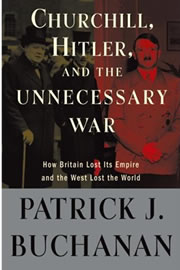

Editor's Note: This is the second installment of a five part series that takes a detailed look at Patrick J. Buchanan's Churchill, Hitler, and the "Unnecessary War" released in May of 2008. Further analysis of Buchanan's book can be found here.

Patrick J. Buchanan's goal of demystifying Winston Churchill is no easy task. The period of the 1930's was a time in which few, save for people like Churchill, saw the dangers of Adolf Hitler and Nazism. As early as 1930, Churchill told Prince Bismark of Germany that he "was convinced that Hitler or his followers would seize the first available opportunity to resort to armed force." Buchanan's method for dealing with warnings that were so obviously correct is simply to omit them. Instead, Buchanan focuses on the various crises that occurred leading up to World War II and in each instance portrays Churchill as weak, incompetent, or wrong. This approach involves omitting events, hacking quotes, and cherry-picking historians who agree.

Patrick J. Buchanan's goal of demystifying Winston Churchill is no easy task. The period of the 1930's was a time in which few, save for people like Churchill, saw the dangers of Adolf Hitler and Nazism. As early as 1930, Churchill told Prince Bismark of Germany that he "was convinced that Hitler or his followers would seize the first available opportunity to resort to armed force." Buchanan's method for dealing with warnings that were so obviously correct is simply to omit them. Instead, Buchanan focuses on the various crises that occurred leading up to World War II and in each instance portrays Churchill as weak, incompetent, or wrong. This approach involves omitting events, hacking quotes, and cherry-picking historians who agree.

Buchanan paints Churchill as weak on the Rhineland

When Buchanan describes Hitler's reoccupation of the Rhineland in March, 1936, he quotes Roy Jenkins to portray Churchill as "strangely unconcerned" with a delayed reaction toward the crisis. Here, Buchanan cherry-picks a historian who will best paint Churchill in a negative light. This is done purposefully since several other books that Buchanan quotes from extensively provide a different analysis. For example, Martin Gilbert, who is quoted throughout Buchanan's book, cleared up the issue by explaining that Churchill was opting not to publicly criticize the British government's inaction, because it was rumored he would soon be asked to join the Prime Minister's cabinet. Churchill had been nothing more than a Member of Parliament for several years and believed he could do more good in the cabinet than out of it.

Buchanan also left out that William Manchester, who is quoted in the same chapter, detailed Churchill's efforts to ensure that French diplomats seeking to do something about Hitler's reoccupation were linked up with prominent British politicians. Buchanan also ignores Churchill's own explanation in The Gathering Storm, again quoted in this chapter, which explained that Churchill's public outcry in the House of Commons was "delayed", because the topic was not officially debated until 19 days after the crisis. Buchanan has all these books available to him, yet he chooses Roy Jenkins to describe Churchill as "strangely unconcerned." This is but one example of Buchanan cherry-picking historical analysis that he does throughout the book.

Where was Churchill after the Annexation of Austria?

After Buchanan describes Hitler's annexation of Austria in March, 1938, he finishes it by asking "where was Churchill?" Buchanan simplifies Churchill's efforts by saying he "called for a warning to be sent to Hitler that if he invaded any other country, Britain would intervene to stop him." Buchanan cherry-picks from Burying Caesar by Graham Stewart to come to this conclusion, but why? Churchill's The Gathering Storm, which Buchanan quotes often, has much of the text from his speech that day. If Buchanan gave anymore details of Churchill's speech, the reader might begin to see Churchill in a positive light. In the speech, he pointed out that Czechoslovakia was Hitler's next target and stated:

How many friends will be alienated, how many potential allies shall we see go one by one down the grisly bluff? How many times will bluff succeed until behind bluff ever-gathering forces have accumulated reality? . . . Where are we going to be two years hence, for instance, when the German Army will certainly be much larger than the French Army, and when all the small nations will have fled from Geneva to pay homage to the ever-waxing power of the Nazi system, and to make the best terms that they can for themselves?

Churchill correctly assessed Hitler's next target and concluded that smaller countries would pay "homage" to the Nazis (e.g. Hungary, Romania). Yet, Buchanan dismisses the entire speech with "Churchill called for a warning."

Buchanan paints Churchill as a warmonger after Munich

After Austria, Buchanan jumps right to the Munich Agreement signed on September 30, 1938 which partitioned portions of Czechoslovakia to Germany. He gives a high-level overview of Neville Chamberlain visiting Hitler and coming home to excited crowds with the promise of peace. Buchanan must work hard to diminish Churchill who saw the agreement as a defeat and stated that Germany would eventually consume the rest of Czechoslovakia. Buchanan quotes the very end of Churchill's speech in the House of Commons on October 5 in which he gave a poetic warning concerning the recent events.

