the writer of the film to put his own case directly to the Arthurian community and to explain the thinking behind some of the decisions that went into finished work.”

Shippey, Tom. “Fuqua’s King Arthur: More Myth-making in America.” Exemplaria 19, no. 2 (2007): 310-326.

Sullivan, Joseph M. “Cinema Arthuriana without Malory?: The International Reception of Fuqua, Franzoni, and Bruckheimer’s King Arthur (2004).” Arthuriana 17, no. 2 (2007): 85-105.

The Green Knight (dir. David Lowery, 2021)

Each of these entries focuses almost exclusively on David Lowery’s The Green Knight (2021).

Abrahamson, Megan B. “Spectacle and Cyclicality in The Green Knight.” The Year’s Work in Medievalism 37 (2025): 35-41.

Brown, Rob. “The Place of the Middle in The Green Knight.” The Year’s Work in Medievalism 37 (2025): 16-25.

Crofton, Melissa. “Medieval Poem versus 21st Century Film: Why Choose One When You Can Have Both?” South Atlantic Review 88.2-3 (Summer/Fall 2023): 1-5.

Crofton, Melissa. “‘You Are No Knight’: David Lowery Rivals a Medieval Poem in The Green Knight.” South Atlantic Review 88.2-3 (Summer/Fall 2023): 41-60.

Doucet, Annie. “Essel and the Lady: Troubadourian Duality in David Lowery’s The Green Knight.” The Year’s Work in Medievalism 37 (2025): 48-56.

Forni, Kathleen. “Lowery’s The Green Knight: Honor Reconsidered.” South Atlantic Review 88.2-3 (Summer/Fall 2023): 61-77.

Gorgievski, Sandra, and Martine Yvernault, eds. Agrégation anglais: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Anonyme (c. 1400) et The Green Knight, Film de David Lowery (2021). Paris: Ellipses, 2023.

Harty, Kevin J. “David Lowery’s The Green Knight (2021): Authenticity and Accuracy, Historicons and Easter Eggs.” In Cinema Medievalia: New Essays on the Reel Middle Ages. Edited by Kevin J. Harty and Scott Manning, 343-360. Jefferson: McFarland, 2024.

Harty, Kevin J. “Notes Towards a Close Reading of David Lowery’s 2021 Film The Green Knight.” Journal of the International Arthurian Society 10.1 (2022): 29–51.

Harty, Kevin J. “Spoiling the Sport, Upping the Ante, and Calling His Bluff: Why St. Winifred Appears in David Lowery’s 2021 Film The Green Knight.” Studies in Medievalism 32 (2023): 11–19.

Highley, Sarah L. “David Lowery’s ‘The Green Knight’: An Ecocinematic Dialogue between Film and Poem.” Medieval Ecocriticisms 2 (2022): 53–87.

Keane, Chelsea. “‘It’s Definitely Green-ish’: Co-Disciplinarity, Verdigris, and Vegetal Time in David Lowery’s 2021 The Green Knight.” The Year’s Work in Medievalism 37 (2025): 1-7.

Martin, Molly. “St. Winifred’s Ghost and the Imagined Medieval of The Green Knight.” The Year’s Work in Medievalism 37 (2005): 57-67.

Martin, Rachel. “‘A New Tale?’: The Welsh in David Lowery’s The Green Knight.” South Atlantic Review 88.2-3 (Summer/Fall 2023): 23-40.

Maxwell, Drew. “‘Is this Really All There Is?’: The Role and Representation of Women in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and David Lowery’s The Green Knight.” South Atlantic Review 88.2-3 (Summer/Fall 2023): 78-94.

Narayanan, Tirumular (Drew). “‘Why Is He Indian?’ Missed Opportunities for Discussing Race in David Lowery’s The Green Knight (2021).” Arthuriana 33 (Fall 2023): 36–59.

Price, Emily A. “‘Green Shall Spread Over All’: Transference and The Green Knight as Eco-Horror.” The Year’s Work in Medievalism 37 (2025): 42-47.

Pugh, Tison. “Seminal Semiotics and Pornographic Displeasures in David Lowery’s The Green Knight (2021).” Arthuriana 32 (Fall 2022): 40–57.

