Anat Zanger identifies Alien 3’s Ellen Ripley as a cinematic Joan of Arc in disguise. After re-watching the film for umpteenth time, I’m not only convinced, but I would like to highlight and humbly augment Zanger’s analysis, as it might explain why I have loved this film for years while so many have derided it.

Zanger, professor of Film and Television at Tel Aviv University, includes the Ripley-Joan analysis in a larger thesis—the general structure of the Joan of Arc story in Western culture has been retold for over 100 years in cinema with a predefined set of norms that present different, yet “acceptable” versions of the story. Historians such as Robin Blaetz have made similar points, identifying common elements that when combined, reveal a Joan of Arc.

For Zanger, there are three major elements to the Joan of Arc story:

- Joan hears and heeds the commands of voices.

- Joan wears men’s clothing.

- Joan is tried.

While movies explicitly about Joan of Arc are easy to examine in this framework, Zanger argues that even if a film such as Alien 3 does not “declare” a “connection to Joan of Arc” through its title, the film still has “the three major elements” and then some. More succinctly, Alien 3 “revolves around a young woman struggling for her ‘truth’ against a society that wishes to control her sexuality.”

With this in mind, I’ll highlight the 9 elements Zanger finds in Alien 3 that come straight from the Joan of Arc story and whether they make it a true Joan of Arc film.

- Voices

- The Mission

- The obstacles on the way to achievement

- A change of dress

- Shaving the head (optional)

- Success

- Interrogation

- Betrayal

- Death by fire and recognition (limited) after death

To this list, I will add the following element that Alien 3 mimics from Joan of Arc films:

- A leader of men

First, the Basic Plots of Joan and Ripley

For those unfamiliar with the Joan of Arc story or the Alien 3 plot, here are some spoilers. In the 1420s, Joan of Arc claimed to hear voices of saints that instructed her to go to the Dauphin of France, lead his army to lift the English siege of Orléans, and then ensure the Dauphin was crowned king. She managed to do this, having several military successes (and failures), but was eventually captured, tried as a heretic, convicted, and burned at the stake.

Almost immediately, obvious parallels appear in Alien 3. Like Joan, Ripley finds herself in a male world, literally described as “Double Y Chromosome-Work Correctional Facility” on planet Fury 161. The announcement that a woman has crash-landed on the planet sends the religious, celibate inmates into protest.

As is often depicted in cinema, Joan’s initial presence among the French army is seen as unnecessary, a nuisance, just like Ripley. One of the inhabitants can be heard saying off camera, “What trouble can she become?” Another responds, “She’s already changed everything.”

Ripley learns that her crash-landing was due to an alien. She then toils to convince the inmates to kill the alien before an ominous corporation (“the company” in the film) arrives to capture the creature and weaponize it. The inmates fight and die alongside Ripley, eventually killing the creature just as the company arrives. While their initial prize is destroyed, they learn that Ripley is impregnated with a baby alien that is ready to burst forth from her chest. Realizing this, Ripley opts to throw herself into a furnace, burning her and the baby alien alive.

Now, onto Zagner’s elements.

Voices

Joan claimed to receive guidance from saints Michael, Margaret, and Catherine, which she often referred simply to as “my voices.” These voices gave Joan seemingly prophetic abilities that amazed some and scared others. Zagner argues:

Like Joan, Ripley’s “encounters of the third kind” (with an angel in one case, an alien in the other) provide her with special knowledge. As a result “voices” from another world echo in her mind. Interestingly, society reacts to the voice in both places in a similar manner.

Zanger’s angle is more of a nuanced approach to the voices trope and frankly, the least convincing.

More to the point was Ripley accessing her ship’s flight recorder to determine if there was an alien on board before she crash-landed. Lacking any computer with audio capabilities, her solution is jiggering Bishop, the remains of a defunct android from the previous film. In a gruesome scene that depicts the remains of Bishop leaking fluids from every orifice, the android describes what she already believed to be true—there was an alien on her ship and that’s why it crashed.

Bishop switches from his default male voice to a computerized female voice from the ship, recounting the events. Ripley’s saints are gendered computer voices.

Afterward, Bishop asks Ripley to disconnect him, because he’ll “never be top of the line again.” She pulls the plug in an act of mercy, ensuring that no one else will hear the same information (voices) she heard.

