After the extreme fictionalization of Artemisia in the blockbuster 300: Rise of an Empire (2014), I wondered how historians depicted her throughout history. What survives leaves massive gaps in the historiography, but what remains creates a narrative that remains true to Herodotus’s original depiction of Artemisia.

After Salamis, the fate of Artemisia remains lost to history. Based on conjecture, it is possible to conclude that her city remained loyal to the Persian Empire for some time, passing down an heirloom for several generations bearing the inscription of Xerxes “Great King.” ((Pierre Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire, trans. Peter T. Daniels. (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2002), 560.))

Herodotus’s account of Artemisia remained prominent in the minds of the Greeks. During Salamis, there was a bounty for capturing her alive “because the Athenians held it such a scandal that a woman should be making war on Athens” (Herod. 8.93). Writing 30 to 60 years after the battle, Herodotus likely had a romanticized version of events. However, there is no reason to question the Greek disdain for a woman leading in war, which is at the heart of the bounty story.

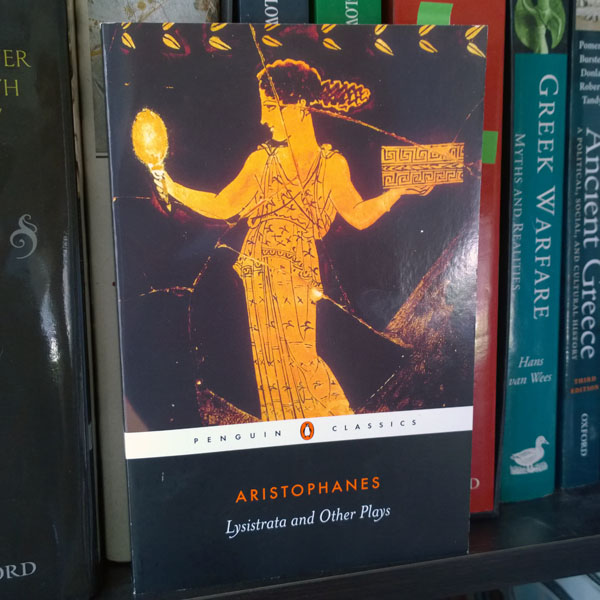

This disdain persisted and Artemisia appeared in Aristophanes’s comedy, Lysistrata (411 BC). In the play, women begin asserting their authority by withholding sex from the men in a bid to end the Peloponnesian War. One of the faceless male characters fears what may happen “if once we let these women get the semblance of a start.” The women may become “adept at every manly art.” With such skill, they would “turn their hands to building ships,” and “fight our fleet and ram us, just like Artemisia did” (Aristoph. Lys. 672-674). ((This translation comes from the Alan H. Sommerstein translation (New York: Penguin, 2002).))

Although brief, it demonstrates that Artemisia’s exploits at Salamis were still prominent in the minds of Athenians, nearly seventy years later. The notion of Artemisia ramming a ship is still prominent. However, the anecdote indicates that she rammed Greek ships, as opposed to an allied Persian ship while she served under Xerxes at Salamis, as Herodotus described. It is important to remember that Herodotus told a single story of Artemisia ramming a ship, but he never indicated that was the only one. It is very plausible that Artemisia was responsible for ramming other ships during the battles of Artemisium or at Salamis.

Nearly 600 years later, in the second-century AD, Pausanias recorded a pillar in Sparta that featured figures from the Greco-Persian Wars, including Artemisia, whose story he knew (Paus. 3.11.3). If this pillar existed, no one has found it. I looked all over ancient Sparta last September and came up short.

Further appearances of Artemisia in the ancient world serve only to confirm or enhance Herodotus’s account, never alter his version of events.

Plutarch (46-120 AD) barely mentioned her in a story of finding a dead Persian commander at Salamis (Them. 14.3). Similarly, Polyaenus (c. second-century) claimed she used Greek signal flags to trick her enemies, a plausible ploy (Strat. 8.53.1-5).

Justin (c. fourth-century) summed up the entire theme of Herodotus’s account in a single sentence, “Artemisia, queen of Halicarnassus, who had come to support Xerxes, fought with great spirit amongst the foremost generals; indeed, one could see in a man a woman’s timidity, and in a woman a man’s courage” (2.23-24). ((This translation comes from the J. C. Yardley translation (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1994).))

Likewise, Orosius (c. 375-418) described how Artemisia “plunged so fiercely among the leaders of the front ranks of the battle that it seemed as if their roles has been reversed, for a feminine caution was seen in the man and a masculine daring in the woman.” ((A History Against the Pagans, 2.10.3. This translation comes from the A. T. Fear. Liverpool translation (Liverpool University Press, 2010).))

Although none of these histories provide near as much detail as Herodotus, they did not alter his version of Artemisia. That sort of fictionalization would not occur until the late Medieval Period, which we will cover in future articles.