Sprouse, Sarah H. “Interior and Exterior Journeys: Simulacrum in The Green Knight (2021).” The Year’s Work in Medievalism 37 (2025): 29-34.

Taylor, A. Arwen. “Like Nothing: Lingua and The Green Knight.” The Year’s Work in Medievalism 37 (2025): 8-15.

Wahnsiedler, Andrew. “‘I Will Tell You a New Tale’: The Evolving Gawain Myth and Its Political Implications.” South Atlantic Review 88.2-3 (Summer/Fall 2023): 6-21.

Wolf, Michelle. “‘A Knight Should Know Better’: Sexual Integrity and the Madonna-Whore Dichotomy in Lowery’s The Green Knight. South Atlantic Review 88.2-3 (Summer/Fall 2023): 95-105.

Looking for Arthur in All the Wrong Places

Kevin J. Harty has remarked on several occasions that “perhaps in our search for a cinematic translation of the Arthurian myth, we have been looking in all the wrong places.” The following entries focus on films that are not overtly about Arthurian myth, but they still manage to “surprise and tease us—they attest the continuing viability of the Arthurian legend.”

Edrei, Shawn. “Once and Future: Adaptations of Camelot in Non-Arthurian Television Narratives.” Mediascape (Fall 2014).

Finke, Laurie A. and Martin B. Shichtman. “The Waterboy and Swamp Chivalry: A Grail Knight for American Teens.” In The Holy Grail on Film: Essays on the Cinematic Quest, ed. Kevin J. Harty, 202-214. Jefferson: McFarland, 2015.

Gil, Steven. “Sword and Science: Science-Fiction Interpretations of Medieval Arthurian Literature and Legend in Stargate SG-1.” In Fantasy and Science-Fiction Medievalisms: From Isaac Asimov to A Game of Thrones. Edited by Helen Young, 141-160. Amherst: Cambria Press, 2015.

Harty, Kevin J. “Looking for Arthur in All the Wrong Places: A Note on M. Night Shyamalan’s The Sixth Sense.” Arthuriana 10, no. 4 (2000): 57-62.

Harty explores how The Sixth Sense (1999) utilizes plot, themes, and characters that mimic Arthurian legend.

Kleis, John Christopher. “Tortilla Flat and the Arthurian View.” In Cinema Arthuriana: Twenty Essays. Revised ed. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 71-79. Jefferson: McFarland, 2002.

Manning, Scott. “Arthurian Legend and the Death of Optimus Prime in Transformers: The Movie (1986).” Studies in Medievalism XXXIV (2025): 192-212.

Scheuer, Hans Jürgen. “Arthurian Myth and Cinematic Horror: M. Night Shyamalan’s The Sixth Sense.” In The Medieval Motion Picture: The Politics of Adaptation. Edited by Andrew James Johnston, Margitta Rouse, and Philipp Hinz, 171-191. New York: Palgrave, 2014.

Scheuer reads The Sixth Sense as a “fully valid film adaptation of the Arthurian legend” in “conjunction with medieval discourses on the nature of the sixth sense, discourses that previous commentators of the movie neglected entirely. Exposing the film’s underlying Arthurian narrative structures will show that Shyamalan’s concept of the sixth sense is also a full-fledged adaptation of a premodern notion of image perception underpinning the imagination of Arthurian romance.”

Shaham, Inbar. “Ancient Myths in Contemporary Cinema: Oedipus Rex and Perceval the Knight of the Holy Grail in Pulp Fiction and The Sixth Sense.” Mythlore 28, no. 1 (2009): 87-101.

Sturtevant, Paul B. “A Grail or a Mirage? Searching the Wasteland of The Road Warrior.” In The Holy Grail on Film: Essays on the Cinematic Quest, ed. Kevin J. Harty, 173-186. Jefferson: McFarland, 2015.

Miscellaneous

These are works that didn’t fit nicely into any of the categories above or that I simply haven’t read yet to classify appropriately.

Aronstein, Susan. Hollywood Knights: Arthurian Cinema and the Politics of Nostalgia. New York: Palgrave, 2005.

Aronstein, Susan. “‘Not Exactly a Knight’: Arthurian Narrative and Recuperative Politics in the Indiana Jones Trilogy.” Cinema Journal 34, no. 4 (1995): 3–30.