This is only the beginning of the reckoning. This is only the first sip, the first foretaste of a bitter cup which will be proffered to us year by year unless, by a supreme recovery of moral health and martial vigor, we rise again and take our stand for freedom as in the olden times.

Buchanan provides this quote as almost a concession to say "Yes, Churchill correctly predicted that Hitler would not stop there." But by quoting only this portion of the speech, Churchill's warning seems little more than dramatic and unspecific. Earlier in the speech, Churchill called out the next move by Hitler in exact terms.

I venture to think that in future the Czechoslovak State cannot be maintained as an independent entity. You will find that in a period of time which may be measured by years, but may be measured only by months, Czechoslovakia will be engulfed in the Nazi regime.

Indeed, the rest of Czechoslovakia was "engulfed in the Nazi regime" little more than five months after Churchill made that statement. But who does Buchanan give the credit for predicting Czechoslovakia's downfall? Hitler. When describing Czechoslovakia's crumbling state of affairs between the Munich Agreement and March, 1939, Buchanan points out that "Hitler had warned Chamberlain" that the remaining Czech country would "collapse and fall apart." He goes onto say that just "as Hitler had predicted, planned, and promoted, the disintegration of Czechoslovakia began as soon as Munich had been implemented." How much credit should Hitler get for predicting an event that he planned to cause? Apparently more than Churchill according to Buchanan.

To prevent the reader from gaining any sort of admiration for Churchill at least for the poetic warning, Buchanan quotes the end of an article by Churchill published the day prior to the speech (October 4). Buchanan introduces it with "Yet Churchill could not contain his awe and envy at Hitler's audacity and nerve."

It is a crime to despair. We must learn to draw from misfortune the means of future strength. There must not be lacking in our leadership something of the spirit of that Austrian corporal who, when all had fallen into ruins about him, and when Germany seemed to have sunk for ever into chaos, did not hesitate to march forth against the vast array of victorious nations, and has already turned the tables so decisively upon them.

As with many quotes provided by Buchanan, there is much more in the context. The article as a whole is despairing over the secessions made to Hitler in the previous years. Churchill expressed concern over the leadership of Britain and France. The preceding paragraph to that quoted by Buchanan yields a much more complete perspective.

Much will depend upon the attitude of the British and French Parliaments, and upon the new measures which they may consider necessary for meeting the grave deterioration in their positions. It is, no doubt, heartbreaking to look back over the last few years and see the enormous resources of military and political strength which have been squandered through lack of leadership and clarity of purpose. There has never been a moment up to the present when a firm stand by France and Britain together with the many countries who recently looked to them would not have called a halt to the Nazi menace. At each stage, as each new breach of treaties was effected, timidity, lack of knowledge and foresight, have prevented the two peaceful Powers from marching in step. Thus we have the spectacle of a handful of men, who have a great nation in their grip, outfacing the enormously superior forces lately at the disposal of the Western democracies.

Churchill's "awe and envy," as Buchanan called it, was not for Hitler's "audacity and nerve," but for Hitler's resolve and leadership which Churchill saw as sorely lacking in the leaders of Britain and France.

Later, Buchanan incorrectly sums up that Churchill's alternative to the Munich Agreement was "rather than force the Czechs to give up the Sudetenland, Britain should to war." Buchanan then goes into reasons why Britain was in no place to put up a fight against Germany at the time. But Churchill was not pushing for war right then and there. His actual alternative can be found in the speech Buchanan quotes from October 5, 1938.

After the seizure of Austria in March we faced this problem in our Debates. I ventured to appeal to the Government to go a little further than the Prime Minister went, and to give a pledge that in conjunction with France and other Powers they would guarantee the security of Czechoslovakia while the Sudenten-Deutsch question was being examined either by a League of Nations Commission or some other impartial body, and I still believe that if that course had been followed events would not have fallen into this disastrous state.

Buchanan gives the impression that Churchill wanted to go to war in September, 1938. The truth is that Churchill wanted Britain, France, and the rest of the League of Nations to guarantee Czechoslovakia's independence six months prior while the League found a solution.

The 1930's were time in which Churchill has been credited for recognizing the dangers of Hitler and Nazism. Buchanan attempts to discredit Churchill by painting him as either weak, wrong, or absent during the key crises leading up to the Second World War. The truth is that Churchill was none of these. He was on the scene in each event and correctly foresaw Hitler's next moves.

Churchill, Winston S. The Gathering Storm. New York: Bantam Books, 1977.

Churchill, Winston S. Step By Step: 1936-1939. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1939.

James, Robert Rhodes, ed. Winston S. Churchill: His Complete Speeches 1897-1963, Volume IV, 1935-1942. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1974.

Manning, Scott. "Churchill's Earliest Warnings about Hitler." Digital Survivors. https://scottmanning.com/archives/churchillsearliestwarnings.php (accessed April 7, 2009).