Frank Miller’s second issue of Xerxes: The Fall of the House of Darius and the Rise of Alexander hit shelves this week and here is the historical hottake (see review of Xerxes #1).

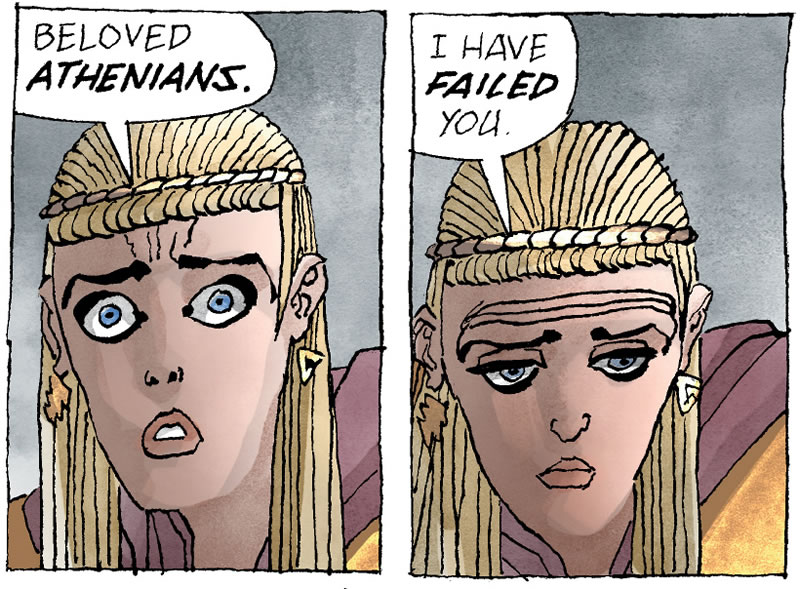

The story picks up after the Greek victory at Marathon (490 BC), following the famous runner to deliver the news to a defenseless Athens. The effeminate-looking Miltiades leads a tired Greek army back to Athens to confront the Persian fleet that sailed from Marathon. Upon his arrival, Miltiades loses heart and gives up leadership entirely.

Although Themistocles does not refer to Miltiades as a “fop” in this issue, the disdain is still there. Miller depicts Themistocles taking up the banner of leadership, implementing a plan to stand at the shores with armored men, women, and slaves while Miltiades sits dumbstruck.

This is an extraordinary retelling the story of outside Athens, as Herodotus gives us none of it. He simply states after the Greek army marched back to Athens,

The Barbarian fleet anchored off Phalerum (which in those days was still the main port of Athens), until at length, after its ships had been moored there for a while, it sailed away back to Asia (6.116).

The notion of Miltiades being some ineffectual military leader is a new one. Herodotus tells us he is the reason the Greeks decided to fight at Marathon in the first place, having to convince a council of 9 other generals (6.109-110). The modern-day analysis of Miltiades is legion, but they all tend to proclaim something along the lines of

His brilliant strategy and his persistence in carrying it through, despite opposition, brought about victory against extraordinary odds. ((Robert J. Lenardon, The Saga of Themistocles (London: Thames and Hudson, 1978), 40.))

The Greek geographer Pausanias (c. 175 AD) tells us there was a statue of Miltiades at Delphi (10.10.1). It’s remarkable that the Greek general still had a statue in such a prominent place nearly 700 years after his death. Although the ancient statue is lost to us now, there is a modern bronze statue on the plain of Marathon today.

Conversely, Herodotus makes no mention of Themistocles even fighting at Marathon. ((Lenardon, The Saga of Themistocles, 43.)) This isn’t to say that he wasn’t present at all, as what we know of his career would have put him smack in the middle of the events at Marathon. Only Plutarch, writing more than 400 years later, even mentions Themistocles fighting alongside the troops in the center line at Marathon, but never taking up a position of leadership (Life of Aristides 5.3).

There are likely multiple reasons for Miller’s effort to downplay Miltiades while overplaying Themistocles. First, Miller needs to create a hero equal to that of Leonidas, as portrayed in 300. Second, by portraying Miltadies and Themistocles as hyper-feminine and -masculine, respectively, Miller is likely making a play on the famous statement of Xerxes: “My men have become women, and my women men” (8.88). Finally, Miller is pushing a rags-to-riches story with Themistocles by portraying him as rising from the ranks and employing the use of women and slaves to put on a show of force, the latter of which is never mentioned in the ancient sources.