With the completion of the Grail Quest in The Last Crusade (1989), Aronstein analyzes the original Indiana Jones trilogy as a modern retelling of Arthurian legend with “tales of knighthood, modernizations of medieval chivalric romances in which America stands in for the Arthurian court, the Third World becomes the forest of adventure, and the Nazis or Thuggees function as hostile knights to be defeated in an effort to recuperate and reaffirm America’s cultural destiny.”

Aronstein, Susan. “Romancing the Cold War: America’s Atomic Narrative Gets Medieval.” Arthuriana 29, no. 2 (2019): 86-101.

Examines The Adventures of Sir Galahad (1949) serial in the context of the evolving Cold War.

Aronstein, Susan and Nancy Coiner. “Twice Knightly: Democratizing the Middle Ages for Middle-Class America.” Studies in Medievalism 6 (1994): 185–211.

Beatie, Bruce A. “The Broken Quest: The ‘Perceval’ Romanances of Chrétien de Troyes and Eric Rohmer.” In The Arthurian Revival: Essays on Form, Tradition, and Transformation. Edited by Debra N. Mancoff, 248-265. New York: Garland, 1992.

Blanch, Robert J. “George Romero’s Knightriders: A Contemporary Arthurian Romance.” Quondam et Futurus 1, no. 4 (1991): 61-69.

Blanch explores the origins and medievalisms of Knightriders (1981).

Blanch, Robert J. and Julian N. Wasserman. “Fear of Flyting: The Absence of Internal Tension in The Sword of the Valiant and First Knight.” Arthuriana 10, no. 4 (2000): 15-32.

Blanch and Wasserman lambastes The Sword of the Valiant (1984) and First Knight (1995) for their lack of internal tension, which is prevalent in the medieval source material. With this approach, the authors argue that the filmmakers made their movies easy targets for critics. They review the source material in detail in hopes of increasing appreciation for the medieval works.

Bradford, Clare and Rebecca Hutton. “Female Protagonists in Arthurian Television for the Young: Gendering Camelot.” In The Middle Ages in Popular Culture: Medievalism and Genre. Edited by Helen Young, 11-34. Amherst: Cambria Press, 2015.

Bradford and Hutton analyze the use of female protagonists in the television series The Legend of Prince Valiant (1991-1994) and Sir Gadabout: The Worst Knight in the Land (2002-2003), and the made-for-television film Avalon High (2010). These works challenge the traditional gender roles among of in Arthurian Legend. The authors then compare these works to Authrian fiction for young adults, finding that male-centric stories still dominate the fields.

Callahan, Leslie Abend. “Perceval le Gallois: Eric Rohmer’s Vision of the Middle Ages.” Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies 29, no. 3-4 (1999): 46-53.

Codell, Julie F. Codell. “Decapitation and Deconstruction: The Body of the Hero in Robert Bresson’s Lancelot du Lac.” In The Arthurian Revival: Essays on Form, Tradition, and Transformation. Edited by Debra N. Mancoff, 266-282. New York: Garland, 1992.

Dahm, Murray. “King Arthur: Medieval Warfare in film.” Medieval Warfare 6, no. 2 (2016): 49-50.

Dahm, Murray. “King Arthur II: Medieval Warfare in film.” Medieval Warfare 6, no. 3 (2016): 53-55.

Davidson, Roberta. “The Reel Arthur: Politics and Truth Claims in Camelot, Excalibur, and King Arthur.” Arthuriana (2007): 62-84.

Davidson explores how filmmakers employ King Arthur explicitly and implicitly for their own political agendas as a platform hope. The author finds that “the figure of Arthur invites us to use him as a model for who we want our leaders to be and what we want them to represent,” because of “his lack of absolute perfection.” It is the lack of perfection that somehow makes us believe his ideal–or whatever ideal we associate with him–is somehow attainable.

de Weever, Jackqueline. “Morgan and the Problem of Incest.” In Cinema Arthuriana: Twenty Essays. Revised ed. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 54-63. Jefferson: McFarland, 2002.

This chapter is also available in Cinema Arthuriana: Essays on Arthurian Film (New York: Garland Publishing, 1991), 145-156.