The Mission

Zanger mentions “the mission,” which was a key element for Joan. From the saints, Joan learned that she was to lift the siege of Orléans and see the Dauphin crowned king of France. For Ripley, she must ensure the alien is destroyed and “the company” does not get its hands on the alien for its bioweapons program. She pushes this mission throughout most of the film, having to convince men over and over of what she knows to be the correct course of action (from her voices and experience).

The obstacles on the way to achievement

Zanger mentions Ripley’s “obstacles on the way to achievement,” but doesn’t list them. The list is jarring when you consider that Ripley is nearly raped, lacks traditional weapons, and fails in one epic battle against the alien that results in 10 casualties, nearly half of the inmates. The latter leads to an obvious loss of faith in her leadership from the men, a similar problem Joan faced with her obstacles.

When Ripley confirms that she is “impregnated” with an alien parasite, she fails in one suicide attack against the adult alien and she fails to convince others to kill her. If we look at these as obstacles in her ultimate mission—kill the alien and obstruct the interests of the company—then they parallel Joan’s obstacles to lift the siege of Orléans and crown the Dauphin.

A change of dress

Joan of Arc’s male attire is key trope to her story, even though some cinematic and artistic depictions add some “feminine” aspect, such as a skirt to go with her plated armor. In the trial, her male clothing was a key focus, as she continually refused to put on women’s clothes. Often in films, there is a moment where Joan dons male clothing for the first time and everyone takes notice.

Similarly, there is a distinct moment when Ripley discards her old attire for what was available on a Double Y Chromosome planet—clothing fit for male inmates.

She wears it with confidence and struts in front of the glaring men.

Shaving the head (optional)

Zanger points out that others already made the connection with Maria Falconetti’s shaved head in The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928). We can always find some reference or listicle mentioning the film when any female actress shaves her head for a role. Zanger says shaving is an “optional” element, likely because not all cinematic Joans follow this trope exactly. Many just enjoy a trim, which may be short but still socially acceptable by the day’s standards.

Yet, there is more here. Coupled with the change in dress, Robin Blaetz might describe this as the “rebirth” moment in the Joan of Arc story. Ripley is shown suddenly bald in the shower before she struts out in front of the men in their attire. Whatever she was when she landed on the planet, she has emerged as something entirely different.

Success

Zanger lists “success” as one of the similarities between Ripley and Joan, but does not include examples. Ripley convinces the survivors to take one more shot at killing the alien before the company arrives. This is difficult of course, as she needs to convince them that they will either die by the alien, or the company will kill them anyway. Although most of them die in the process, they do successfully kill the alien.

Interrogation

One of the most convincing angles from Zanger is the interrogation that happens earlier in the film.

The conversation takes place in the office of the commander, which has a barred window. Ripley, in men’s clothes, her head shaven (like Joan’s in many prison scenes), confronts the commander and one of his assistants who give no credence to her opinions.

The commander is unconvinced and condescending the whole time.

In addition:

Like Joan before her, Ripley tries to convince the commander to prepare for an offensive, but the commander, like Joan’s interrogators when her answers do not suit their expectations, decides to imprison her (in the installation’s infirmary).

Betrayal

Toward the end of the film, the only person alive with any real authority is the commander’s assistant. Ripley fails to convince him to help in a final attempt to kill the alien. Worse, the assistant notifies the company that Ripley is also carrying an alien parasite. When the company arrives, the assistant leads them right to Ripley.

Similarly, Joan is often portrayed as betrayed outside the gates of Compiègne where she was captured. There is often one or two lackeys giving intelligence to soldiers on where and how they can capture Joan.

