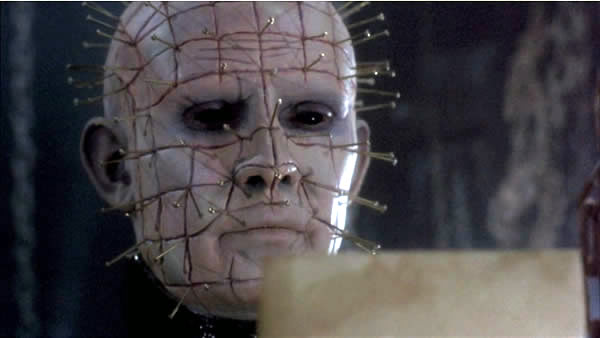

The Hellraiser franchise features some of the most unforgettable imagery, even if you haven’t seen a single film. Pinhead is a pop-culture icon who sits comfortably alongside Freddy Kruger and Jason. My parents wisely kept me away from these movies as a child, but in my rebellious 30’s, I have watched them with an initial tongue-in-cheek delight.

What became apparent was the eagerness of the filmmakers to incorporate war as a parallel to the depicted horror, especially in the second and third installments of the franchise. While some of this was blatant with direct ties to World War I and Vietnam, there are unintended undertones that fit perfectly with the theme that war is hell.

The basic premise of these films is that there is a puzzle box promising ultimate pleasure and pain. Solving it unleashes Pinhead and his demonic friends who literally tear people apart with chains. With 1980s special effects of stop motion and claymation, this is particularly horrific even today.

The first Hellraiser (1987) kept Pinhead shrouded in mystery. With the follow-up of Hellbound: Hellraiser II (1988), we learned that he was previously a man, Captain Elliot Spencer. A single black-and-white photo helps Pinhead remember his former self.

With the release of Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth (1992), the backstory reveals that Spencer fought in World War I. After the war, he sought relief from the experience, which led him to the puzzle box that transformed him into Pinhead. As the Spencer character puts it

The war pulled poetry out of some of us. Others it affected differently. I was like many survivors, a lost soul with nothing left in which to believe but gratification. We’d seen God fail us; so many dead. For us, he too fell at Flanders. The war destroyed my generation. Those that didn’t die drank themselves to death. I went further. I was an explorer of forbidden pleasures. Opening the box was my final act of exploration—of discovery.

This movie toils to emphasize its “hell on earth” title with dream sequences of Vietnam and the trenches of World War I.

One Hellraiser expert–if it’s not a title, it should be–has already analyzed how the film sought to link “past and present, unreality and reality.” ((Paul Kane, The Hellraiser Films and their Legacy (Jefferson: McFarland, 2006), 115.)) Vietnam and World War I brought about the same death and psychological destruction to the survivors. When Pinhead arrives on earth and slaughters everyone in a nightclub, the aftermath is like that of a battlefield. He narrates the scene for one onlooker:

Oh, it’s unbearable isn’t it? The suffering of strangers, the agony of friends. There is a secret song at the center of the world, Joey, and it sounds like razors through flesh.

World War I, Vietnam, and a 1990s nightclub are “each, in equal respects, a Hell on Earth.” ((Paul Kane, The Hellraiser Films and their Legacy, 116.)) Or as Spencer’s character puts, “A dream of one war is a dream of all wars.”

The filmmakers allude to this point with a scene of a woman sitting around reading a book about battles of the 20th-century.

As unworldly as Pinhead seems in these films, director Anthony Hickox emphasizes

There is a strong analogy between warfare and how Pinhead learns to kill people. Because Pinhead was a human being in war, I am really saying that he has learned most of his methods of killing from human beings, not from any Devil. ((Paul Kane, The Hellraiser Films and their Legacy, 116.))

The Brits involved with the film, descendants of those who fought and died in World War I, wanted to make the connection obvious. Doug Bradley, the British actor who plays Pinhead, tells us in the audio commentary to Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth

Just before we came out to film it, there was a documentary on BBC about survivors of the Somme and one of the guys said this extraordinary thing I just grabbed hold of, talking about all his comrades who had died on the first day of the Battle of the Somme—something like 60,000 British troops were killed or injured in the first 24 hours. He felt as though he had cheated, that he was in the wrong place, that he shouldn’t have lived, that he should be dead and he should have been buried along with his comrades in France. And I thought that’s exactly Elliot’s thing. That’s exactly what leads him from there to this.

Eagerness and regret for war, for the puzzle box

With these obvious connections to war, moving into this theme has opened plenty of undertones for the puzzle box itself. It is fitting that Pinhead was a captain in World War I in his former life. The eagerness to find and open the Hellraiser puzzle box followed by immediate regret mimics the naive eagerness and eventual regret for war in 1914. British diplomats described cheering in Berlin and Vienna at the prospect of war. ((Martin Gilbert, The First World War: A Complete History (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1994), 24, 26.))