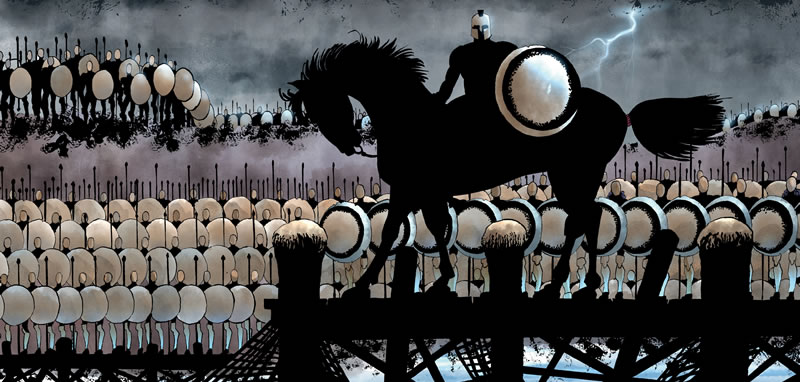

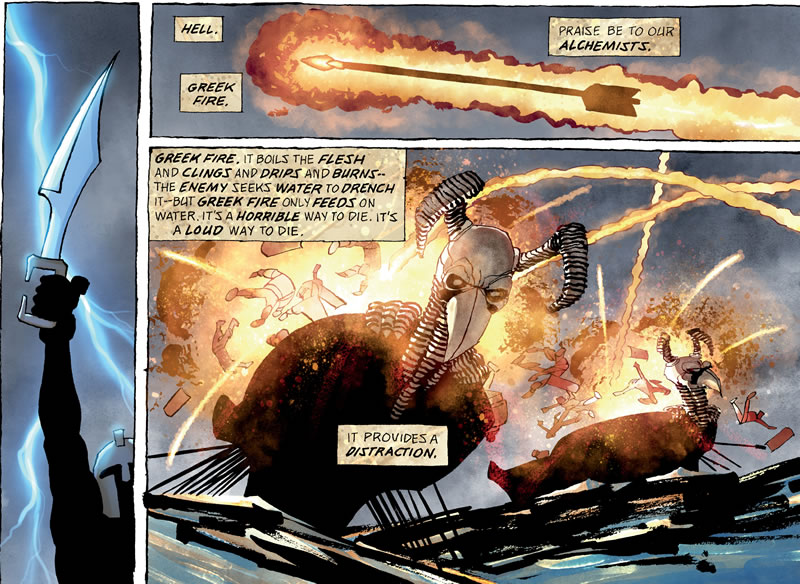

Back to the Xerxes comic book, the Greeks employ Greek fire to burn some of the Persian ships while throwing a javelin from afar to mortally wound Persian King Darius in front of his long-haired son, Xerxes. Darius makes Xerxes swear to give up any further conquest of Greece and to get him home before he dies.

Miller’s version of Greek fire appears to be fiery arrows that can explode on impact. Greek fire is a modern term used to describe a weapon first employed on Byzantine ships that would pump a liquid substance through a hose and ignite on its way to enemy ships. There are numerous theories about what was in the substance exactly, but we do know it was liquid, sticky, and flammable. The earliest evidence of Greek Fire was in the 7th-century AD, nearly 1,200 years after the Battle of Marathon. ((Bernard S. Bachrach and David S. Bachrach, Warfare in Medieval Europe, c. 400-c. 1453 (London: Routledge, 2017), 250-251.))

The presence and death of Darius at or near the time of Marathon is something that both 300: Rise of an Empire and now the Xerxes comic have pushed. In the former, Darius is wounded at Marathon by Themistocles. In the comic book, he is wounded by the playwright Aeschylus outside Athens. Both use similar methods to tossing a projectile at the king from afar, leaving Xerxes unable to retaliate.

However, Herodotus never put Darius anywhere near Marathon or Athens, as he was instead fighting at Sardis in what is modern-day Turkey. There was no indication that he wanted to cease hostilities in Greece and he instead began amassing an even larger army after Marathon. As Herodotus tells us,

Accordingly, he wasted no time in sending messengers to city after city, with instructions to raise troops: requisitions that in every case were more onerous than they had been the last time, and required the supply not only of ships, but of horses, food and transport vessels as well. These demands, which meant the enrollment and readying of the elite of Asia for the campaign against Greece, served to put the continent in a state of upheaval for three whole years (7.1.2).

Does this sound like a king ready to throw in the towel against Greece? Before he could invade again, he died sometime in late-486 BC, more than 4 years after his death in the comic book. ((The last inscriptions of Darius date to December 486 BC. Amélie Kuhrt, The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period (London: Routledge, 2007), 236.))

The wounding of Darius in front of Xerxes serves to gives the prince-turned-king something to avenge. Darius proclaiming his mistake of ever invading and pushing Xerxes to do the same is somewhat reminiscent of Aeschylus’s play The Persians. In the play, the ghost of Darius rebukes Xerxes for his hubris on how he conducted his later Greek expedition in 480 BC, predicting even more defeat for the Persians.

The comic book ends with some sort of desert ritual, as Xerxes approaches what I can only describe as a living mummy. The desert journey is again reminiscent of 300: Rise of an Empire, not the historical record.

It is unclear where the next issue will go, as Miller has already produced 300 that tells the story of Thermopylae. Will he skip over these events and focus on Artemisium, Salamis, and eventually Plataea? Will Artemisia make an appearance? Or will he venture from Greece and instead tell of Xerxes crushing revolts in places like Egypt. We’ll find out next month.