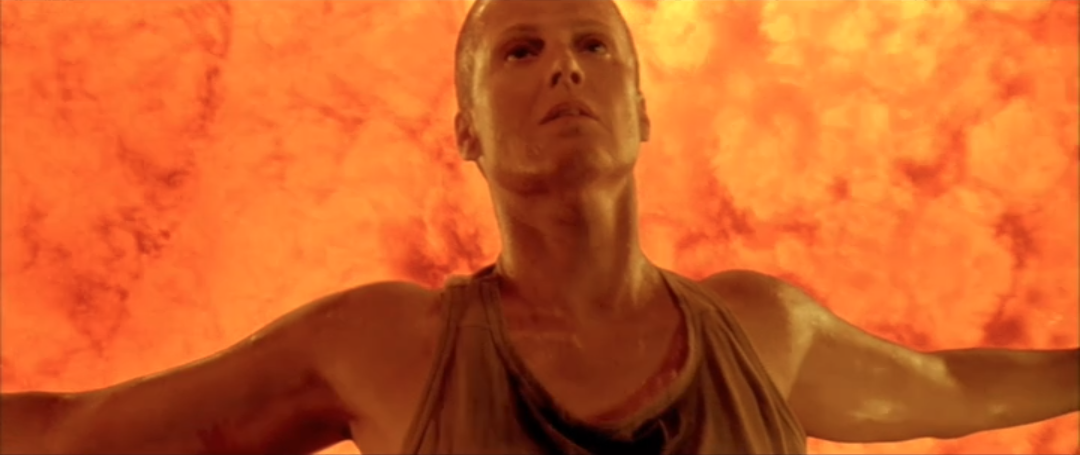

Death by fire and recognition (limited) after death

Zanger mentions Ripley’s death by fire briefly, but unfortunately does not expand on it, possibly because it seems so obvious (at first!). After leading the company men to Ripley, the betraying assistant realizes that she was right about their intentions the whole time. They want to capture, not kill the murderous alien. He picks up a pipe and hits one of the company men in the back of the head, getting himself shot in the process.

This scene is reminiscent of the oft depicted priest who held up a cross to Joan of Arc as she was burned–too little, too late.

More to the point is Ripley plunging to her fiery suicide.

That covers Zanger’s 9 elements and now we’ll look at one extra element to add to the list.

A Leader of Men

Although Zanger doesn’t list Ripley as “a leader of men” explicitly, Zanger brings up the moment of revelation after Ripley witnesses the alien kill someone.

“It’s here. It trapped Clemens in the infirmary!” To which the commander responds: “Take this madwoman to the infirmary.” Before he has finished the sentence the alien surprises him, grabs him from behind, raises him up and does away with him. There is a parallel here with the soldier in the battlefield who tries to undermine Joan’s authority and dies on the spot. This is justice from heaven, and is therefore unassailable vindication.

Zanger refers to Victor Fleming’s Joan of Arc (1948) where a similar scene occurs. The medieval version documented from an eyewitness was a little different. Joan of Arc warned a commander to move from a spot before a cannon hit him. He moved and was amazed when another soldier took up the same position and was hit by the cannon. The story is often presented as a miracle.

With the commander of the inmates dead and no one willing to lead the survivors, they turn to Ripley. Some are reluctant, but Dillon, the dominant personality among the inmates, becomes Ripley’s equivalent of a La Hire or the Duke of Alençon. These are two men that may have expressed doubts of fighting alongside of a teenage girl, but they ultimately worked with Joan. After Joan’s death, these men went on record, singing her praises as a leader of men.

Science Fiction Joan of Arc

When I first started reading Anat Zanger’s chapter about Alien 3’s Ripley as a Joan of Arc, I was reminded of Paul B. Sturtevant’s warning that sometimes our “quest to explore any and all medieval resonances risks generalising ‘medieval film’ (or medievalism) too far” and could lead to “labeling film tropes as specific to medieval films (when they are not).”

There are of course some major differences between Joan and Ripley. Ripley claims she has little faith, she isn’t celibate, and she has no problem cursing—three complete opposites of Joan.

Yet, even if the filmmakers did not set out to recreate the Joan of Arc story, they were obviously influenced by the ubiquity of the story’s elements that have been retold explicitly through roughly 30 films by 1992, as well as other movies that borrow heavily from the Joan of Arc story.

So yes, Ripley doesn’t really believe in god, sleeps around, and curses like a sailor. She’s also not the only cinematic woman to find herself alone among men, get a haircut, or even dress like a man (e.g., G.I. Jane). But when Ripley has sole access to voices that send her on a critical mission, when she must lead reluctant men into battle, and when she dies by fire at the end of the film, we start running out of methods to explain away the similarities between Alien 3 and the Joan of Arc story.

This leads us to Zanger’s larger point about interpretations of Joan of Arc:

The fact that Western culture returns again and again to the same story testifies to the fact that the conflict between the social order and Joan’s challenge to it has not yet been resolved. Thus, despite Joan’s official canonization (in 1920), night after night, at movie houses and theaters all over the world, she is still being burned alive.

Alien 3 is part of Joan’s legacy that still runs strong nearly 600 years after her execution.