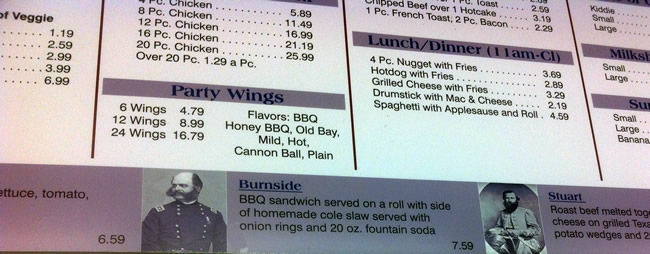

After the “Sunrise in Cornfield” program, Derek and I headed over to the Battleview Market for omelets and French toast. I was tempted to order the Burnside, but it was too early in the morning.

After the heavy attendance of the morning program, we expected the All Day Hike to be packed. We met behind the visitor center along with hundreds of other people.

Here is roughly the path of the hike during the first half of the day, which took us to the Cornfield, then the West Woods, and finally down to the Sunken Road.

Initially, we could not get a full count of people in attendance, but we were estimating at least 300. The rangers posed us for a photo and then we trekked north to the Cornfield.

The path we took required the group to form into a single line. This allowed the rangers to count us and provide an accurate total of attendees. This became a “teachable moment,” as the rangers called out for guesses from the crowd. Most folks were in the 400-600 range with a high estimate of 900 and a low estimate of 300. The final count was 585. Being tucked in the middle of the mass of humanity, it was difficult to gain an accurate count. My best guess was at least 400. This is something to consider when reading accounts from participants in battles.

In the West Woods, the rangers took the opportunity to line up people and describe maneuvers, as well as explain how a unit may react to a flank attack. The rangers described the “accidental ambush” by the Confederates, as they attacked the flank of a Union line in these woods. The result was 2800 casualties in a mere 20 minutes known as the West Woods Massacre.

We then headed back to the visitor center for a quick bio-break. Afterward, we headed for the Sunken Road. As we approached, the rangers told us to split up. They did not explain why, but they said, “Federals go that way. Confederates go that way.” I chose the latter.

We lined up in the sunken road and waited for a bit. The other group appeared over the hill facing us.

This was one of the better demonstrations of the Antietam terrain. People began to appear over the hill and suddenly there were hundreds upon us.

The rangers described the scene 150 years ago, as several thousand Confederates initially sat in this road and began to see flags, then bayonets, and eventually troops to the tune of 10,000 come down this hill.

The first part of the hike was roughly 3.5 hours. Toward the end, Derek and I met up with Craig Swain, a fellow Civil War blogger and the first person I would turn to with an artillery question. If you have not seen his blog, I highly recommend it. The man has served and contracted in multiple wars. His wealth of knowledge and passion for the Civil War is overwhelming and refreshing. We all caught lunch over in Boonsboro and made it to the Antietam National Cemetery in time for the second part of the hike.

This is roughly the path of the hike. It involved a lot more walking.

From the National Cemetery, we made a lengthy trek down to Antietam Creek and spent some time with the rangers discussing Burnside Bridge. The rangers addressed some obvious misconceptions people have on Burnside’s assault. By walking a good portion of the creek, it was easy for us to comprehend why Burnside did not skip the bridge entirely, as a large ridge ran along the west side of the creek. It would have been impossible to move thousands of men up it in a reasonable fashion.

The rangers finished the hike here to discuss the final assault by Burnside’s corps, as well as the Confederate counterattack that ended the battle. The group had dwindled some, but we were still at least 300 strong. It took roughly an hour to move from the National Cemetery down to the creek. It is important to keep this in mind when historians fault Burnside for taking a few hours to move 8,000 troops across the creek, line them up for battle, and then move forward across steep, rolling hills.

This was another experience I will never forget.