Elliott, Andrew B. R. “The Charm of the (Re)making: Problems of Arthurian Television Serialization.” Arthuriana 21, no. 4 (2011): 53-67.

Elmes, Melissa Ridley. “Episodic Arthur: Merlin, Camelot, and the Visual Modernization of the Medieval Literary Romance Tradition.” In The Middle Ages on Television: Critical Essays. Edited by Meriem Pagès and Karolyn Kinane, 99-121. Jefferson: McFarland, 2015.

Elmes focuses on BBC’s Merlin (2008-2012) and Starz’s Camelot (2011), arguing that “television is a medium more compatible with the medieval romance tradition that first gave rise to our contemporary ideas of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table.” In addition, “the episodic nature of television allows modern audiences to experience a much more authentic representation of these stories as they were circulated and constructed in the Middle Ages,” much more so than cinema.

Everett, William A. “King Arthur in Popular Musical Theatre and Musical Film.” In King Arthur in Music. Edited by Richard Barber, 145-160. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2002.

Farrell, Eleanor M. “King Arthur ‘Lite’: Dilution of Mythic Elements in Arthurian Film.” Mythlore 22, no. 3 (1999): 55-65.

Feinstein, Sandy. “Are You Kidding? King Arthur and the Knights of Justice.” In The Middle Ages on Television: Critical Essays. Edited by Meriem Pagès and Karolyn Kinane, 122-138. Jefferson: McFarland, 2015.

In examining the animated series King Arthur and the Knights of Justice (1992-1993), Feinstein argues “Arthurian motifs are ‘remediated’ in the serial, the term used by Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin to refer to ‘the representation of on medium in another,’” which “works actively to involve the audience.”

Finke, Laurie A. and Martin B. Shichtman. “Inner-City Chivalry in Gil Junger’s Black Knight: A South Central Yankee in King Leo’s Court.” In Race, Class and Gender in “Medieval” Cinema. Edited by Lynn T. Ramey and Tison Pugh, 107-121. New York: Palgrave, 2007.

Foster, Tara. “Arthur and Guenièvre: The Royal Couple of Kaamelott.” In The Middle Ages on Television: Critical Essays. Edited by Meriem Pagès and Karolyn Kinane, 174-196. Jefferson: McFarland, 2015.

Foster focuses on the presentations of Guenièvre and other female figures in Kaamelott (2005-2009) “using Maureen Fries’s categorization of Authurian women as a framework, looking at ways in which the show subverts a number of the ‘already-givens’ of various female characters and carves a space for female agency within its version of King Arthur’s world.”

Fries, Maureen. “How to Handle a Woman, or Morgan at the Movies.” In King Arthur on Film: New Essays on Arthurian Cinema. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 67-80. Jefferson: McFarland, 1999.

George, Michael W. “Television’s Male Gaze: The Male Perspective in TNT’s Mists of Avalon.” In The Middle Ages on Television: Critical Essays. Edited by Meriem Pagès and Karolyn Kinane, 141-157. Jefferson: McFarland, 2015.

George argues that The Mists of Avalon (2001) “masquerades as a miniseries with a female perspective, participating in and perpetuating a tradition of androcentric television medievalism,” which was “an early harbinger of the proliferating trend.”

Gorgievski, Sandra. “The Arthurian Legend in the Cinema: Myth or History?” In The Middle Ages after the Middle Ages in the English-Speaking World. Edited by Marie-Françoise Alamichel and Derek Brewer, 153-166. Woodbridge: D. S. Brewer, 1997.

Gorgievski, Sandra. “From Stage to Screen: The Dramatic Compulsion in French Cinema and Denis Llorca’s Les Chevaliers de la table ronde (1990).” In Cinema Arthuriana: Twenty Essays. Revised ed. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 163-177. Jefferson: McFarland, 2002.

Gossedge, Rob. “The Sword in the Stone: American Translatio and Disney’s Antimedievalism.” In The Disney Middle Ages: A Fairy-tale and Fantasy Past. Edited by Tison Pugh and Susan Aronsten, 115-131. New York: Palgrave, 2012.