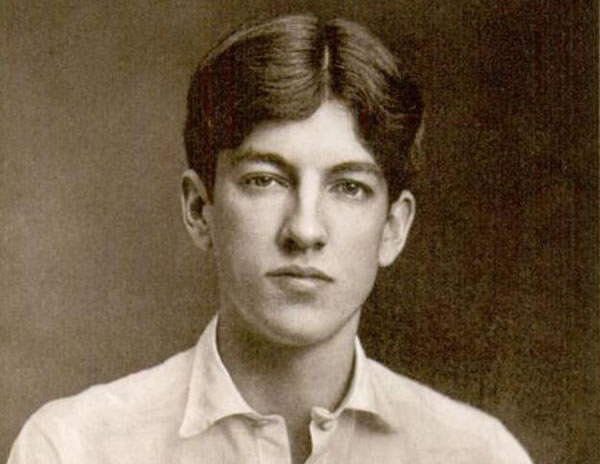

On an individual level, the American poet Alan Seeger enthusiastically joined the war well before America officially entered the fray, enlisting in the French Foreign Legion less than a month after the war started. Seeger was not only fatalistic, but eager to seek out danger and even death. From the trenches, he wrote in his diary in 1915

What have they got up their sleeves for us? Where shall we find the strongest resistance? I am very confident and sanguine about the result and expect to march right up to the Aisne, borne on in an irresistible élan. I have been waiting for this moment for more than a year. It will be the greatest moment in my life. I shall take good care of it. ((Entry on September 24, 1915 in Letters and Diary of Alan Seeger (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1917), 163.))

This excitement comes through in his famous poem “I Have a Rendezvous with Death” in which he proclaimed “And I to my pledged word am true / I shall not fail that rendezvous.” Similarly, in his “Champagne, 1914-15” poem, he describes marching “to the heroic martyrdom.”

Seeger’s regret would not come until the Battle of the Somme where he and others fell charging German machine guns. Lying out in no man’s land, Seeger cried out for water and for his mother before he died there. ((Martin Gilbert, The First World War: A Complete History, 263.))

The Hellraiser puzzle box becomes a perfect allegory for the youthful enthusiasm for war that even the most ardent supporters eventually regret. The box promises the ultimate in pleasure and pain. Those opening it tend to seek the pleasure just as Seeger wanted the glory. Instead, the war, like the box, only delivered pain to Seeger. For all his gusto, Seeger had no “heroic martyrdom,” only a sad, pointless death.

Continuing with the parallels, Captain Elliot Spencer as Pinhead is covered in pins with scars all over his body. These are the prominent features that everyone remembers. In Spencer’s monologue about the war, he tells us “Those that didn’t die drank themselves to death. I went further.” This hints at the PTSD that soldiers suffered since the beginning of written history—Ajax famously became violent and eventually killed himself after the Trojan War. Yet, something missing in Spencer’s monologue are the physical scars veterans brought home from the war. Like Pinhead, they wear them daily. Those who go to war come back with physical and psychological changes just as those who opened the Hellraiser box.

Can horror films discourage us from war?

The obvious and not-so-obvious military history of Hellraiser is fascinating if you can stomach the movies. The first two are classics in the horror genre. The third one is an acquired taste. Like many things in Hollywood, there should have been an earlier end to the series and the next 6 installments range from barely tolerable to terrible.

I’ll be honest that watching them was youthful rebellion. They are full of grotesque violence that is difficult to watch. But what struck me is that there was something familiar to the scenes of soldiers dying in Vietnam and the First World War in Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth. I’d seen these countless times in other productions and they didn’t faze me. Even the depictions of soldiers dying in slow motion, limbs flying, and then bodies mutilated across the battlefield had little effect, because I’ve seen all this before. Perhaps in viewing war scenes, we often feel that with better technology, training, and leadership, we could survive the battle. At worst, we might gain Alan Seeger’s “heroic martyrdom.” That gives us some sort of hope. Having stood in the trenches of the Somme and Verdun, I know this is fallacy, but you can’t transport everyone to a battlefield for a history lesson.

On the other hand, seeing someone’s skin ripped off with chains still makes me cringe like no Hollywood war scene can. It’s not just the hyper violence, it’s the feeling that there’s no escape from it. As such, the horror scenes of Hellraiser pierce the desensitized veneer of today’s audience that has seen countless war movies.

If you’ve made it this far, you’ve no doubt thought how silly it is that I sat through these films (multiple times), but in the same breath might accept the violence of war movies as necessary to emphasize “real war.” My parents took me to see ultraviolent Glory (1989) the year after they wouldn’t let me see Hellbound: Hellraiser II. The Civil War classic shows men getting their heads blown off and an entire regiment destroyed in an assault on a fort. Yet, even with these depictions readily available, there are war hawks eager to open the puzzle box.

Perhaps, the heightened level of Satanic violence in films such as Hellraiser can have the effect war movies are losing, giving people a healthy dose of fear of violence and dying. Perhaps, it can prevent future Alan Seegers from emerging in our time.