Some of my most cherished books are my West Point atlases. These thick, spiral-bound works offer loads of maps to supplement the hundreds of war books that fill my shelves. My latest purchase is Summaries of Selected Military Campaigns, published in 1961. Unlike the other West Point atlases, this book has some text around each map describing movements and results. The majority of the book focuses on the major battles in between and including the Napoleonic Wars and the Korean War. West Point was not the only beneficiary of the 175-page book, as it acted as a textbook in a military history course at the United States Air Force Academy.

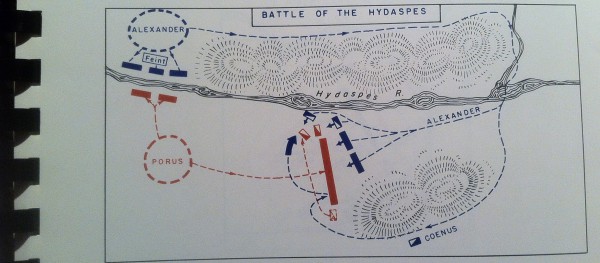

Here is a sample of one of the maps:

The Great Captains before Napoleon

The most intriguing part is the small section at the beginning entitled “Great Captains before Napoleon.” It is only seven pages long, but it provides a clue as to which military commanders prior to Napoleon received attention from at least two schools of war more than 50 years ago.

Here is the list of those that made the cut.

- The authors believed Miltiades at Marathon (490 BC) and Epaminondas at Leuctra (371 BC) are two notable examples prior to Alexander the Great featuring maneuver. These battles went against the norm of armies generally facing “each other in line and fought until one or the other was defeated.” ((Vincent J. Esposito, Summaries of Selected Military Campaigns (West Point: United States Military Academy, 1961), 3.))

- With the arrival of Alexander, the authors included the battles at Issus (333 BC), Gaugamela (331 BC), and Hydaspes (326 BC).

- Then with Hannibal, there are the battles at Trebia (218 BC), Lake Trasimene (217 BC), and Cannae (216 BC) where the Carthaginian crushed his opponents in each battle.

- Caesar received a nod for his victory over Pompey at Pharsalus (48 BC).

- The authors then skipped 1800 years of history to Frederick the Great’s battles at Prague (1757), Rossbach (1757), Leuthen (1757), and Torgau (1760).

The selections are typical. Everyone has heard of Caesar and Alexander. Hannibal and Frederick are less prominent in popular memory today, but many have at least heard of them. With the disappearance of Greek in Western schools, Miltiades and Epaminondas are probably the least recognizable for most people. Regardless, most books covering the period before Napoleon would include most if not all of these selections in compiling a list of important commanders and battles.

Who West Point Snubbed

The following exercise is a look at who West Point snubbed in this list. Given that the past 50 years has drastically changed the landscape on accessible information concerning ancient and medieval battles, I will limit any candidates to those mentioned in works by Hans Delbrück (1848-1929), Charles Oman (1860-1946), and B. H. Liddell-Hart (1895-1970), which had all seen publication by 1927. Meaning, these battles were easily accessible to historians in 1961.

Chief among the snubs in the ancient world would be Scipio’s victory over Hannibal at Zama (202 BC). It was an overwhelming victory, featuring maneuver, against the man with three battles in the West Point atlas. Delbrück believed Scipio deserved “to be placed, certainly not above, but nevertheless, with complete justification, beside Hannibal.” ((Hans Delbrück, Warfare in Antiquity, translated by Walter J. Renfroe, Jr., (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1990), 385.)) B. H. Liddell-Hart went further to place Scipio above Napoleon in his analysis, stating that at Zama, “Scipio not only proved capable of countering each of Hannibal’s points, but turned the latter’s own weapon back upon himself to his mortal injury.” ((B. H. Liddell-Hart, Scipio Africanus: Greater than Napoleon (London: Greenhill Books, 1992), 190.))

What is most damning about the omissions in the West Point book is the complete lack of medieval battles and there are numerous worthy of examination. It is as though 1800 years’ worth of warfare never occurred. Easily accessible were the exploits of Byzantine commander Belisarius (c. 500-565) who led armies that helped extend the empire to its greatest size, winning battles in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. At the Dara (530), he used his combined-arms to withstand the assaults of a larger Persian force, eventually gaining, retaining, and exploiting the initiative. Charles Oman referred to him as a “great general,” providing extensive details of his battles. ((Charles Oman, A History of the Art of War in the Middle Ages, vol. 1 (London: Greenhill Books, 1991), 31.)) More importantly, Oman was impressed with his ability to win these battles while always outnumbered. ((Ibid., 30.))

Then there is Genghis Khan (r. 1206-1227), a man whose conquests overshadow all other conquerors in history. There was also his commander, Subotai (c. 1176-1248), who attack Europe and won victories over the Teutonic Knights, Germans, Russians, Poles, and Hungarians. Both commanders won battles that featured maneuver, surprise, and several other important tenants of military doctrine. B. H. Liddell-Hart believed that only Napoleon matched “the strategic ability of these two leaders.” ((B. H. Liddell-Hart, Great Captains Unveiled (New York: Da Capo Press, 1996), 3.))

As we move closer on the timeline to today, the sources becomes more detailed and reliable, giving us commanders like Swedish King Adolphus Gustavus (r. 1611-1632) and the Duke of Marlborough (1650-1722). Yet, this has barely skimmed the surface of 1800 years of warfare not even hinted at in this atlas.

Who else would you include?

Bibliography

These are all easily-accessible modern editions of the books mentioned above.

Delbrück, Hans. Warfare in Antiquity. Translated by Walter J. Renfroe, Jr. History of the Art of War 1. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1990.

Esposito, Vincent J. Summaries of Selected Military Campaigns. West Point: United States Military Academy, 1961.

Liddell-Hart, B. H. Great Captains Unveiled. New York: Da Capo Press, 1996.

______. Scipio Africanus: Greater Than Napoleon. London: Greenhill Books, 1992.

Oman, Charles. A History of the Art of War in the Middle Ages. vol. 1. London: Greenhill Books, 1991.