Gossedge finds The Sword in the Stone (1963) unique among Disney’s animated films in that it “could not erase the massive corpus of Arthurian myth in favor of its own clean-cut, trivialized, and rigorously ‘innocent’ narrative.” The author examines the film against its sources of T. H. White and the various incarnations of White’s original work via radio, stage, screen, and even by later Arthurian texts, revealing how “the film’s paratexts, rather than White’s novel itself, seem to have dictated much of its cultural production and reception.” Gossedge concludes that the movie “both appropriates and rejects an English Arthurian story in favor of a thinly worked idyll of a boy’s unexpected, unwanted, and unexplained rise to kingship,” making it one of the least Arthurian films produced.

Grimbert, Joan Tasker. “Distancing Techniques in Chrétien de Troyes’s Li Contes del Graal and Eric Rohmer’s Perceval le Gallois.” Arthuriana 10, no. 4 (2000): 33-44.

Grimbert, Joan Tasker. “Truffaut’s La Femme d’à côté (1981): Attenuating a Romantic Archetype–Tristan and Iseult?” In King Arthur on Film: New Essays on Arthurian Cinema. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 183-201. Jefferson: McFarland, 1999.

Grimbert, Joan Tasker and Robert Smarz. “Fable and Poésie in Cocteau’s L’Éternel Retour (1943).” In Cinema Arthuriana: Twenty Essays. Revised ed. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 220-234. Jefferson: McFarland, 2002.

Grimbert, Joan Tasker. “Lancelot du lac: Robert Bresson’s Arthurian Realism.” In The Holy Grail on Film: Essays on the Cinematic Quest, ed. Kevin J. Harty, 37-49. Jefferson: McFarland, 2015.

Grimbert, Joan Tasker. “Tristan in Film.” Arthuriana 29, no. 2 (2019): 47-63.

Harty, Kevin J., ed. Cinema Arthuriana: Twenty Essays. Rev. ed. Jefferson: McFarland, 2002.

Harty, Kevin J. “James Bond, A Grifter, A Video Avatar, and a Shark Walk into King Arthur’s Court: The Ever-Expanding Canon of Cinema Arthuriana.” Arthuriana 30, no. 2 (2020): 89-121.

Harty, Kevin J. “Film.” In The New Arthurian Encyclopedia. Edited by Norris J. Lacy, 152-155. New York: Garland, 1996.

Harty, Kevin J. “King Arthur Goes to War (Singing, Dancing, and Cracking Jokes): Marcel Varnel’s 1942 Film King Arthur Was A Gentleman.” Arthuriana 14, no. 4 (2004): 17-25.

Harty, Kevin J., ed. King Arthur on Film: New Essays on Arthurian Cinema. Jefferson: McFardland, 1999.

Harty, Kevin J. “The Knights of the Square Table: The Boy Scouts and Thomas Edison Make an Arthurian Film.” Arthuriana 4 (1994): 313-23.

Harty, Kevin J. “Parsifal and Perceval on Film: The Reel Life of a Grail Knight.” In Percevalz/Parzival: A Casebook. Edited by Arthur Groos and Norris J. Lacy, 301-112. New York: Routledge, 2002.

Harty, Kevin J. “Shirley Temple and the Guys and Dolls of the Round Table.” In The Medieval Hero on Screen: Representations from Beowulf to Buffy. Edited by Martha W. Driver and Sid Ray, 57-72. Jefferson: McFarland, 2004.

Harty examines the Arthurian subplot in Little Miss Marker (1934). This was an addition to the original short story of the same name and further remakes of the film do not utilize the subplot.

Haydock, Nickolas A. “Arthurian Melodrama, Chaucerian Spectacle, and the Waywardness of Cinematic Pastiche in First Knight and A Knight’s Tale.” Studies in Medievalism 12 (2002): 5-38.

Haydock explores how First Knight (1995) and A Knight’s Tale (2001) “flaunt anachronism, design not to render faithfully their respective sources in Malory or Chaucer, but rather appeal to cinematic imaginary about the Middle Ages, composed of bits and pieces drawn from film history and popular culture.”

Hildebrand, Kristina. “Knights in Space: The Arthur of Babylon 5 and Dr. Who.” In King Arthur in Popular Culture. Edited by Elizabeth S. Sklar and Donald L. Hoffman, 101-110. Jefferson: McFarland, 2002.

Hoffman, Donald L. “Queer as Folk.” Arthuriana 29, no. 2 (2019): 24-46.

Examines a more or less randomly chosen internet list of the “Ten Best Arthurian Films” to show that queerness rather broadly defined lurks (as is its wont) in the gaps, disruptions, and interstices of most Arthurian films.

Hoffman, Donald L. “Re-Framing Perceval.” Arthuriana 10, no. 4 (2000): 45-56.

Hoffman, Donald L. “Tristan la Blonde: Transformations of Tristan in Buñel’s Tristana.” In King Arthur on Film: New Essays on Arthurian Cinema. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 167-182. Jefferson: McFarland, 1999.

Howey, Ann F. “Father Doesn’t Know Best: Uther and Arthur in BBC’s Merlin.” The Year’s Work in Medievalism 30 (2015).

Jenkins, Jacqueline. “First Knights and Common Men: Masculinity in American Arthurian Film” In King Arthur on Film: New Essays on Arthurian Cinema. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 81-95. Jefferson: McFarland, 1999.

Kelly, Kathleen Coyne. “Monumentality and the Gaze in Jean Cocteau’s L’Éternal retour (1943).” Arthuriana 19, no. 3 (2009): 62-71.

Lacy, Norris J. “Arthurian Film and the Tyranny of Tradition.” Arthurian Interpretations 4 (1989): 75-85.

Lacy, Norris J. “The Documentary Arthur: Reflections of a Talking Head.” In King Arthur in Popular Culture. Edited by Elizabeth S. Sklar and Donald L. Hoffman, 77-86. Jefferson: McFarland, 2002.

Lacy, Norris J. “Lovespell and the Disinterpretation of a Legend.” Arthuriana 10, no. 4 (2000): 5-14.

Laity, K. A. “Medieval Community: Lessons from the Film Black Knight.” Latch: A Journal for the Study of the Literary Artifact in Theory, Culture, or History 1 (2008): 147-157.

López Mate, V. J. “The legacy of Excalibur: Neomedievalism and the Resemiotization of the Legend in Film and Television.” Guarecer. Revista Eletrónica De Estudos Medievais 8 (2025): 53–64.

Lupack, Alan. “From Kids as Galahad to Kid Galahad.” Arthuriana 29, no. 2 (2019): 102-114.

Lupack, Barbara Tepa. “Camelot on Camera: The Arthurian Legends and Children’s Film.” In Adapting the Arthurian Legends for Children: Essays on Arthurian Juvenilia. Edited by Barbara Tepa Lupack, 263-294. New York: Palgrave, 2004.

Lupack, Barbara Tepa. “A Connecticut Yankee at the Movies.” Arthuriana 29, no. 2 (2019): 64-85.

Examines the earliest silent and sound versions of Connecticut Yankee films.

Lupack, Barbara Tepa. “The Retreat from Camelot: Adapting Bernard Malamud’s The Natural to Film.” In Cinema Arthuriana: Twenty Essays. Revised ed. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 80-95. Jefferson: McFarland, 2002.

MacCurdy, Marian. “Bitch or Goddess: Polarized Images of Women in Arthurian Films and Literature.” Platte Valley Review 18 (1990): 3-24.

Meredith, Elysse T. “Gendering Morals, Magic and Medievalism in the BBC’s Merlin.” In The Middle Ages on Television: Critical Essays. Edited by Meriem Pagès and Karolyn Kinane, 158-173. Jefferson: McFarland, 2015.

Meredith’s essay examines the intersection of gender, magic, and morality within Merlin [2008-2012] in relation to its literary antecedents and contemporary British concerns.”

Miller, Barbara D. “‘Cinemagicians’: Movie Merlins of the 1980s and 1990s.” In King Arthur on Film: New Essays on Arthurian Cinema. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 141-166. Jefferson: McFarland, 1999.

Nickel, Helmut. “Arms and Armor in Arthurian Films.” In Cinema Arthuriana: Twenty Essays. Rev. ed. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 235-251. Jefferson: McFarland, 2002.

Nickel examines the accuracy of arms and armor depicted in Arthurian films. The author recognizes that given that the surviving sources were written hundreds of years after the supposed events, often appropriating technology from the time of writing, “the scriptwriter, the director, and the costume designer are free to choose a timespan of almost a thousand years, if their ambition would call for historical accuracy.” Nickel goes even further to point out that the legendary nature of Arthur would justify “any flight of fancy concerning costume and setting.” Nickel then examines film by film, critiquing the anachronisms.

Also published in Cinema Arthuriana: Essays on Arthurian Film (New York: Garland Publishing, 1991), 181-201.

Olton, Bert. “Was that in the Vulgate? Arthurian Legend in TV Film and Series Episodes.” In King Arthur in Popular Culture. Edited by Elizabeth S. Sklar and Donald L. Hoffman, 87-100. Jefferson: McFarland, 2002.

Osberg, Richard H. and Michael E. Crow. “Language Then and Language Now in Arthurian Film.” In King Arthur on Film: New Essays on Arthurian Cinema. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 39-66. Jefferson: McFarland, 1999.

Petrovskaia, Natalia I. “The Fool and the Wise Man: The Legacy of the Two Merlins in Modern Culture.” In The Legacy of Courtly Literature: From Medieval to Contemporary Culture. Edited by Deborah Nelson-Campbell and Rouben Cholakian, 173-203. New York: Palgrave, 2017.

Petrovskaia believes that incarnations of Merlin “can be categorized as either a guiding figure (wise man), or a person occupying a marginalized position in society, or indeed outside it (fool).” The author then explores literary and cinematic versions of Merlin through this model. The author also briefly explores how the model can expand to avatars of Merlin. For example, “the more ambiguous figure of Obi-Wan Kenobi can be analyzed as the ‘wise man’ Merlin (Episodes I–III), a guiding figure and advisor, and ‘fool’ Merlin (Episode IV), an eccentric outcast living on the edge, or perhaps even outside, society.”

Also useful as a general introduction to medievalism is Petrovskaia promotion and defense of studying modern interpretations of Merlin. The author argues persuasively that “our general perception of the common image of Merlin is guided by something other than the knowledge of medieval texts, and by something more than the classics that feature him.” More importantly, historians bemoan having access only to texts by and for intellectuals and elites, but “when venturing into the modern world, the temptation is accordingly to stick with the familiar field of action and avoid the vast unchartered territories of mass-market popular culture, although it is unclear why it is difficult to write a scholarly essay about, for instance, a computer game.” Petrovskaia argues that medievalists should use the same skills and experience honed for analyzing medieval texts to also focus on modern interpretations.

Salda, Michael N. Arthurian Animation: A Study of Cartoon Camelots on Film and Television. Jefferson: McFarland, 2013.

Salda, Michael N. “Arthurian Animation at Century’s End.” In King Arthur in Popular Culture. Edited by Elizabeth S. Sklar and Donald L. Hoffman, 111-121. Jefferson: McFarland, 2002.

Salda, Michael N. “‘What’s Up, Duke?’ A Brief History of Arthurian Animation.” In King Arthur on Film: New Essays on Arthurian Cinema. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 203-232. Jefferson: McFarland, 1999.

Salda, Michael N. “The Worst Arthurian Cartoon Ever.” Arthuriana 16, no. 2 (2006): 54-58.

Salda lambast’s Daffy Duck & Porky Pig Meet the Groovie Goolies (1972), a 1-hr cartoon that features Daffy’s attempt to direct his own Arthurian film. The movie has achieved Internet fame as being one of the worst cartoons, let alone a bad Arthurian cartoon. Salda reviews it in detail.

Schwam-Baird, Shira. “King Arthur in Hollywood: The Subversion of Tragedy in First Knight.” Medieval Perspectives 14 (1999): 202-213.

Schwam-Baird examines how “First Knight transforms the outlines of the Arthurian story as it has come down to the English-speaking public ever since Malory,” by “sidestepping the monumental tragedy of the downfall of Camelot.” Even allowing for the regular reshaping of the Arthruian story to suit contemporary needs, the author finds that “this particular recasting bears witness to an allergy to tragedy endemic in Hollywood.”

Semper, Philippa. “‘Camelot must come before all else’: Fantasy and Family in the BBC Merlin.” In Medieval Afterlives in Contemporary Culture. Edited by Gail Ashton, 115-123. London: Bloomsbury, 2015.

Sklar, Elizabeth S. “Twain for Teens: Young Yankees in Camelot.” In King Arthur on Film: New Essays on Arthurian Cinema. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 97-108. Jefferson: McFarland, 1999.

Snyder, Christopher A. “‘Who are the Britons?’: Questions of Ethnic and National Identity in Arthurian Films.” Arthuriana 29, no. 2 (2019): 6-23.

This essay looks at issues of national and ethnic identity raised by three Arthurian films: Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), King Arthur (2004), and The Last Legion (2007).

Torregrossa, Michael. “Merlin Goes to the Movies: The Changing Role of Merin in Cinema Arthuriana.” Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies 29, no. 3-4 (1999): 54-65.

Torregrossa, Michael A. “The Way of the Wizard: Reflections of Merlin on Film.” In The Medieval Hero on Screen: Representations from Beowulf to Buffy. Edited by Martha W. Driver and Sid Ray, 167-191. Jefferson: McFarland, 2004.

Torregrossa focuses on uses of the Merlin character on screen. Starting with his earliest appearances, Torregrossa establishes how the “elderly fellow, big gray beard, pointed hat” incarnation became the popular image. The author then turns to the various roles of Merlin as guide and mentor, also exploring the appropriations of Merlin in works such as Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings.

Torregrossa, Michael A. “Will the ‘Reel’ Mordred Please Stand Up? Strategies for Representing Mordred in American and British Arthurian Film.” In Cinema Arthuriana: Twenty Essays. Revised ed. Edited by Kevin J. Harty, 199-210. Jefferson: McFarland, 2002.

Umland, Rebecca A. and Samuel J. Umland. The Use of Arthurian Legend in Hollywood Film: From Connecticut Yankees to Fisher Kings. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1996.

The authors explore 18 Arthurian films, categorizing them as intertextual collages, melodramas, propaganda, epics, and postmodern quests with Arthurian subplots and themes.

Wilhelm, Arthur W. “Moviemaking and the Mythological Framework of Walker Percy’s Lancelot.” The Southern Literary Journal 27, no. 2 (1995): 62-73.

Williams, David J. “Sir Gawain in Films.” In A Companion to the Gawain-Poet. Edited by Derek Brewer and Jonathan Gibson, 385-392. Woodbridge: D. S. Brewer, 1997.

Although Gawain has only appeared in less than 1 dozen Arthurian films, Williams believes the films are “usefully representative of the range of cinema itself, from lavishly spectacular productions to the intimacies of the television screen, from routine products of the industry to the work of individual auteurs at the boundaries of film art.” Williams dedicates much of the article on portrayals of Gawain in big-budget films such as Knights of the Round Table (1953), Sword of Lancelot (1963), and Prince Valiant (1954). Lesser-known works “ransack” some of the original elements the Green Knight story, including Gawain and the Green Knight (1973) and Sword of the Valiant (1984). The made-for-television movie Gawain and the Green Knight (1991) is the one attempt at remaining faithful to the original medieval poem.

Womack, Caroline. “Merlin: Magician, Man and Manipulator in Camelot.” In Hero or Villain? Essays on Dark Protagonists of Television. Edited by Abigail G. Scheg and Tamara Giradi, 109-122. Jefferson: McFarland, 2017.

Wood, Gerald C. “The Life of Art in François Truffaut’s Day for Night.” Interpretations 11, no. 1 (1979): 67-74.

Wymer, Kathryn. “A Quest for the Black Knight: Casting People of Color in Arthurian Film and Television.” The Year’s Work in Medievalism 27 (2012).

Wymer explores the roles assigned to actors of color in Arthurian-related productions, revealing the associated commentary or lack thereof related to skin color shows an evolving perspective on people of color in medieval Europe.

Yang, Ming-Tsang. “From Camelot to Sandlot: Gothic Translation in A Kid in King Arthur’s Court.” Medieval and Early Modern English Studies 17, no. 1 (2009): 63-88.

Zarandona, Juan Miguel. “Daniel Mangrané and Carlos Serrano de Osma’s Spanish Parsifal (1951): a Strange Film?” Arthuriana 20, no. 4 (2010): 78-98.